All of us at some point, when asked by our friends, family or significant others to venture a new place, have uttered the words “What’s the parking situation like?” – But have you ever stopped to wonder why we ask that?

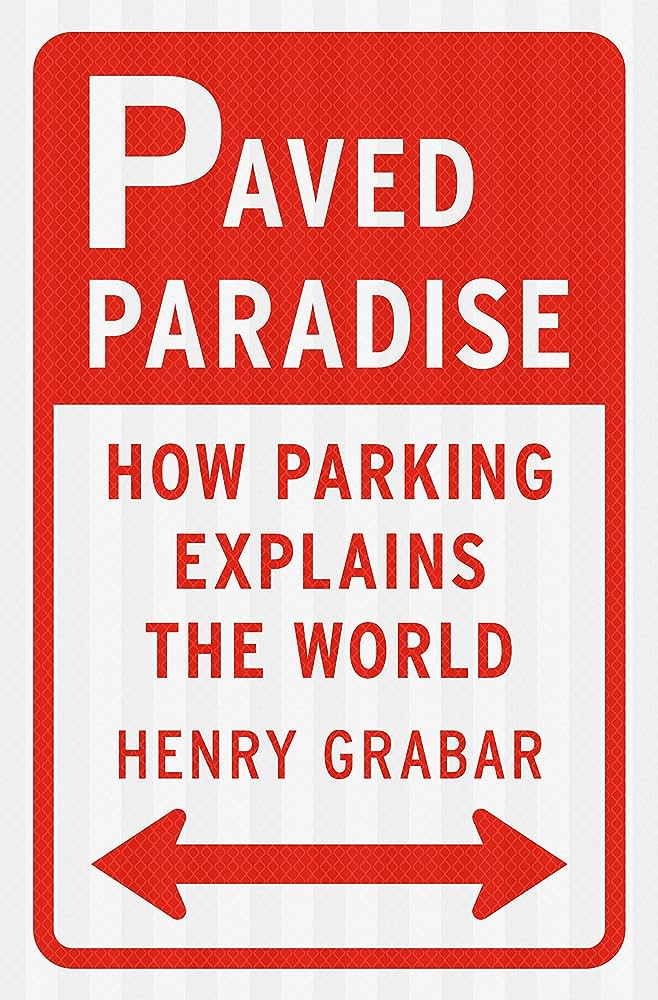

Tonight’s guest unlocks the secrets of how Parking has influenced our daily lives in a profound way, and chronicles them in his new book, Paved Paradise. Tonight we welcome writer and author Henry Grabar from Slate Magazine to Break/Fix to talk about how Parking, explains the world around us.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Spotlight

- Notes

- Transcript

- Highlights

- Learn More

Spotlight

Henry Grabar - Author & Journalist for Slate Magazine

Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World" is a timely, deeply researched, and persuasive account of how parking has bent cities towards its will, and what we can do to fight back. My review of this engaging book by Henry Grabar is out now in the Journal of Transport Geography.

Contact: Henry Grabar at Visit Online!![]()

![]()

Notes

- We like that you explicitly don’t blame the car or the drivers; but the architects; but also a plea for more mass transit – but wouldn’t that also be a shift? Bus depots and train stations would need more parking if they were more popular – more like the expansion of airports?

- We recently had David Page from Food Network on the show, he’s the creator of Diners/Drive-Ins/Dives; and we realized that one impact that wasn’t covered in the book was food’s impact on parking?

- What we particularly enjoyed was how you humanized parking through the characters, their stories and the impact – sometimes for worse, sometimes for the better to illustrate some truly illuminating facts!

- You talked alot about Solana Beach in CA; more extreme was Car Week in Monterey Bay / Carmel Valley – so many people descending on an area already hamstrung for parking – it was insane; how could we fix that?

- People often forget that parking for events isn’t always subject to the parking rules talked about in the book- lots of gouging and profit during events where parking is already stressed. Why should we pay $20 to park in a grass field?

- Thoughts on apps like Parking Panda, where you can reserve spots ahead of time? Is that better or worse? Park Mobile too?

- Parking in Europe is very different from the US; why?

- Can parking lots be made greener?

- What’s next for Henry Grabar, where do you take the conversation surrounding parking next? Do you have another book in the works? #spoilers

and much, much more!

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] BreakFix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autosphere, from wrench turners and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of petrolheads that wonder. How did they get that job? Or become that person?

The road to success is paved by all of us. Because everyone has a story.

Crew Chief Eric: All of us, at some point, when asked by our friends, family, or significant others to venture to a new place have uttered the words What’s the parking situation like? But have you ever stopped to wonder why we ask that? Tonight’s guest unlocks the secrets of how parking has influenced our daily lives in a profound way, and chronicles them in his new book, Paved Paradise.

We welcome writer and author Henry Grabar from Slate Magazine to Break Fix to talk about how parking Explains the world around us.

Henry Grabar: Happy to be here.

Crew Chief Eric: Joining me tonight as co hosts are [00:01:00] Don Wieberg from Garagetown Magazine and Tom Newman, who you might remember from the Randy Lanier episode earlier this year.

So, welcome. Thank you.

Tom Newman: Henry,

Crew Chief Eric: it’s great to meet you finally. Likewise.

Don Weberg: Hi, Henry, I’m Don.

Crew Chief Eric: Hi, Don. This is such a divisive topic. So many people actually wanted to be on this episode. They all have something to say about parking and it’s not lost on the non drivers either. Funny enough, just the other day, my daughters were arguing about how much parking they needed to add to their ever growing Lego city.

And that brings us right to Henry’s book. And not just a book, but a study. In parking. So Henry, tell us about the who, the what, the when, the where, the why of how this all came to be. What inspired the book and what pushed you over the edge to write it?

Henry Grabar: One of my inspirations was traveling around to American cities, going downtown and just seeing how much space had been dedicated to parking lots and garages and feeling like this is such a weird way to organize what is supposed to be the [00:02:00] economic center of this place.

Why is there so much? Low value land use concentrated at what’s supposed to be the most valuable place in the city. I think that’s a mystery that’s been with me for years now on a more specific answer would be to say that I work as a journalist and I write these stories about architecture and transportation and housing and at a certain point.

Parking just kept coming up in story after story. And that may not surprise your listeners. I’ve since obviously talked to many people who have affirmed for me that parking is at the heart of what they do and their work and their concern in their daily life and all that. At the time, I felt like, wow, this is a subject that’s absolutely everywhere.

And I felt like hadn’t really been explained in that way.

Crew Chief Eric: It continues to come up and I don’t think it’s ever not going to end. Even just the other day, I was watching an episode of the hit series 1923, which is part of the Yellowstone Trilogy. Harrison Ford makes a comment as he rolls into town. He’s like, where did the rails go for the horses?

And the guy goes, I had to put in space for parking. He goes, well, [00:03:00] where am I going to park my horse? It’s a story as old as time, but what’s interesting about that, taking us back to 1923, I feel that we’re at a point where history is repeating itself a hundred years later, going back to the 1920s. You make reference of this in the book where cities were changing, parking was taking over as it was expressed in that Yellowstone episode.

