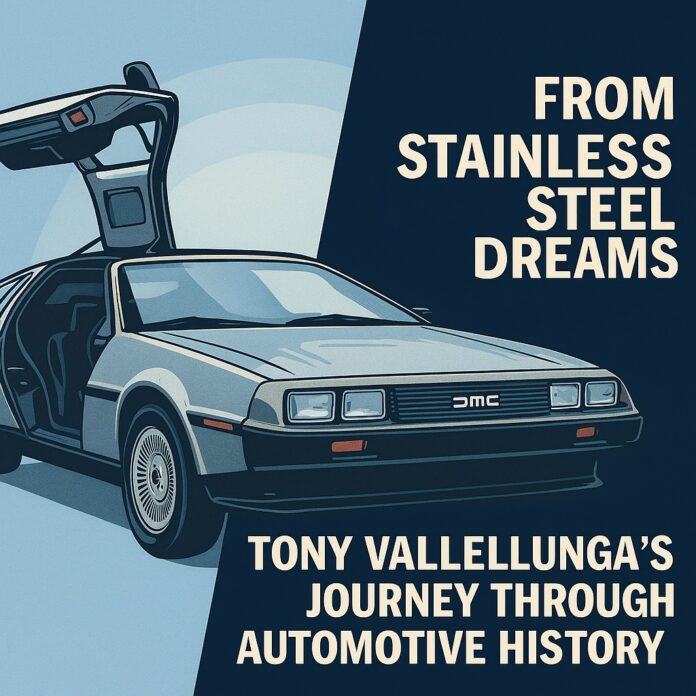

When you think of iconic cars, names like Ferrari, Porsche, and DeLorean come to mind. But behind every legendary vehicle is a legion of unsung heroes – designers, engineers, tool and die makers – who transform imagination into reality. On this episode of the Break/Fix podcast, we meet one of those heroes: Tony Vallelunga, Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality at DNG Motors, whose career spans over four decades in the heart of Motown.

Tony’s origin story begins with a 1957 Chevrolet and a father who encouraged curiosity. From tearing down lawnmower engines to wondering how fenders were formed, Tony’s fascination with mechanical magic led him to pursue manufacturing over mechanics. Detroit’s rich ecosystem of tool and die shops became his playground, and MSI Prototype and Engineering – where he met John DeLorean – became his proving ground.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

In the late ’70s, Tony found himself operating a 1200-ton hydraulic press, crafting stainless steel gullwing doors for the original DeLorean. “If you can master stainless, you can master anything,” he says. The process was complex: from blueprint to plaster model, to Kurzite alloy dies, to final press. Each panel required multiple dies, and stainless steel’s low ductility made it a formidable challenge.

- Spotlight

- Notes

- Transcript

- Highlights

- Bonus Content

- Learn More

Spotlight

Tony Vallelunga - Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality for DNG Motors

With well over 40 years experience in the heart of American auto-making in Detroit, our guest has seen it all.

Contact: Tony Vallelunga at Visit Online!![]()

Notes

This Break/Fix episode hosts an interview with Tony Vallelunga, Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality at D&G Motors, covering his extensive experience in the automotive industry. The discussion delves into Tony’s early fascination with cars, his technical journey in Detroit’s automotive sector, and his pivotal role in manufacturing the original DeLorean DMC-12. The episode also explores the complexities of tool and die processes, the challenges of working with stainless steel, and modern advances in automotive manufacturing. Tony reflects on the changing landscape of the industry and shares insights into the ongoing development of a new DeLorean model, emphasizing collaboration, innovation, and educating the next generation through STEM programs.

- How did you start your career? What ties do you have with the DMC-12? Where did you go from there?

- How has the manufacturing line changed since you started your career in the automotive industry?

- As technology starts to replace some of the manufacturing positions, does that open up the door for other opportunities within the automotive industry?

- How did you find yourself to be the Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality for DeLorean Next Generation?

- What gets you excited about being involved with this project?

- How do you see this program impacting both its participants and the industry?

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] BreakFix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autosphere, from wrench turners and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of petrolheads that wonder. How did they get that job or become that person?

The road to success is paved by all of us because everyone has a story.

