Hannah Thompson examines the history of the NASCAR Hall of Fame from its inception in 2001 through the global pandemic, bringing into consideration why Charlotte was selected as the seat for the Hall and how the Hall has affected NASCAR and its fans. Charlotte is often overlooked in motorsports history despite its lasting impact on the auto racing world.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Bio

- Notes

- Transcript

- Livestream

- Learn More

Bio

Hannah Thompson is a cultural historian of the Carolina Piedmont and is new in the museum field with her current position with the Gaston County Museum of Art & History. Ms. Thompson also helps restore Coca-Cola “ghost signs” throughout the Southeast in her spare time.

Notes

Transcript

[00:00:00] Hello and welcome to the Gran Touring Motor Sports Podcast Break Fix, where we’re always fixing the break into something motor sports related. The following episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce and the Arts Inger.

Charlotte’s Glory, the NASCAR Hall of Fame in the Queen City by Hannah Thompson. Hannah Thompson is a cultural historian of the Carolina Piedmont and is new in the museum field. With her current position with the Gaston County Museum of Art and History, Ms. Thompson also helps restore Coca-Cola ghost signs throughout the southeast.

In her spare time, she examines the history of the NASCAR Hall of Fame from its inception in 2001 through the Growable. Bringing into the consideration, while Charlotte was selected as the seat for the Hall of Fame and how the hall has affected NASCAR and its fans, Ms. Thompson suggests that Charlotte is often overlooked in motor sports history despite its [00:01:00] lasting impact on the auto racing world.

Charlotte’s Glory, the NASCAR Hall of Fame in the Queen City. And here is Hannah Thompson joining us from South Carolina. Well, first I’d like to start by saying thank you to everyone in Watkins Glen, who made it possible for this symposium and this opportunity to present to you from Zoom. So it was race day in 1960.

The newly built Charlotte Motor Speedway was beginning to spring to life. Andrew Andy Thompson made his way to the pits with his paint cart in tow. He was there to paint the driver’s names and sponsorships onto their stock cars as a signed painter for Coca-Cola. Consolidated in Charlotte, North Carolina by trade.

Thompson entered the automobile racing circuit as both an artist and a race fan. As his reputation grew at the track, so did the number of cars he lettered on race. Bobby Isaac, fucking buddy Baker, fireball Roberts and Wendell Scott. Were all names intimately familiar to Thompson [00:02:00] as his personal photos and accounts.

Document Thompson’s artistry was only one of many ties NASCAR had to the city of Charlotte, also known as the Queen City. And his legacy of painting race cars continues to live on through those cars on display in the Glory Road Exhibit at the Necar Hall of San, located in the Queen. Andy Thompson, my grandfather was one of the thousands of people in the Charlotte area who helped establish the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing nascar, and whose lives anchored the sport in the city that would become home to its Hall of Fame a half century later.

Despite its role in the development of Charlotte and in the lives of individuals like tbs, NASCAR has attracted surprisingly limited attention from academic. Most of the literature written about the sport focuses on its origins for bootlegging illegal production, distribution, and sale of alcohol during the prohibition era or early organized racing efforts.

In contrast, there is little scholarship that examines the relationship between Charlotte and [00:03:00] NASCAR specifically with primarily local historians such as Tom Chet or Heather A. Smith, even briefly investigating the relationship. This lack of scholarship and attention to NASCAR within Charlotte is due, at least in part, to the simple fact that historians, other than sports historians such as Dan Pearson, Markel, often marginalized sports history as a pop culture pastime rather than a rigorous academic discipl.

I in turn seek to play Charlotte as a key player in motorsports and especially NASCAR history throughout the last half century. An endeavor to answer why it took so long for a NASCAR hall of fame to be built. Charlotte’s geography was a significant factor in the Queens city becoming a major racing hub, both through its positioning in the United States and through the abundant red Clay in the Piedmont.