But nowadays we have to consider the change in the automotive landscape. Where are we going to park? All of these EVs, how are we going to make charging available to electric vehicles? We’ve reached 7 percent market saturation. They obviously that number is going to increase. They wanted to increase, but parking is extremely limited.

So now the ice powered cars are sort of like that horse that need to make space for the EVs. So you didn’t really cover that too much in paved parking, but I wanted to explore that idea with you.

Henry Grabar: It’s something that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. One of the leading indicators of whether somebody will buy an electric vehicle is whether they have reliable access to charging [00:04:00] for a lot of people.

That’s not a problem because they live in a detached single family home with its own garage. And so you can, at the very worst, just plug it in the wall, need slightly more reliability, maybe spend a little bit of money to install a level 2 charger or something like that. According to the American Community Survey, 1 in 3 American households do not have a private home garage.

And that means they either depend on some kind of multifamily parking situation, like a shared lot or garage, or they park on the street for either of those two groups. Transition to EVs is going to be really fraught because it’s not clear exactly how we’re going to be able to provide chargers at scale, especially for people who park on the street and.

Obviously, if meeting our climate goals depends on decarbonizing the automobile fleet, and that in turn depends on installing all these EV chargers, and that depends on sharing parking and being cooperative in how we think about street space and all that. Boy, I don’t know. It’s a tall order.

Tom Newman: One of the things that I think our [00:05:00] listeners would be really interested in is the origin of the garage.

A very sacred space to petrolheads and gearheads like myself and Eric and Don. I know it’s particularly important to Don. Can you talk a little bit about the origin of the garage and where that came from?

Henry Grabar: Rumor has it that Frank Lloyd Wright built the first. Enclosed domestic garage in Chicago and the Robey house and you can still go see that it’s a bulky concrete walled structure, which is typical of those early garages because they thought cars might explode.

And so you need to be protected. And they also had, you know, like, uh, trenches in the floors. You could get down and work under there and garages were originally at least as far as cars are concerned where spaces. To work on cars, they weren’t necessarily primarily intended to store cars, but to work on them.

That is the origin story of the garage. And it’s funny, even Wright recognized pretty early on, he started building carports instead of enclosed garages at a certain point. And I think he said, because he was afraid garages would fill up with stuff if he built them as part of the [00:06:00] house. And indeed that did end up happening.

Don Weberg: Henry, what you’re saying is spot on. I’ve heard this too. From my perspective, it came from the carriage house, but where we split here a little bit, the carriage house was obviously something more wealthier people had, and that was kind of where the transition came from. The wealthy person goes from having a horse drawn carriage to just a car.

But I’ve heard Henry’s story too, and I have heard that Frank Lloyd Wright was the first one to think, Hmm, where do we put a car?

Crew Chief Eric: Well, 1 of the things that stuck out in the book, there’s a whole set of chapters there where you talk about paid parking and metered parking and the advent of the meters and how that came to be in their history.

And it’s important to this discussion. And I think it plays into the conversation as well because I sort of gave it some thought. What wasn’t mentioned was. The transition from the mechanical meter to the electric meters and every electric paid parking meter that exists, whether now they’re park mobile enabled or otherwise means there’s electricity at that parking spot.

Granted might not be level three, 400 [00:07:00] watt might be one 20 might be two 20, whatever. That’s an opportunity for the parking capitalists to jump on that and say, let’s consolidate a parking meter and a charging station all in one.

Henry Grabar: I haven’t heard about the idea of parking meters. I like that idea a lot. I have heard from people saying potentially lampposts could be used like streetlights, obviously, are another source of power that’s coming into the street.

And those could be used potentially to install level one trickle chargers. The problem with that is. You have to have your car plugged in for a long, long time to get enough juice to drive 300 miles. The other issue is if you’re going to install something that’s a little higher touch, it’s going to provide more power.

It’s expensive. And I talked to the charging companies about this and they said, basically, it needs to be subsidized by cities. It doesn’t really pencil out for them to install chargers at the curb because they’re never going to make enough money. Charging people for that power to recoup the cost of installation and maintenance.

And the maintenance is a big issue here because these are public things. People will vandalize them. [00:08:00] People will drive into them. They’ll just break. There’s the weather, obviously. To have these things installed on the curb, they need to be subsidized. By the city or maybe by federal grants or something like that.

And then again, you’re looking at how much money are we going to spend to ensure that charging is electric. That’s a complicated political decision.

Crew Chief Eric: So then does it push it back to something you talked about in the book where now we have to relegate. EVs to a special parking lot or garage that has all the facilities and ability to charge those cars rapidly.

Henry Grabar: One potential future here is that charging technology gets fast enough that actually charging in the future comes to resemble filling up at the tank and you’re able to charge fast enough that it stops being such a concern. We don’t need to think about electrifying every single parking space. Another one that I heard is that building codes will actually contribute more chargers than the Infrastructure Act.

Will in terms of its commitment to charger installation, because a lot of progressive jurisdictions are now saying, if you’re building [00:09:00] parking, a certain amount of it needs to be electrified or needs to have the infrastructure in place to install electrification in the future. So the wires running under the concrete or whatever it is.

So people I’ve talked to have said pretty soon at the rate of new construction, it’s so much easier to build these things in new buildings than it is to install them in older buildings. Of course. Pretty soon new buildings are going to be contributing more EV chargers than retrofits.

Tom Newman: Or who knows, it could be like Mario Brothers.

We just drive over a strip in the road. Boom! Fully charged.

Crew Chief Eric: Don has actually talked about that before, where there’s some concepts, almost like mag chargers you have on your phone, you can drive over them. Even Rolls Royce, I believe, Don, developed something that would slide out underneath of the car?

Don Weberg: Yeah, it was Rolls Royce.

They have developed their electric car, but back in the day before they had one, they were feeling out their market and they were literally running around the world with this electric car showing their better customers the technology. You know, when asked, how do we charge it? They thought they were so slick because it was [00:10:00] literally a slab that goes in your garage floor and the car just rolls right over it.

The slab starts charging the battery. You’re done. You don’t plug anything in. You don’t touch anything. The car and the slab do everything for you. Well, it was considered very gimmicky and it was very cute and very cool. But of course, back then all the customers were still fairly older. People who didn’t really see a benefit or advantage to electric cars.

So Rolls Royce, they just shelved the whole idea. And now I understand it’s making a comeback because there’s a younger buying circle. That technology has been discussed in several municipalities about if you stop at a stoplight, you have a magnet there and that magnet senses all the cars. And when it hits a certain number, then it clicks over the lights.

Well, if we could do that with. Chargers, you would be charging your car while you sit at a red light. So red light to red light, you’re charging all these electric cars. It was pretty cool. But to Henry’s point, that requires a huge municipality investment, the city, the state, the [00:11:00] County, whatever, they’ve all got to get in on this, or they’ve got to start getting the people to vote in a bond to cover the whole thing.

Which again, it is a big political discussion.

Henry Grabar: I love hearing about that kind of technology. And again, that may not be ready to go to market right this second, but it feels like more evidence that the whole scene is evolving. And so we’re in this weird place where we are trying to obviously get the fleet to be electric as soon as possible.