Crew Chief Eric: When people look at a car, they tend to immediately associate it with a brand or maybe just a family name like Ferrari, Porsche. Or DeLorean, but in actuality, it takes hundreds of people to make a car truly come to life from the imaginations of designers to the complex calculations of engineers and programmers down through the manufacturing process with tool and die teams, chassis builders, as well as.

assembly and quality assurance. With well over 40 years of experience in the heart of American automaking in Detroit, our guest has seen it [00:01:00] all. And in the late 70s and early 80s, he could be seen running what was at the time a state of the art 1200 ton hydraulic press, the largest of its kind in any plant.

It was his job to take new development dies and make them into parts for a very special build. He fondly remembers getting the orders one day for gull wing doors in stainless steel, suddenly realizing that these parts were destined for the new DMC 12. With us tonight to talk in depth about the manufacturing side of the automotive business is Tony Vallelunga, Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality at D& G Motors.

And I’d also like to welcome back my co host, the one and only Kat DeLorean to BreakFix. So welcome to you both to the show.

Kat DeLorean: Thank you for having us.

Crew Chief Eric: Yeah, thank you for having us. So Tony, like all good break fix stories, everybody has a superhero origin. So talk to us about the who, what, when, and where of Tony V, the petrol head.

How did it all get started for you? Did you [00:02:00] come up from an auto making family or did you get interested in cars as a kid and take us on the journey into how you started working in Motown? Well, the

Tony Vallelunga: journey started when I was a kid. My father I had a 1957 Chevrolet. It was fairly new at the time, but he taught me how to do maintenance on it.

But when I saw all the fancy styling on it, all the chrome, the bumpers on the hood and everything else, I was just in awe. I had a curiosity how mechanical things ran. You know, when I was a kid, I asked my father if I could tear apart a lawnmower engine. He said, sure, go ahead. From there, my curiosity was how do we make a fender, how do we get a quarter panel, how do we make cars, what’s involved?

And it just bloomed from there.

Crew Chief Eric: So I’ve heard tell stories of you grow up in the greater Detroit area, there’s certain schools that everybody [00:03:00] goes to. I even met somebody the other day that said, you know, I went to school at the same place that John DeLorean went. Not the same year, but the same place.

They’re all sort of involved in the automotive world at some point and in some way, especially being in Detroit. How did you find yourself coming up through the system? And then where did you end up? Like we know John’s story, right? He started at Packard and then he moved to other places and so on down the line.

So

Tony Vallelunga: My journey started in school, actually junior high. They taught us how to do household wiring, wood shop, metal shop, and so on, carried through high school. I was in on all those classes. I also had three years of auto mechanics. You had auto one, auto two, and then you had the technical course in your third year of high school.

Gear you to whatever you wanted to do after high school. So I thought about, do I want to work on cars? Or do I want to build cars, right? I had an opportunity. Well, I chose to build instead of being a mechanic. [00:04:00] Then I had the fascination of manufacturing. I was just always so curious. Well, being in a Motown here, back years ago, there was a, almost a tool and die shop in every corner.

Crew Chief Eric: I remember the story of Tucker, right? He was doing tulip dye out of his shed.

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, that’s just how it starts, right? There’s all kinds of manufacturing around here, everything you can imagine. I just always wanted to stick with stampings. I had a curiosity how you take a flat piece of metal and turn it into a fender.

It’s truly magical.

Crew Chief Eric: So is that something you went to school for? Is that you learned it on the floor of the factories?

Tony Vallelunga: I learned it on the floor of the factory. There was some schooling, some taught on the floor. It was your choice however you wanted to pursue it. But most everything I learned was on the floor.

Even some of your small shops will have classes and still get credits through whatever classes they give you. You get college credits for it. You could either go part time to college, work full [00:05:00] time, or however you want to do it. But most everything I learned was on the floor. You know, you learn by doing.

Kat DeLorean: Weren’t you in an apprenticeship program, much like we want to help kids go into when you first started?

Tony Vallelunga: Absolutely. You know, the apprenticeship program, you have to have four years of college or eight years experience. So it still will get you the job you need, but it’s just how you want to pursue it.

Crew Chief Eric: So where did you cut your teeth?