This geography factor in combination with Charlotte’s growing economic and cultural standing throughout the second half of the 20th century led to nascar adopting Charlotte as an unofficial racing hub by 1965, as well as NASCAR [00:04:00] executives eventually choosing Charlotte to house the NASCAR Hall of Fame in the early two thousands.

Solidifying the role of Charlotte in racing in nascar. The NASCAR Hall of Fame’s position alone testifies to Charlotte’s impact on the racing industry and the racing industry’s effect on Charlotte as the queen city itself headed by Mayor Pat McCrory at the time was the group lobbying of hardest for the whole seat in Charlotte.

The hall in Charlotte is the only hall of fame completely devoted to and licensed by nascar, other halls of fame to vote themselves to motor sports in general, though they may discuss Nas. Additionally, the NASCAR Hall of Fame is the only hall of Fame located in Charlotte. Further speaking to the importance of the Motorsport industry to the queen, So Charlotte and the state of North Carolina have been dubbed NASCAR Valley by many motor sports fans, journalists, and historians alike with over 90% of NASCAR teams as well as pivotal manufacturers such as Holman Moody, located within the greater Charlotte metropolitan area.

It’s safe to say that Charlotte is the [00:05:00] beating card of NASCAR now as a crash course for those who are unfamiliar with why Charlotte in particular houses the majority of race teens. It mostly comes back to ge. When tracks were still dirt and races were just beginning to be sanctioned by one governing body, it was necessary to have red clay.

This particular clay was perfect for motorsports as it compacts down into a hard like surface that didn’t allow vehicles to sink, like the sandy white clay to the east, or the black spongy clay to the west. It also allowed for drivers to take turns at faster. . Red Clegg can only be found in a small portion of the country, specifically in the Piedmont that runs through some of the eastern states, primarily Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia.

Once NASCAR was found in 1947, it was only natural for teens and parts manufacturers to congregate in one city. Daytona Beach were NASCAR’s. Executive offices are located, was too small and not central enough for teams to travel around the country easily for. auto racing was already a distinctly [00:06:00] southern sport due to the abundant red clay, and it was therefore not likely for NASCAR Valley to settle outside of the Piedmont.

Charlotte is directly in the center of the Eastern seaboard, equal distant between New York City and Miami, and houses 53% of the nation’s population within 650 miles. By the 1980s, Charlotte Douglass International Airport had grown into a large bustling hub, coupled with the numerous major interstates and highways through and around the queen.

City teens had no issues traveling to races, and it was easy to have parts shipped if the manufacturer wasn’t already located in metropolitan area. There’s one for a tiny detail that caused Charlotte to unofficially become the heart of Nas. Atlanta, which was the original unofficial center of nascar, made NASCAR leadership drivers and fans angry.

When Atlanta leadership decided to censor who could race at the city own raceway in the late 1940s in retaliation, NASCAR packed up and made its way to Charlotte, which had fewer qualms about having a [00:07:00] stereotypically lower working class population. Already a larger mill centered city. Charlotte did not become a banking center, the second largest in the country, a majority middle and upper class until the 1980s after NASCAR Valley had already been well established.

NASCAR is one of the largest industries in North Carolina. Despite not being a highly accredited sport by the general public in Charlotte, the greater Charlotte region and Carolinas in general have hosted some of the largest races on the NASCAR strictly stock series calendar, and have produced some of the largest sponsors and players in the sport.

Sponsors like Firestone Tire Rubber Company and stp, a motor oil company, found a niche area to test and promote their. NASCAR was able to create hundreds of jobs through the creation of more and more teams, while being able to put hundreds of thousands of dollars of revenue into local economies each race weekend.

Many former NASCAR pros like Rick Hendrick also eventually make their way to owning car dealerships in the Charlotte area, furthering the economic impact to the [00:08:00] area. However, there are three main areas that NASCAR has an economic impact on. Charlotte Motors, Speedway, Motorsport related industries in the Charlotte region, and of course, the NASCAR Hall of Fame.