But at the same time, we don’t want to commit billions of dollars to ripping up every city curb to install a technology that might be obsolete in 10 years.

Don Weberg: Exactly. That’s a big part of the problem too. Everybody’s worried about obsolescism. I mean, look at it, Tesla, arguably they were the first ones to market with a car that was acceptable as an electric vehicle while you’re still plugging them in, in your house, they haven’t adopted the drive over platform yet.

Why is that? It’s very interesting why Tesla has not gravitated to what Rolls Royce has been proposing. Why is that? I don’t know how [00:12:00] you feel about Tesla, but I’ve noticed it seems like what Tesla does. For the electric movement, the world follows it. Does every municipality want to invest in breaking up all the corners and installing these charges?

It’s a lot of work and a ton of money.

Crew Chief Eric: And why we’re talking about EVs first is because it’s top of mind for everybody. And again, parking is even more important in some ways. And all of this is evolving together. And one of the things I really liked about your book, Henry, is that you didn’t explicitly blame car owners, drivers, or otherwise, but the architects.

And it felt like there was a plea for more mass transit in there. When I boiled that down, it made me think a lot about How it parallels this discussion about EVs. There’s arguments to be made about how we’re displacing the carbon emissions. We’re moving it from the city centers back to the power stations by moving away from ice powered cars and people roaming around aimlessly looking for parking spots.

And then now we have these EV chargers and the coal power [00:13:00] plants are working harder than ever to power them. So it made me wonder. If we could switch to more mass transit, which the United States is so large, people oftentimes don’t really understand its grandeur as compared to Europe and Asia and other places that have more robust mass transit.

If we did ride more trains and buses, wouldn’t then we be offsetting the parking and forcing the bus depots and the train stations to have to accommodate more people that are driving to them to then use their services?

Henry Grabar: Yeah, I suppose that would happen. I mean, I think in places that do have higher rates of mass transit usage, carbon use per capita is lower full stop.

So yeah, there’s like some driving that needs to happen around those systems. But on the whole, it’s definitely a more sustainable way to get from A to B. There are pros and cons in the US context. I try not to make this book a call for mass transit investment, because I think unfortunately, in a lot of places in this country, The land use is simply not conducive to mass transit.

There’s never going to be a sufficient density in some of these places to [00:14:00] enable people to get to and from work reliably on an efficient mass transit system. That’s self sustaining or like moderately subsidized. There are places in this country, obviously where mass transit absolutely should be invested in where we definitely could be getting around without our cars.

But I think what’s appealing about parking as a subject is. Even if you live in a place that’s entirely car dependent, like one of the developers I talked to in my book is in Plano, Texas, north of Dallas. Totally car dependent environment, and even in a place like that, there is so much low hanging fruit in terms of the reforms that can be done around the way we treat parking to make a more pleasant and walkable environment.

Even if everybody has to drive there and drive away.

Tom Newman: After reading the first few parts of your book, I sat back and thought to myself, we are a horrible species. I mean, that is truly. And before any of our listeners think I’m crazy, you describe terrible things like fights and property damage and even murder inspired by parking disputes.[00:15:00]

Even small things like when we’ve walked out of a store, get in our car. and notice somebody waiting for the parking space that we are about to vacate, we might adjust the mirrors, fiddle with the radio, adjust a package on the seat, you know, whatever, knowing that the person who is waiting is growing increasingly frustrated and even angry.

And I think it’s fair to say that all of us have experienced the latter circumstances. And if you haven’t done that, I think you’re just a big fat liar. So what do you believe is the source of this sense of entitlement and ownership with public parking spaces when here in the United States, we’ve been taught that property is kind of a pinnacle of our society.

So why do we act this way when we don’t actually own the parking space?

Henry Grabar: That’s a million dollar question. I just want to say, you make a fair point about the opening chapters of the book. However, the narrative structure of the book [00:16:00] is sort of to set the stage with the problem and then emerge with some ideas for making it better.

So, the human race, or at least the American people, are not all bad in general terms and also in terms of their approach to parking. There’s definitely some reasons for optimism out there. With respect to our fixation on parking, part of it, and this gets back to the idea that this book is not supposed to hold drivers accountable for the parking situation, part of it is that we live in a society where we all have to drive to do.

anything. We have to drive our kids to school, we have to drive to the supermarket, we have to drive to go vote, we have to drive to work, we have to drive to the ball game, we have to drive to the park. That’s not our fault. The environment is constructed in a way that makes it impossible to do anything else and places in this country where driving is optional.

Are so scarce that they’ve become some of the most expensive real estate around. It actually is perversely a privilege to be able to live in a place where you’re able to walk, which is insane, but that’s sort of where we’ve ended up. And that goes back, I [00:17:00] think, to the fierce attachment we have for parking, because parking is literally the link between driving and whatever else you wanted to do in the first place.

And so I think, of course, people get attached to parking spaces. There are also circumstances in which parking is scarce. And in those situations, I think people also get. Territorial, right? Like if you go to a cold weather city where people shovel out public spots, there is a sense of ownership that creeps in and that happens everywhere.

Honestly, people park in front of their house. They often begin to think that space belongs to them just out of force of habit.

Tom Newman: I found that to be a particularly fascinating part of the book is the psyche. There was an academic that you referenced in the book that did a study that just to kind of paraphrase that said that.

When somebody drives to a certain place and they have to park, there has to be X amount of time between the destination and where they park. I thought that was just truly amazing because, you know, I had this conversation with my father and I’ll come back to that in a minute, but I think contributes one [00:18:00] to the ownership piece of it, and two.

This perception that there is never enough parking.

Henry Grabar: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. That’s a very important part of this, right, is that we have this expectation of parking, which is that we have very high expectations and particularly with respect to location. Now, I don’t think this is a fixed figure.

Actually, I don’t think there is some golden rule that says an American will only walk 200 feet from a parking space to get to where they’re going. If you look at a mall, for example, people will park at a mall. and they will walk five, six, seven, eight minutes to get from their parking space to a store inside the mall that is their actual destination.

That’s because malls are really nice to walk around in, and I think in cities that offer a pleasant pedestrian environment, you see that same kind of flexibility about parking. I’m from Manhattan. In Manhattan, when you’re driving someplace and you see an open parking spot, even if you’re five minutes away from where you’re going, you take it.

Because who knows what you might find when you actually get where you’re going. So I have this kind of [00:19:00] risk aversion. I like to park as soon as possible in case I don’t find another spot. Right. But obviously if you’re in an environment where the streets are pretty hostile to pedestrians, there’s no trees, there’s lots of cars going really fast, cutting in and out of driveways, well.

Then you probably do want to park directly in front of the restaurant. You came to eat at, and it’s probably not that interesting to you to park five blocks away and walk under the highway to get where you’re going.

Tom Newman: Can you talk a little bit about how parking has a direct impact on things like affordable housing?

And when I say affordable housing, I’m going to. borrow your explanation from the book, that’s not necessarily a home or an apartment that requires a lottery ticket from the city for you to become eligible to rent that property at a reasonable rate, but how parking in general just drives up the cost of housing, property values, taxes.