Tony Vallelunga: At MSI Prototype and Engineering, right where I met John. That was the start of it. I had worked previously in smaller so called job shops. Went over there and it was a perfect opportunity. We did everything there from woodwork to plaster to foundry. Everything you could imagine for manufacturing.

Everything you ever needed. Just a golden opportunity I had at the time.

Crew Chief Eric: So this would have been circa the late 60s, early 70s then?

Tony Vallelunga: Mid 70s.

Crew Chief Eric: So John had started to have some gray coming in right at that [00:06:00] point. So what was your first impression of him?

Tony Vallelunga: A walking saint. Uh, the only way I could describe it, right?

He was the man of the day.

Crew Chief Eric: Would you say his reputation preceded him, especially all the work that he had done at Pontiac, at Studebaker and Packard, etc?

Tony Vallelunga: And so on, yes. He did very well for himself. We did prototype work, but we knew when John came through, we knew who he was, we knew that it wasn’t just any car, it was a Galwing car.

Not only was it a Galwing car, but it was made out of stainless steel. Totally, totally awesome. Awesome experience to be able to do that because it was unheard of. Did stainless steel before, but never to this extent. They would put stainless steel trim on cars or gas tanks were made out of stainless steel back in the day.

To have a gallwing car stainless steel was the most awesome thing in the world. I knew when we were doing this, it was the most awesome thing in the world. And if you can master stainless, you can master [00:07:00] anything else. What an experience, you never forget it.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s walk that back and unpack it a little bit.

It’s a bit of a marvel to see how you can take a flat sheet of steel or even stainless steel or aluminum or something else and suddenly it turns into a fender. So for our audience that’s kind of scratching their heads going, well, how does that exactly work? Can you kind of talk us through it? Maybe boil it down and make it easy for folks to understand.

Tony Vallelunga: Start with the designer, right? They give us the blueprint. Back then we turned them into wood models, copied them and plastered. We would do a dye development. So, in order to take apart, we just can’t take the exact shape and say, hey, we’re going to stamp it out. We have to develop curves and shapes for stretch and form to eliminate wrinkles, right?

So, we call that draw dye development. So, the guys who do this can basically, back then, look at a part. See where we need to stretch it, where we know where the wrinkles are going to come in. So they develop the dye along with the part. Once they do that, they copy it [00:08:00] out of plaster, then they pour the dye.

We’ll say, for prototype, we’ll use Kurzite. And Kurzite’s a soft alloy that can be formed and shaped quickly. And once they pour the dye, we have a tracer machine that would cut off the plaster to cut the right patterns in the dye. They pour it, clean it up a little bit, we throw it in the press and it burns.

It’s simple in a way and in a way it isn’t. Once you do the dye development and it’s operational, when you get it running, it’ll run forever.

Crew Chief Eric: But you have to create… tool and die for every panel and component that you’re pressing out, right? So there’s a left fender and a right fender and the doors and the quarter panels and the trunk and the hoods and all that kind of stuff.

It’s a pretty big operation to basically punch out all the sheet metal of a car, right?

Tony Vallelunga: Huge. Very huge. Yes.

Crew Chief Eric: So are chassis also stamped out or sections of them?

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, absolutely. Yes, everything is.

Crew Chief Eric: To describe how big a facility would be to build [00:09:00] a single car, not talking like all of Chevy’s different models that they have, because you have to have tool and die for every single thing, which boggles my mind when you see car designers changing little things every year.

It’s like you have to re up all of your tool and die every time you make a change. How big are these facilities just to create one car, something like the DeLorean DMC 12?

Tony Vallelunga: Massive. Yes, just massive. The dies alone. So, uh, for each die, for each part, there’s a checking fixture. So if you could imagine all these parts that are in a car, all have fixtures to check them on.

It’s just way huge. Way, way huge.

Crew Chief Eric: How many different tools and die are there on average to a vehicle? Regardless of its size versus, you know, we won’t get into convertible versus minivan.

Tony Vallelunga: For each part on a car, it takes three to six dies to make. Usually your outer skins will take three to four, but any other complex parts takes at least six dyes.

Crew Chief Eric: So that’s a layered approach then, you use the first dye to make an initial [00:10:00] shape, the second one to then stretch that shape and continue from there.