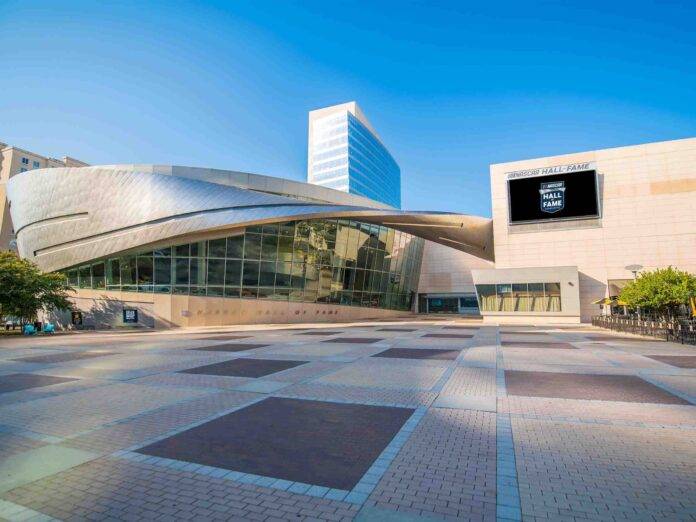

On May 11th, 2010, the NASCAR Hall of Fame opened its doors to the public for the first time seated almost at the very heart of Charlotte, North Carolina. The Hall of Fame remains committed to presenting the history of both competitive stock, car and stock truck audit racing, designed by Imk architect of the Glass Pyramid in front of the Lous.

In the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, the hall is a beautiful, modern building that contrasts with the rest of the queen city skyline of 1980s era high-rise buildings. In case you haven’t had the opportunity to visit the hall yet, there are two central exhibits, glory Road and the Hall of Honor with the rest of the hall, focusing on the steam aspects of NASCAR with interactives built in throughout, to test your knowledge based on the surrounding exhibits and even an opportunity to place your driving skills against other visitor.

So [00:09:00] why is this matter? Why study the NASCAR Hall of Fame in particular when there are a multitude of motor sports halls of fame? Hall is unique and that is the only one devoted solely to the commemoration and promotion of NASCAR and not motor sports in general. It is also an interesting case. It is not often that we can study a still young institution like Hall.

The last decade has seen a large number of changes for NASCAR and the Hall of Fame, particularly to the induction process and the added emphasis on STEAM education. Making it an ideal time to examine the hall and its progress since inception in 2000. When the NASCAR Hall of Fame was first proposed in the early two thousands, there was quite a bit of speculation surrounding where it would be placed.

The final three contenders were Charlotte, Atlanta, and Daytona Beach. The Kansas City and Richmond were also considered in the early days compared to Atlanta and Daytona. Charlotte may not seem like the most logical place but the Hall of Fame. However, as I said earlier, Charlotte had already been dubbed NASCAR Valley decades prior to this announcement due [00:10:00] to the high volume of motor sports activity within the.

The proximity of a large international airport and major interstate roadways assisted in placing NASCAR within the Queen City back in the 1960s and earlier days of nascar. A 2006 New York Times article noted that Brian France, the chairman of NASCAR at the time, had saved both Atlanta and Charlotte were ideal for the hall, but never mentioned Daytona Beach, most likely due to its limited fan traffic and being off the beaten path despite being the cradle of the NASCAR organiz.

And within driving distance the other Florida attraction, therefore leaving Atlanta and Charlotte as the last two possible locations for the hall. However, noted Motorsports and NASCAR historian Dan Pierce claims that Atlanta lost the bid for the hall in 1945. Before a Hall of Fame was even imagined, the event Pierce references is when Atlanta city officials and religious leaders cracked down on who would be allowed to drive in races at Lakewood Park.

The city owned raceway following World War II when bootleggers were still [00:11:00] prominent. Drivers, promoters, and mechanics. Additionally, the Atlanta Middle class, were trying to distance themselves from anything reminiscent of the southern reputation of being poverty stricken, a majority working class population.