I don’t think a lot of people realize just how much parking affects what we keep in our pocket.

Henry Grabar: I don’t like to think too much about. Affordable housing, which is to say, like, [00:20:00] it’s actually subsidized by the government, requires a lottery ticket, et cetera. I prefer to think about naturally occurring affordable housing, which is to say, workforce housing that’s built by for profit developers, but at a low price point, doesn’t have a pool hall or a dog park on the roof or anything like that, but it’s just a place to live.

And for Okay. Most of the history of this country, those types of apartments have been the backbone of our housing infrastructure, and they have in recent decades disappeared. One of the reasons they have disappeared is that we’ve made it really, really challenging to build things, and one of the primary ways in which we’ve done that is to require all this parking with every project.

There’s just certain infill lots in cities where If you’re going to require every project to include two parking spaces with every unit, you are severely constraining the types of structures that can be built both geometrically and architecturally, but also financially, because building a spot in a structured parking garage to say nothing of underground is really, really expensive.

So even if you make [00:21:00] the project pencil, you find yourself entering this sort of cycle of escalating costs and rents. And I’ve talked to developers about this, and one of the things they say is, Once you’ve built all that parking in, you’re no longer at that bare bones tier of affordable rental unit.

You’re starting to add in perks and amenities, and then you say to yourself, Well, maybe actually this project ought to be targeted at a higher income level. And so then you install granite countertops, and then you install that dog park, and then there’s a Japanese rock garden in the back. And so, these things tend to build, and you get in this arms race, where everything’s getting nicer and more luxurious, and before you know it, you have very few people actually building the type of Basic work a day, but perfectly satisfactory housing that is so desperately needed.

Don Weberg: I’m from Los Angeles. You’re from Manhattan. Both of us are from big cities. And I think arguably Los Angeles is really the city that led the way they saw the cars, the future way back when. And so they started developing in that regard of, we have to create [00:22:00] spaces for all these cars that we’re going to park.

We have to create. Basis for people. We have to create roads that these cars can go down and not hit a horse on the way. You know, when you bring up the low income housing, it’s kind of interesting because when you go back to Los Angeles and you look at a lot of older, what used to be low income housing, even though they didn’t call it back then, it was just where the poor people lived.

The parking was basically the street. Because there weren’t very many cars and yet, isn’t it ironic that LA grew into this massive metroplex where you can’t get around without a car. I mean, you have got to have a car. Yeah, yeah, yeah. There’s a bus and whatever, but you had to have a car. So it was always interesting to me how those developers back then, how are we going to build something for lower income people yet still accommodate the car?

And like you say, well, the minute you start accommodating the car, well, God, they’ve got a car. They must have some disposable income. So yeah, let’s. Put a rock garden, let’s make it a little nicer. Seems to be more of the human DNA. We want better, better, better, better, better. We want [00:23:00] to aspire to build the best, to be the best, et cetera.

And I think even for our poor people, if you’ll just forgive that term for a minute, we want them to be the best poor people in the world. We have granite countertops. We have electric vehicles for our poor people, if that makes any sense. It is interesting to listen to you talk about how one pulls at the other, which pulls back.

It’s a very interesting pendulum.

Henry Grabar: This is a longstanding debate in the regulation of housing in the United States, right? Like you can go back to the late 19th century, early 20th century, progressive reformers visiting tenement buildings and saying these conditions are unacceptable and every bedroom needs a window.

And every apartment needs a fire escape, those kinds of regulations. I think today we would all basically say, yeah, that should be a basic condition of having an apartment in this country. We don’t want people building windowless apartments just because we have a housing shortage. And I can think you could see parking on that spectrum to the original desire with the zoning for parking.

Was not to entirely eliminate the [00:24:00] construction of apartments, although some people later used zoning for parking to accomplish that goal, but it was really to ensure that we solve the spillover parking problem on the street. There are unintended consequences to putting requirements on the creation of housing.

You have to make choices. And I think if you’re interested in an automobile society, everybody drives everywhere. And you could certainly make the argument that it would be great if everybody had a parking spot at their house. But I think one thing we’ve realized over the last few decades is that that requirement, however, noble in name, and I don’t even think it was that noble in name, but that’s another conversation.

It has severe externalities in terms of the look of the architecture, the cost of the housing, the walkability of the neighborhoods, like there’s all kinds of negative effects that go along with that.

Don Weberg: I live now in Dallas. I’m getting all this news from all over the place. And it’s the darndest thing.

We’ve got one developer here in Dallas and he’s huge. He literally gone from homeless. To he’s almost a billionaire. So obviously property and parking minimums is a huge part of the conversation. Now, when I moved here, I thought the [00:25:00] last thing in the world I was ever going to hear about again, we’re parking minimums.

Maybe in Houston, you’d hear about this, but everywhere else in Texas. Are you kidding me? We have more land than we know what to do with out here. So I don’t think anybody, nope. Nope, there’s a lot of cities out there who want to be sophisticated and big city and have parking minimums. Well, of course, all the businesses are up in arms over this because all that does is curtail business.

So it’s interesting in a conversation with him, he told me about Fayetteville, Arkansas. And in Fayetteville, he sent me a video, real nice video that this guy put together. And it was how the entrepreneurs, the business owners, etc. got together and essentially ganged up. On City Hall and said, we want these gone.

Well, of course, City Hall said, well, where’s everyone going to park? Have to have our parking? No, no, no, no, no. Get rid of them. And this is what’s going to happen. You’re going to see success downtown. You’re going to see revitalization. They had buildings in Fayetteville that Hadn’t been used in 30 years because they [00:26:00] didn’t meet the parking minimums.

It was really kind of crazy instead of being grandfathered in where, okay, this building was built during the civil war. It has five parking spaces, but it can service, you know, 300 people in a day. The city said, no, we got to shut that down until you can build parking minimums.

Henry Grabar: I talked to a bunch of architects who described the situation with historic buildings in particular as the parking padlock.

You may not be able to see it, but like across the front door, these old buildings is a parking padlock. Unless you provide enough parking, you can’t unlock the door and do something with the building that still affects structures today. But if you go back and you rewind 70 years of our urban history, how many buildings have we lost?

To this requirement, how many formerly walkable, formerly dense neighborhoods full of like great old loft buildings with 14 foot ceilings have been torn down to satisfy this requirement.

Don Weberg: Back in Los Angeles, we had a restaurant tour. He had a beautiful, beautiful building at the corner first in [00:27:00] Maine. I mean, how do you forget that?

And it was derelict. Well, why can’t we use it? parking. There’s no parking for it. Okay. So if I buy this building and turn it into a restaurant, let’s say, what do I have to do? Well, you have to provide all this parking. Essentially what it meant was, you know, here’s the block and here’s the little piece of property with the building.

Our guy had to buy basically this whole three quarters of a block, leaving whatever businesses are leading up to his building. So he had to buy all the houses. Tear him down, pave it, and turn it into a parking lot for his now restaurant. Is this still there? Did it happen? Did he tear down the block? He tore down the block.