Tony Vallelunga: So you have a draw dye, right? It’s the initial form dye. Once that’s developed, the rest of the dyes are pretty fundamental, right? You have a restrike trim.

Maybe a little reform, but the most important part is to get the first draw die developed.

Crew Chief Eric: In the instance of talking about the original DeLorean, why is stainless so much harder to work with than a lot of the materials we use today?

Tony Vallelunga: It’s tough material. We look for ductility and it’s the ability to stretch without breaking.

Stainless steel is tough. It has less ductility, so it takes more work on the die to get it to form certain shapes. It just takes longer. Regular steel has more formability to it than stainless. For most people that do tool and die work, stainless steel is rare. Most people will have a learning curve on it.

Into you get it

Crew Chief Eric: the folks at [00:11:00] Kohler and Delta know how to do when they’re making sinks, right? But they’re all square so it’s not too bad

Tony Vallelunga: Well, right, but you have in a car you have all kinds of exotic shapes, right?

Crew Chief Brad: Exactly

Tony Vallelunga: and remember for most manufacturers even well today we build cars at one a minute.

So these things have to run And if you can imagine all the dyes, right? Well, we can’t run them all the time. We have to dye set them all the time, right? And then various presses. So it’s a huge process. It really is.

Crew Chief Eric: Is there heat involved in the pressing process?

Tony Vallelunga: On rare occasions, yes. Mostly it depends on whether they try not to, right?

But for exotic shapes, yes, sometimes there is heat involved.

Crew Chief Eric: A little bit of persuasion, right?

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, yes. Yeah, that’s very important, right?

Crew Chief Eric: You were talking about the ductability of the metal. There’s also the malleability of the metal, right? Its ability to fold without breaking as well. How different are the dyes for metals versus those [00:12:00] of, let’s say, carbon fiber or fiberglass?

Or are they the same?

Tony Vallelunga: So for carbon fiber, right, you use a type of vacuum form to get your shape, but it still has to be cut and trimmed and holes put in and everything else. But to get your shape, yeah, it’s done the same way. You gotta cast it, get your shape.

Crew Chief Eric: Could you use an old die, let’s say, the left front fender of a DeLorean, and suddenly make it out of fiberglass or carbon fiber instead of stainless?

Or do you have to make a whole new die?

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, it’s a different type of die, yes. It’s a different process. But you

Crew Chief Eric: could use the old die as a mold.

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, once you have the shape, yes. Yes, you can do that.

Crew Chief Eric: We’ve been nerding out here, Kat. Sorry.

Kat DeLorean: As he’s describing all of these processes, I have a picture on my desktop of the old car and the new car.

So if you see me getting lost, it’s because I’m listening to him describe. Doing all of these processes and thinking about how it would apply to manufacturing the new car. Which is kind of [00:13:00] what’s happened to my brain lately. Everything goes back to manufacturing the new car. Tony’s been talking to me for quite some time now about all of the different processes that go into building a car.

It’s always amazing to hear just how much goes into a car in a car a minute. I hadn’t heard that. That’s staggering. Astonishing. Can’t even eat M& M’s

Crew Chief Eric: that fast. I mean,

Kat DeLorean: they’re

Crew Chief Eric: flying through these cars. So on our show, we talk a lot about Design and cars and how styles have changed over the years. And there’s been periods for just certain shapes.

There was the wedge period in the seventies and he had all the boxy cars with round headlights in the eighties. And going back to what you were talking about in the fifties, it was all the big fins and the swooping designs versus. The cars that came before them were very much, let’s say beetle like to use a car analogy.

Are there certain shapes that are easier or harder to manufacture than others?

Tony Vallelunga: Absolutely. [00:14:00] Yes. Yes. Yes.

Crew Chief Eric: So I’m going to guess the square cars are probably easier to make than the round ones.

Tony Vallelunga: Ah, really? Every shape has its own challenge. Never say never, right? Yeah. They the day.

Crew Chief Eric: I can’t believe the guys that were hand hammering out the old car from the 30s and 40s and stuff. I mean, that’s just masterful work in and of itself. I wonder when you look at the DMC 12 versus the DMG and you look at their shapes, obviously they’re radically different. One inspired the other. It’s an evolution of a thought as we talked to Angel Guerrero on a previous episode.