Such stereotypes of NASCAR continued to play the sport, but this particular instance solidified the fact that Atlanta had, on some level, irreparably harmed its relationship with the NASCAR organization in the mid 1900. The attempted erasure of Atlanta’s bootlegging history by city officials in the 1940s by means of banning former bootleggers from racing led to Atlanta’s exclusion as the premier racing hub in the Southeast, as well as the seat for the hall of fame.

Comparatively, the historic aspect of the positive relationship between Charlotte and nascar, the public funding guaranteed by city of. That NASCAR leadership was looking for, and the fact that over 90% of racing teams are also housed in and around the city, all ultimately resulted in NASCAR officials choosing Charlotte to the location of the Hall of Fame.

As the officials [00:12:00] felt that these reasons spoke to the true history of nascar, which is a large factor of the Hall of Fame’s purpose, one of the largest factors in choosing a final location for the hall was which city had the sustainability for the hall 15, 20, 35 years down the. All three final contenders had the potential for that sustain.

Making them all viable options. However, Atlanta and Charlotte have a slightly higher ability to support the hall long term as they constantly see new construction and new attractions that draw visitors from all over. The majority of fans interviewed at the 2006 Daytona 500 even said they would prefer Charlotte of the three contenders to have the hall, mainly due to the number of race chefs in the area.

Luckily, for those particular fans and for Charlotte, the Queen City was chosen by NASCAR leadership later in 2000. The city of Charlotte owns the Hall and the Charlotte Regional Visitors Authority, not NASCAR runs it. While NASCAR does not receive any of the Hall’s direct revenue, there were major benefits to the Queen City owning and [00:13:00] operating hall.

The Hall of Fame overall cost 189 million, which included the Hall Ballroom and the convention center office space and a parking deck. Charlotte guaranteed public funding to take care of the entire cost by raising the hotel occupancy tax by 2%. Private bank loans and through the selling of state helped land parcels.

Though NASCAR did end up purchasing the office space from the city and now run almost all of their media operations out of the Charlotte. NASCAR does, however, still receive the byproducts of increased fan activity within the city around races as there are at least two races in Charlotte every year, as well as getting younger demographics involved with auto race culture through school and extracurricular group field trips.

NASCAR also intended for the Hall of Fame to assist in increasing NASCAR’s fan base to what it was before Dale Earnhardt. Though it is still difficult to gauge pure van base versus visitors to the hall, which includes school field trips, non-fan base groups, people using I 77 en route to Florida, [00:14:00] travelers coming through Charlotte Douglas International Airport, and visitors to the convention center in the same complex as the hall.

The Hall’s mission statement notes that the hall aims to drive economic impact for the Charlotte region. Honor the heritage in history of NASCAR and cultivate loyalty for both the NASCAR Hall of Fame and NASCAR through delivering a multifaceted experience that is interactive, entertaining, educational, immersive, and engaging.

While the statement is worded generally enough to address all audiences, it also aims specifically to create new fans through its third point to cultivate loyalty. NASCAR fan numbers have decreased for a number of reasons, including other more diverse ways of spending leisure time, growing costs of fuel, lodging, and accommodations in an aging fan base.

Additionally, the tragedy of Earnhardt’s death in 2001 as well as other superstar drivers, retirements caused the fan base to decline after its peak in 2005. The Hall of Fame attempts to supplement the fan base by appealing to those demographics [00:15:00] typically not found within the sports fan. The C R V A who run the hall were gracious enough to give me access to the fiscal report since 2017.

There was some data from 2015 included in the 2017 report. Despite C R V A claims that visitor numbers have grown over the years, the report show that visitor numbers have continually been decreasing at a marginal rate. For reference, the NASCAR Hall of Fame had over 275,000 visitors during its first full year in operation, but the number of visitors coming in second only to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown new.

In 2019, the last full financial year on record for the hall, there were around 70,000 visitors. If my calculations are correct that the C R V A is not specific about visitor numbers past the first year or two of the hall’s operation as a point of reference, other sports hall of fames see anywhere from over double to quadruple that number of visitors in a.