First in Maine, it’s a place called Original Mike’s. You can look it up on the internet. And yes, Big Mike, as is known, he’s six foot eight. He bought every single house one by one by one. He literally had to go door to door, make offers to all these people.

Henry Grabar: That was insane.

Don Weberg: And all the people accepted because they were good offers.

So he bought the entire block. And then, of course, the city realizing, hey. We’ve got a nutcase on our hand. What can we built him for [00:28:00] now? The whole point was he hadn’t even set foot in that building yet that he wanted to turn into a restaurant slash nightclub. He hadn’t even touched that thing yet because he wasn’t sure he was going to be able to.

He had to secure all those houses, you know? So yeah, the restaurant is still there. He no longer owns it, but it is still there. It’s very popular. So Fayetteville takes a chance. They get rid of the parking minimums. And the next thing you know, that Civil War building gets leased by a company who wants to open a wine bar restaurant situation.

It is the cutest thing on the face of the planet. And people are parking blocks away because they want to go to this experience. They want to go see the wine cellar. They want to go eat the food. They want to do this. Well, of course, next door you got a shop. Next door you got this. The next thing you know, Fayetteville, Arkansas is lifting all of its parking restriction.

Now, it’s been an incredible transformation. To lift these, and it kind of goes with what you’re saying, let’s build a nice little area where people will walk five to ten minutes to get to their destination. Well, why are they doing that? Because it’s a nice [00:29:00] area.

Henry Grabar: It’s exactly what you say with Fayetteville, right?

The distance people are willing to walk is fungible. It does fluctuate. Based on the quality of the urban environment. And if you create an environment, that’s exclusively parking lots, you are going to create the expectation of easy parking. And it’s a negative cycle in that sense.

Don Weberg: I kind of blame Los Angeles for it in a way I go right back to it.

And that was the city of the future. They were the ones who embraced the car and they realized this is the future. We have to welcome the cars. Part of how they did it was. You have an avenue, and on either side of the avenue you have shops and restaurants, and what they did was they built alleyways behind them, and behind that were parking lots.

And that, for Los Angeles at least, that’s where the parking minimums started, was they realized, oh my gosh, we’ve got all these businesses entertaining all these people, they’re bringing their cars, they’re not able to park them, so now we have to impose these parking minimums on them. It was an understandable decision by the city, but at the same token it’s a double edged sword because it drove business away.

Crew Chief Eric: Don has [00:30:00] inadvertently reached back to another episode that we did where we had David Page from Food Network on, and we talked about his new book Food Americana and the influence that food has had on the automotive industry. Sort of the undertone here is, especially in these city centers where they’re trying to change things over and even the urban and suburban areas.

A lot of these decisions revolve around food and our ability to get it, whether we’re getting it, take out, dine in or grocery stores, people need to eat. We need our own personal fuel. And so it’s really funny how we don’t talk about it. It’s almost like food is sacred in this sense where we don’t recognize how it even influences this discussion about parking.

Henry Grabar: Yeah, I think that’s true. I think restaurants have suffered the most from this policy. We talked a lot about housing is obviously more important in a fundamental way to our society than restaurants are. But the thing about restaurants is that the requirements for restaurants are super, super high. And a lot of cities, it’s one space for every 100 square feet of interior [00:31:00] space and a parking space with an ingress and egress is about 300 square feet.

Maybe 250. So you’re talking just at a basic level, 2 to 3 times as much real estate devoted to parking as to restaurant, 100 square feet, a restaurant, 250, 300 square feet of parking. And so, yeah, you do end up by requiring. A kind of land use that is mostly parking and I think you look at a fast food restaurant in the suburban strip mall and that is kind of corporate architecture that comes from standards that have been established by Chick fil a or Taco Bell or whoever it is.

That’s also very much in tune and a form that has evolved with those local parking requirements that say that for every parking. Number of stools at the counter or whatever. You need this many parking spots.

Tom Newman: That’s an interesting point too, because you’re talking about the size square footage of the parking space.

While absolutely pertinent to food in restaurants and so forth and so on, I was really struck by that same [00:32:00] kind of logic being applied to housing in terms of, okay, you’re building an apartment complex or a townhouse unit or set of units, maybe there’s 10. Because of zoning laws or somebody’s arbitrary decision for these 10 units, we now suddenly need 40 parking spaces.

And I know that’s a little bit hyperbolic, but based on the research that you’ve done and what I’ve read, it doesn’t quite seem that far fetched.

Henry Grabar: I got my attention drawn recently to a project in Venice, California, where the project was opening on an old public parking lot. And so in addition to all the parking spaces required for the units, They had to rebuild all the spaces in the parking lot, and that can really push your parking ratios really high.

And I think, again, it makes sense intuitively to a lot of people. They say, you’re building something in a dense neighborhood, you have to provide parking, because otherwise it won’t be enough. I think what those people don’t realize is, in addition to the fact that, obviously, more parking creates more car ownership, which creates more traffic, [00:33:00] you’re building yourself into a big congestion problem, but there’s also the fact that Parking is so expensive to build.

And this is one of the things that shocked me most when I started working on this book, because you think of parking as being the land use of last resort, the thing that happens when the building’s been torn down and there’s nothing else that anybody wants to do with it. But the average cost of a stall in a structured garage in 2023 was 28, 000 nationally in LA, it’s much higher.

Underground, it’s much higher. Think about that. At the typical fee that people are willing to pay for parking, it takes so long to make a 28, 000 parking space pay off if it ever pays off, considering the cost of maintenance and depreciation and all that. So it’s a real difficult situation.

Tom Newman: I shared a story that kind of illustrates this challenge, if you will.

I hesitate to call it problem because I’m sure that there are people that are smarter than me that, you know, have quote unquote planned ahead, but still, it just kind of seems a little bit off. A couple months ago, [00:34:00] unfortunately, my mother wound up being diagnosed with a condition that had her in the hospital.

Prior to that, I was over at my parents house, and we were talking about what books we’re reading. And I looked at my dad, and I said, you need to read this book, Pave Paradise. And he said, what? Parking? Are you kidding me? And I said, well, let me ask you a fundamental question. Is parking a problem? And he goes, oh, yeah.

There is never enough parking, and kind of what Eric alluded to at the beginning of the show, whenever we set out, the first question a lot of people ask is, what’s the parking situation? Like I said, he was convinced that there’s never enough parking. Mom has her procedure. She has to be admitted overnight.

I happened to look out the window of her hospital room and it overlooked the parking lot. My eyes kind of got a little wide there for a second because perspective is everything, right? And I said, hey, Pop, come here and take a look at this. You know, he looked up and he goes, yeah. And I said, do you remember that conversation we had about never enough parking?

Probably the first third of the hospital parking lot. [00:35:00] Was packed, not an empty space anywhere. But then you looked out beyond and the remaining 60 to 70%, you know, whatever was just a sea of empty asphalt. And I said, do you still think we have a parking problem? His jaw literally hit the floor. You know, when we talk about the problem with parking is it’s a perception issue, right?