However, the first 12 months after the NASCAR Hall of Fame [00:16:00] reopened in September, 2020, saw over 90,000 visitors a roughly 35% increase over 20 nineteens visitor numbers, and there is still room for that number to grow. There are almost 150,000 students in the Charlotte Mecklenburg School district alone, which is where Charlotte and the Hall of Fame are located.

For fiscal year 2021, the Hall of Fame saw just under 11,000 students, not exclusively from the Charlotte Mecklenburg District, but this number continuously declining for the last several years. The pandemic and subsequent innovations museums had to create because of the pandemic, provide potential for the hall’s educational outreach to grow exponentially.

Educational outreach and bringing in families as new visitors because of these students is vital to the ongoing sustainability of the museum. Which was discussed in 2006 when choosing a final location for call. The overall decrease in visitorship and educational programs could be from a multitude of factors such as lack of inclusivity and diversity in honorees.

The [00:17:00] slow change in certain exhibits such as Glory Road, which only changes every three years or other cheaper educational opportunities in the. The number of visitors to the NASCAR Hall of Fame has dropped off since the inaugural year. Despite the Hall’s staff increased awareness of Charlotte’s largely middle class population with exhibits designed with diverse demographic engagement in mind.

Because the middle class population is not the primary demographic drawn to NASCAR as a sport, and by extension it’s other attractions like the hall spaces like the Hall are an instrumental way of throwing both knowledge and the fan base of the sport. More traditional NASCAR forms like Charlotte Motor Speedway are still a large factor of the economic and cultural impacts in motorsports are in Charlotte.

The Hall of Fame reaches demographics that would not feel quite at home at the Speedway due to stereotypes surrounding the sport as a white, southern and lower class sport. Continuing the original narrative of NASCAR as a working class sport. As of 2004, when this graphic in front of you was printed, [00:18:00] there were more than 400, almost 700 by 2012 MetaPort related businesses in the Charlotte region.

90% of NASCAR teens in the Charlotte region and 2,750 MetaPort industry jobs in the Charlotte region. And then there were over 20,000 by 2012 exemplifying exponential growths of the motor sports industry in the Queen. The majority of these are located in Mooresville and Concord areas where teams are located.

Likewise, the motor sports industry and the state of North Carolina in 2003 had 12,292 jobs directly related to the motor sports industry. Created 24,406 new jobs in North Carolina and generated over 5 billion in revenue. A steady figure for at least the last 20. With salaries for those in the motor sports industry in the top 3.6% of highest earnings.

As the exponential growth of job opportunities in the industry continues to rise, so does the concentration of [00:19:00] motorsports businesses within the Charlotte area. Despite this clipping before you being almost 20 years old, there is still a high concentration of better sports related businesses, including NASCAR specific businesses and teams in the same general areas.

Some of the teams have moved since 2004, though others have moved into the Charlotte area since. Over the last five years, the economic impact of the hall was at a high with 72 million for the Charlotte area and 39.1 million in direct spending. As of 2019, the museum had a roughly 58.3 million economic impact on the city visitors traveling an average of 564 miles to get to the city.

In addition, visitors averaged a three day overnight trip with approximately 37% of visitors coming to Charlotte with the primary intention of visiting the. These visitors also averaged an expenditure of $830 per party in the city. Both the direct and indirect economic impact of the Hall and motorsports have decreased in recent years.

While there is not a singular [00:20:00] reason for this pandemic hit every industry, including sports and especially manufacturing card. The next few years we’ll hopefully see a rise in the economic impact in the Charlotte area, as well as increased visitors and educational outreach, and we can get the numbers back up to what they were at the height in 20.

The impact of the motor sports industry is still astounding and makes one question why native sher audience do not log NASCAR as much as other sports like the Panthers football team or the Hornets basketball team, while city leadership and media do. Part of the answer is the negative connotations in stereotypes surrounding auto racing in its origins while another is that there are simply other and potentially more engaging ways to utilize leisure time than there were when nascar.