We have an excess of parking that nobody wants to use. It’s all about the parking we want,

Henry Grabar: right? That’s an opportunity to talk about. I think 1 of the most. Counterintuitive ideas in the book, which is the idea that paying for parking creates more parking spaces. And what you describe in that hospital parking lot is often true on a local Main Street where the very best spots will be taken first thing in the morning by people who more often than not work at the businesses or the offices on that block.

And they will [00:36:00] park there at 7 30 or 8 in the morning and they will park there all day. And so people will arrive at midday and they’ll say, there’s no parking available here. They’ll be correct that there is no parking directly in front of the place they want to go. But often that available parking is just one block, two blocks away.

And what’s happening here is that it’s sort of poorly organized. If you charge even a little bit for those prime parking spots, those all day parkers will find that over the course of 12 hours. You know, that dollar an hour starts to add up, especially if they’re parking there every day. And so they’ll park two blocks away, and that means that when you show up for lunch, you’ll have a spot directly in front of the restaurant that’s available to you, and it will cost you one, two, three dollars, something like that.

And for the people who park further away, maybe it’s free parking, maybe it’s cheaper parking, but in any case, the walk that they make to and from work, to and from their car, Is amortized over the course of that 12 hour workday. I think that’s an important thing to think about walking distance as well.

Nobody wants to walk 10 minutes to spend 30 seconds in a store picking up [00:37:00] their dry cleaning. But if you’re working for 12 hours and 10 minute walk isn’t so bad.

Don Weberg: What you 2 have brought up here. It kind of sounds like the segue to where cities start to slide back into that parking minimums.

Conversation because you’re bringing up people who they arrive at 7730 in the morning, they get the prime space in front of their work. The car sits there all day. And then they come out, they go home because they leave their car there all day. But other people are arriving. They got to park 23 blocks away.

I think this is where city council, etc. Start to wake up and say, Hey. We need parking minimums. And I wonder, do you see that too? Am I on the right track? I think

Henry Grabar: that’s, I think that’s the history of parking minimums in a nutshell is you have these overcrowded city blocks, merchants fearful that their customers are going to leave and go to a suburban shopping mall and parking minimums are the result to try and constrain new businesses from opening and putting more pressure on the parking picture.

There is obviously another way, right? I mean, the other way is. charging for that parking. There’s often this fear, if we charge for our [00:38:00] parking, no one will come here anymore. If that’s true, you have bigger problems. If the whole attraction potential of your central business district, your retail strip, if what you’re offering is only good enough for free parking, if it’s not worth a dollar an hour to someone who’s driving down there, then frankly, it’s obviously just not that good.

I’m not trying to be mean, but this gets borne out when you start charging for parking. People continue to come, they continue to patronize the restaurants and shops, they find the parking situation is easier than it was before, and that’s worth something to them, right? Because there is a cost of free parking, and it’s time.

It’s the time you spend getting to the main street, finding there’s no available parking, circling the block, etc., etc. You know, Don Shoup, who’s the godfather of parking studies, would say, you should price the parking. So that there’s always an available space on every block and if that price is so high that nobody drives there anymore.

Well, then you lower the price. I mean, that’s kind of the magic of parking meters is that it is a [00:39:00] wonderfully flexible policy as opposed to, for example, tearing down a row of houses to build a parking lot. That is hard to reverse.

Tom Newman: Yeah, and that’s a fantastic thing, and I’m going to give a quick shout out to my friend Mike Carr.

He’s actually a land use attorney, and when I told him about this podcast that we were going to do, he was very enthusiastic because he deals with it. He described a brewpub investment company that purchased an industrial area, a former plant of some kind just north of Philadelphia. And they turned it into this brew pub, shops, so forth and so on, made a parking lot based on the usable space that they own.

The township that it resides in, they basically told the owners that you don’t have enough parking. They said, what are you talking about? We have enough parking. Our lot’s never full, but we’re profitable. We’re doing well. And they said, well, you know, maybe if you installed meters, we could share the profits and increase the parking that will attract more people to you.

And they [00:40:00] said, no, I think we’re good, but you could do it if you cut down the trees. And their response was, we like the trees. And basically told them to go pound sand. And they won. I

Crew Chief Eric: don’t know that some of the studies really capture the end user, what all of us may be thinking. Some of it is reactionary.

Some of it is, based on behaviors that have been observed. But in this conversation, I begin to think about how I choose my parking. There’s often times where I want to pay more for a particular type of parking. So I’ll give you a prime example. I hate driving in the district of Columbia. So I will take any Metro and station because I can park there all day for five bucks.

And when I’m in the city, I don’t need my car anyway, but because I’m a car guy. I’m more worried about my car and what state it’s going to be in when I get back and, you know, not having to drive through potholed, ridden streets of DC. And the same is true at the airport. I pay more for covered parking because I don’t want my car out in the elements.

When I come home from a trip as a car enthusiast, I think about parking in [00:41:00] a totally different way. That whole situation is yes. What is the parking situation? But what’s that premium parking that I’m going to get? Not because I’m trying to show off, but because I’m trying to protect my personal investment.

So there’s a lot of other factors here. And I think that plays in maybe to the discussion and it’s sometimes overlooked.

Henry Grabar: Yeah. I think also we should acknowledge too, that there is a gender element at play here too. I’ve talked to women drivers who will say they also will value a premium parking space because they don’t want to walk 15 minutes through an urban street at night or through like a sketchy ass parking garage or something like that.

So like, that’s another group. I mean, it’s kind of another question about whether this is fair or not, but let’s just say there is definitely a market out there of people who would like to be able to ensure that they’re going to have a great and safe parking spot that’s close to where they’re going.

Crew Chief Eric: And I think that’s where the mobile apps come into play. And my wife has brought up more than once an app called parking Panda, which was not referenced in the book. You get references to park mobile and some other apps like that, where you can [00:42:00] do metering digitally and things, but parking Panda is actually a reservation.

System. So think about that. You’re a single female. You don’t want to walk through that parking lot at night, but you could reserve a spot at a certain time near a store. So you’re closer. I think that parking Panda, that more concierge white glove approach to parking is really interesting. I ask her frequently how it really works and she says it works great.

I’ve always gotten the spot that I reserved. There’s nobody else sitting in it and things like that. And so something else to look at. There’s a lot of technology now that can help the parking situation.

Henry Grabar: Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. One of the things I’ve been wondering about lately is like. What if we thought about parking meters away?

We think about tolls. Now there’s a lot of places where you drive around New York and you get told automatically via license plate recognition

Crew Chief Eric: or easy pass.

Henry Grabar: Yeah. Or easy pass. But like now you don’t even need easy pass. They’ll just take a photo of your license plate and send you a bill in the mail.

It’s made this process very seamless and people generally no longer think about it. Like. Oh, I’m about to pay again for this service. It’s just become kind of a [00:43:00] fixed item on your monthly budget. Oh, you got to account for insurance, registration, tolls, etc. One of the advantages of doing this with parking would be you could get rid of this whole.

Rigmarole we go through with the parking meters and the fines, like there’s really no need for anybody to be fined for overstaying a meter and there’s no need for anybody also to have to pay more money than they need to pay if they leave a spot early. That whole system is so primitive and it doesn’t need to exist anymore because we have cars.