The Hall of Fame seeks to remedy these issues by engaging demographics other than those typically associated with nascar. By reworking the traditional auto racing and NASCAR narratives, they’re focusing on steam aspects of the sport rather than making the hall all about NASCAR’s history. The continuing issue, [00:21:00] however, is convincing enough non-fans to visit the hall and promote NASCAR as just as fun and engaging as other sports like Fall or.

Back to our question of why did it take NASCAR so long to create a Hall of Fame for itself? Unfortunately, there’s not one perfect answer that I have been able to find. NASCAR has been represented heavily in other halls of fame, such as the International Motor Sports Hall of Fame in Talladega, and a vast majority of teen shops have their own many museums attached that fans are welcome to visit throughout the year.

Also possible that fans were so accustomed to having a dominant oral tradition in honoring their racing heroes and saw no real need for a specific place to lad them. The Hall of Fame, however, has provided a welcoming space for fans and non-fans alike to learn about the steam aspects of NASCAR and motor sports.

In a more general sense, it’s also provided a space for teams to hold press conferences, unveilings in other swee with the whole hosting over 300 events every. Has the hall lived up to its 10 year [00:22:00] expectations? Yes and no. It’s difficult to gauge success though when two years of its very short history have been odd because of the global pandemic the next 10 years and how the hall continues to evolve will really show the long-term sustainability of a NASCAR hall of fame and weather.

Charlotte was indeed the best choice in location. How the hall chooses to evolve following the Covid 19 pandemic and major social movements such as the Black Lives Matter and Me Too Movements that focus on inclusivity and diversity will also determine the hall’s future success as a major sports Hall of fame.

And that is it. Thank you very much. Thank you, Hannah. Thank you. I’m Tom Shme. I was executive director of the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame and Museum in Knoxville, Iowa for 19 years, and then curator for another nine. Our perception at the time that Charlotte was successful in getting the bid. Was that it was a low, absolute, low ball application, that there was no way that it was financially sustainable.

Just sitting here today, I brought up an [00:23:00] article in the Charlotte Observer, October 16th, 2019 by Jen Roth Hacker. The title is Everybody is Losing Money on the NASCAR Hall of Fame. It talks specifically about the dollars and the deals with NASCAR to wa, you know, some of the revenue. It says right in the article in the Charlotte Observer that the Hall of Fame lost a million dollars each year for the first five years.

You said that it’s hard to get those financials now pre pandemic. Do you know what it was losing in a year or what it was making in a year? I do not know the specific numbers. C R V A has been very list slipped on all of their financial records. I do know that they promote the Hall of Fame as being one of their most successful take.

That how you will endeavors that they run. They run some of the major entertainment centers within the city. I do know that the earlier years they were losing money at the Hall of Fame. It’s continued to be a struggle. . I think part of that is that it’s because the city itself is running the Hall of Fame and is not a NASCAR run [00:24:00] entity.

Thank you. Okay, Hannah, I think you covered it all. Excellent. Thank you very much. All right. You take care. All right. Thank you again. Mm-hmm. Bye-Bye. This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series.

The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world. The Center welcome series researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race, drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events.

To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The s a h actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the [00:25:00] understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the s A h, visit www.auto history.org.

If you like what you’ve heard and want to learn more about gtm, be sure to check us out on www.gt motorsports.org. You can also find us on Instagram at Grand Tour Motorsports. Also, if you want to get involved or have suggestions for future shows, you can call our Texas at (202) 630-1770 or send us an email at crew chief gt motorsports.org.

We’d love to hear. Hey everybody, crew Chief Eric here. We really hope you enjoyed this episode of Break Fix, and we wanted to remind you that GTM remains a no annual fees organization, and our goal is to continue to bring you quality episodes like this one at no charge. As a loyal listener, please consider subscribing to our Patreon for [00:26:00] bonus and behind the scenes content, extra goodies and GTM swag.

For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can keep our developers, writers, editors, casters, and other volunteers fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, gummy bears, and monster. Consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without fans, supporters, and members like you, none of this would be possib.

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App: |  |  |

Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)