The drive around and read license plates and could just say, you were foreseen in this spot at this hour, you were no longer in the spot at this hour and you get billed according to that. And that’s that.

Crew Chief Eric: Same is true now at a lot of airports, they have those scanners that look down to see if a car is sitting in the spot.

Not only does it help you find an available spot quickly, but that technology can be used to say, okay, that car was there at that moment and no longer there to be super accurate, because even when somebody is coming by on a little scooter or something like that and taking those pictures. That’s based on a cycle, right?

How many times are they going by in an [00:44:00] hour or whatever it is? So the accuracy is better than, okay, I put in a quarter in the meter and I only use 10 cents worth of that quarter, that sort of thing. So Henry, in the book, you talked a lot about Solana beach, which is a very particular area in California.

Lots of things going on there with respect to parking and housing and architecture and things like that. But I thought it was funny. That this past summer, Don and I experienced what could be considered parking hell in a way, especially for car enthusiasts, bigger than the Solana beach problem encapsulated in 10 days is car week, which happens in the Carmel Monterey area.

And not only is parking stressed in that area in general, now you have car enthusiasts with multiple cars and trucks, and they’re going to pebble beach and the quail and all these shows and all this. Extra is descending upon that area and it takes an already stressed parking situation and makes it tenfold.

So I wonder if Car Week, Carmel, Carmel Valley, Monterey could be used in maybe a future study to look at how they [00:45:00] handle that situation because Car Week has been around for many, many years and it’s not going away anytime soon.

Henry Grabar: I mean, Car Week is a particularly funny example because it’s like a very vivid illustration of the old axiom, you’re not in traffic, you are traffic.

You’re not having trouble finding parking, you are creating a parking shortage. It’s tough because I think for a lot of big events, the obvious answer is cars have never been good at getting a lot of people to one place at one time because of simple geometric constraints. But obviously if driving is a precondition, that’s definitely a tough one, but it would be a fun experiment to run, right?

Like you got a lot of, a lot of people who think about this stuff like you guys do, surely they could come up with a system or an experiment or something like that to figure out the parking situation. Of course, a lot of the time, what you have in those situations, you get all of a sudden a very vibrant black market for parking spaces.

You go to like, uh, near a college football stadium or like near Churchill downs on the day of the Kentucky Derby,

Tom Newman: Indianapolis 500.

Henry Grabar: Yeah. Like, you know, 25 bucks to park in my driveway for a [00:46:00] couple of hours. Yeah.

Crew Chief Eric: Or 25 bucks to park in the grass. Like that’s not even a parking spot, right? It’s not officially sanctioned.

Everything’s

Henry Grabar: a parking spot, uh, on the day of the big game.

Crew Chief Eric: In our last segment here, let’s talk about. Us versus them. That’s the U. S. versus other parts of the world, especially Europe and Asia, which are also car dense as well. You spent some time in Europe this summer, so did I, and I noticed a stark contrast in the way Europe handles its parking situation versus the U.

S. Obviously, they are more compressed, we have a lot more land, but I don’t see oceans of asphalt. A lot of times, cars are Hidden from plain sight in these underground garages or garages are built into buildings. They’re integrated. Denmark has a big policy of no single use buildings. So every building they construct has to have a multifaceted approach to it and can be used for something in the future if it is abandoned.

So I wanted to talk about some of the differences there between Paris, Copenhagen, even Montreal, you know, Canada handles [00:47:00] things differently than we do. And some of your thoughts on what you’ve seen in your travels.

Henry Grabar: Yeah, let’s just get one thing out of the way right off the bat. The car ownership rate in Europe, and especially in Canada, is not that much lower than it is in the United States, especially Western Europe.

It’s easy to look at some of these European cities and just say, well, that’s Just a totally different paradigm. We’re never going to be like that, et cetera. And there are definitely fundamental differences, but these remain societies where lots and lots of people drive. And I think one of the fundamental changes that they’ve made that distinguish their urban environments from ours is to think about parking in a different way.

One thing I noticed in a lot of European cities and in particularly smaller cities and even towns is that they have what they would call a park once strategy. The idea is instead of an American city where like every sandwich shop and dentist office and movie theater is required to have its own parking lot, a lot of European cities will have a public parking garage, paid parking usually, that’s sort of on the edge of town or maybe even at the center of town, but they’ll have a few of them and there’ll be [00:48:00] really big signs when you drive into the city that will say, here’s where to park.

Here’s how many spaces are left. And you’ll go there and you’ll park, and then you will spend several hours on foot. You will go from store to store, to restaurant, to movie theater, or see a play, see a concert, or whatever. And then when you’re done, you’ll go back and find your way to your car and leave town.

But that is a way to ensure that there may still be lots of people that are driving to and from the city, but they’re not driving to and from the various establishments inside the city. And that permits that parking to be shared between all the uses in the city, and also sort of kept off the main drag and out of sight.

Crew Chief Eric: And Don and I commiserated over an experience that we shared, but separately in Venice, where you’re not allowed to be in the ancient city of Venice. You have to park in Padova and take the train in and everything is walkable. There are no cars allowed in Venice. You either do everything by boat. Gondola, and then you have the option of bike, scooter, Vespa, all that kind of stuff.

And Italian cities, Venice is not alone in that sense. Florence is very similar. You park on the outskirts of the city and you [00:49:00] walk into the city. Granted, they got to make deliveries and sometimes they have special exceptions for things like that, but they try to push the cars out of the cities and make them more walkable.

Now, you were just back from Paris, totally different situation there.

Henry Grabar: Yeah, Paris is really interesting. First of all, it’s a big city, right? We’re talking a metro area of 10 million people. So it’s not some little, no offense to Venice, but like it is a different scale. They’ve decided basically that if you’re going to drive a car in Paris, you need to have a garage to park it in.

They’re really trying to cut down on street parking and people who use street parking. The idea now is that’s for deliveries, that’s for ambulances, that’s for pickup and drop off and taxis. It’s not for long term car storage, long term car storage has to happen off the street because that street space is too valuable in a city.

That’s as dense as Paris is in the last couple of years, they’ve converted all these free parking spaces to all kinds of new uses. And my favorite, one of these is they’ll take blocks in front of schools and turn them into play streets. And this has happened all over the city, but like, they’ll just get rid of the cars and the [00:50:00] blocks in front of the schools and on these blocks, they used to have these big fences along the sidewalks.

To prevent the kids from playing and wandering into traffic and getting hit by a car. And since they closed the blocks of traffic and got rid of the parking spaces, they’ve been able to tear down those fences. And so you end up with this much more open and pleasant environment. And it’s pretty low touch, right?

It’s not like they’ve done a ton of work, spent a ton of money. Just the presence of these kids coming in and out of school all day creates a kind of automatic social life in the street. There’s soccer games, there’s hopscotch, there’s kids on scooters, bikes, parents picking up, dropping off their kids, and then other people from the neighborhood too who will just come and they’ll take that block if they’re bringing their cart to or from the market because it’s easier than walking on some narrow sidewalk and cafe terraces spreading out because it’s quieter because you don’t have the motorcycles going by, etc.

All that’s possible when you begin to look again at Parking spaces.

Crew Chief Eric: If we go over to Asia, we talk about Tokyo and other parts of Japan. As an example, they actually feed the size of the vehicles accordingly, and they [00:51:00] have minimums and things like that, where even the width of the car is important because that also dictates how many cars they can fit.

In a parking area versus some of the larger vehicles we have in the States. This is why they don’t have things like a Yukon or a Tahoe or an expedition or something like that. It just wouldn’t physically fit in places that you could park, let’s say in downtown Tokyo. So they have a whole different approach that it affects the automobile industry in such a way that they have to physically make the car smaller.

And I think that’s really interesting too. So Henry, how can we make parking lots greener? There’s these oceans of asphalt out there and we see them being overutilized and sometimes underutilized. Like paddocks at a racetrack are completely empty if nobody’s there for a race, right? And so it makes me wonder, especially in thinking about conversations about us versus them and how Europe does things differently, why aren’t we seeing more solar panels?

Going up to provide shade for vehicles, keeping them cooler. That way we don’t have to run ACs as hard, which is a positive thing for the [00:52:00] environment as well. And I bring it up because I’ve only noticed it in one place in the United States and it has a European influence. And that’s at Ikea where they provide the shaded solar paneled areas that you can park under.

So what are your thoughts on making parking lots greener in the future?

Henry Grabar: The economics are just not in favor of building those solar panels over parking lots, which is unfortunate, but I agree. It’s a great place for them. France actually has a law now that parking lots over a certain size, I think, have to be half covered in solar panels.

So a city or state could do that and decide to try that out. I think it’d be pretty interesting to see what happened. The other thing about parking lots and making them greener is obviously the impervious surface. One of the issues we see every summer in the United States is these increasingly intense rainstorms that Overwhelm our sewer system and flood businesses, basements, people’s houses, et cetera.

One of the ways we can deal with that is to try and address all this concrete and asphalt that makes up our cities. Parking lots are not the only or even the primary source of impervious surface. That’s probably [00:53:00] buildings. But the buildings are challenging to work with and parking lots are right there.

What could we do to make, maintain their parking function, but transform them so that they permitted water to go into the ground and replenish our aquifers instead of running right into our sewer systems. And I think that’s a big challenge, but it’s not a very difficult one. Somebody’s going to figure out a way to do that.

And we ought to make it obligatory for new parking lots to conform to those rules.

Crew Chief Eric: What’s next for Henry Grabar? Where do you take this parking conversation next? Do you have another book in the works? Any spoilers you can share?

Henry Grabar: So far I’m on a, uh, parking policy road show. I’ve got a couple trips scheduled to Orlando, to Denver, Santa Fe, Boston.

Gonna be talking parking. More broadly, I’m a Loeb Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. And so I’m taking classes and taking a break from writing and trying to learn some stuff.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, Henry, we’ve reached that part of the episode where I get to ask you any shoutouts, promotions, or anything else you’d like to share that we haven’t covered thus far.

Henry Grabar: This was a really thorough conversation. Gotta [00:54:00] give a shout out to Don Shoup, the Godfather of Parking Studies. His book, The High Cost of Free Parking, is the Bible of parking. It’s a big book. It’s not for everybody, but it is the Bible. And also to the Parking Reform Network, which is A really interesting group of local activists who are trying to change parking laws for all the reasons we’ve just discussed.

So if you’re interested in this that might be a good place to get started

Don Weberg: Everyone that says life is all about the journey and not the destination has obviously never had to search for parking To learn more be sure to check out henry’s new book paved paradise available on amazon and audible Depending on your reading style.

You can reach out to henry at henry dot grab bar at slate dot com, or follow him on social media via linkedin.

Tom Newman: Henry, I could talk to you for hours on this, and I know that sounds kind of geeky, but that’s just the hard truth of it. Candidly, I never really considered or even thought about how parking can be so impactful, [00:55:00] not just within car culture, but across many different echelons of everyone’s life, not just the people who own cars.

Crew Chief Eric: Henry, I can’t thank you enough for coming on Brake Fix and sharing this extremely interesting study on one thing that I think all of us, whether you’re a car enthusiast, motorsports enthusiast, just a person in general, have a vested interest in, which is parking. And I don’t think any of us have really…

Sat down and thought about how much it affects our lives in a profound way. And I think I can speak for my co hosts in this. We appreciate you bringing this to light, bringing this to the surface and making us take a deeper look, internalizing what parking really means to all of us.

Henry Grabar: Well, I, uh, I really appreciate you all giving us such a close read.

So fun to talk to people about this subject and especially to people who have been thinking for so long about cars and how they work. Thank you so much, Henry. Oh, this was so fun. Anytime.

Don Weberg: Good to meet you, Henry

Paradise

Pink. A [00:56:00] and a hot

that you, you.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP [00:57:00] goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gumby bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Introduction to BreakFix Podcast

- 00:39 Meet Henry Grabar: Author of Paved Paradise

- 01:45 The Inspiration Behind Paved Paradise

- 03:25 The Future of Parking and Electric Vehicles

- 04:58 The Origin of the Garage

- 06:27 The Evolution of Parking Meters

- 19:21 Parking and Affordable Housing

- 28:16 Fayetteville’s Transformation: From Parking Minimums to Vibrant Community

- 29:15 The Origins of Parking Minimums: A Look at Los Angeles

- 29:58 Food and Parking: An Unexpected Connection

- 30:41 The High Cost of Parking Requirements for Restaurants

- 32:53 The Real Cost of Parking: Financial and Spatial Implications

- 33:58 Personal Stories: Parking Perceptions and Realities

- 35:36 The Case for Paid Parking: Efficiency and Availability

- 37:35 Parking Minimums: History and Impact on Urban Development

- 41:48 Innovative Parking Solutions: Technology and Policy

- 46:12 Global Perspectives: How Other Countries Handle Parking

- 51:29 Making Parking Lots Greener: Challenges and Opportunities

- 53:23 Conclusion: The Future of Parking and Final Thoughts

Learn More

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others by way of Break/Fix and GTM. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

|  |  |

There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.

Everyone that says life is all about the journey, and not the destination, has obviously never had to search for parking. To learn more, be sure to check out Henry’s new book “Paved Paradise” available on Amazon and Audible depending on your reading style. You can reach out to Henry at henry.grabar@slate.com or follow him on social media via LinkedIn.

Want to learn more?

Henry Grabar is a staff writer at Slate who writes about housing, transportation, and urban policy. He has contributed to The Atlantic, The Guardian, and The Wall Street Journal, and was the editor of the book The Future of Transportation. He received the Richard Rogers Fellowship from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and was a finalist for the Livingston Award for excellence in national reporting by journalists under thirty-five.

Don’t forget to pick up a copy of Paved Paradise at your local book store or on Amazon today!

Recommended Reads

- Reading List

- Goodreads

Reading List

Goodreads

Guest Co-Host: Don Weberg

In case you missed it... be sure to check out the Break/Fix episode with our co-host. |  |  |