So when you look at it from a more technical approach, you compare the two cars having worked on the original and now gearing up. to tool up and die the new car. What are some of the things that you see on the new design that may pose a challenge in the manufacturing process or something you go, Oh my God, this is so much easier than the early cars were.

Tony Vallelunga: So I I’ll look at something and picture it in my head and I can [00:15:00] envision how to make the dyes were to split them off that right. What will work and not work. I look at the car. And I already have in my head what I would want to do with it. I look at the shapes, and I look what’s easy, what’s going to be hard on it.

Maybe if we made the hood, I would look at it and say, hey, well, maybe we’ll have the hood shape and fenders a certain way. And this is where we’ll body open the hood in a certain area. Because I know in my head that we can make a die to do this. And still have it look right and still be functional. The shapes, how many dyes, right?

It just comes automatic to me. So that’s what goes through my head when I look at a vehicle.

Kat DeLorean: I want the superpower, Tony. I want to be able to like look at a car and just be able to pick it apart and see it. I can imagine in your head like explodes into body panels and you can turn it around.

Tony Vallelunga: It does.

Yeah, I’ll look at it. I’ll look at a shape. Okay, well, that’s doable. And maybe this won’t be doable. So we’re going to change this. And [00:16:00] that’s just how I think that’s my thought process. But yeah, I could just look at it. No, but today that’s all different today. We have Draw dye simulators that will simulate the forming of metal in a dye, right?

A certain way we’re going to tip the dye or shape it.

Kat DeLorean: How has that improved the manufacturing process? So being able to actually use the technology before you have to put it into production. How has that improved the whole overall process? It

Tony Vallelunga: helps most people out who don’t understand draw dyes. Because when they see it in a simulation, it clicks in their head.

Oh yeah, right? So it makes sense. But we didn’t have draw a die simulators years ago. We just knew in our head from doing. Usually a generic fender or a generic quarter panel or a generic door. The guys on the floor know how to make that draw a die, how to develop it. It was all up in our heads, right? They knew where we needed to [00:17:00] stretch, and not stretch, and hold a certain way.

But today, we have Draw A Dice simulators. They’re about 80 percent correct.

Crew Chief Eric: So, you’re already pretty intimate with how to stamp out the Gullwing doors, right? The doors, the doors, the doors. But when I look at the new design, I look at that front end, and as gorgeous as it is, it Kind of throws me for this one piece clamshell similar to like a Viper or a Lotus Elise and with the reverse popping hood like an E30 or a Corvette.

So do you see that as maybe one of the more challenging pieces to create on the new car?

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, absolutely. When you look at a car and you look at all the shapes, right, you have to remember a die and a press only run straight up and down. So when you design your die, you have to design to shape in the tip of the actual, say, we’ll say a fender, right?

What has to be tipped a certain way for backdraft angles, because that press only runs perpendicularly, [00:18:00] right? That’s it. We know this, so we figure out how we’re going to get the shape. Do we need another die to get a certain angle to kick it in? We have to remember that. Press and it goes straight up and down.

Kat DeLorean: Do you think that with the advent of technology, we’re going to lose some of what is gained by somebody like you who has all the knowledge because you understand the process so intimately? We as humans can put together much more disparate information than a computer because the computer has to be told to do so.

And from what you’ve been describing and from working with you, it seems as though these new simulators are going to actually start to cause some loss of innovation in this process because the masters will no longer be able to pull a car apart in their head. And figure out how to do it better.

Tony Vallelunga: Exactly right.

Yeah. Kind of like learning math. We didn’t have calculators years ago. You had to learn and just do it. So once you get a calculator, well you [00:19:00] lose the ability to learn your math skills. It’s the same thing with simulators. You need to learn hands on to really get a grasp on it. These simulators, they’re just aids.

But yeah, same thing. If you have it, then you rely on it as a crutch, but it’s a help. It’s a tool.

Kat DeLorean: There’s some value in what’s learned when you have to work through troubleshoot things. My experience working with Tony, he’s able to come up with some of the most fantastic ideas and thoughts just out of the blue, because you’ll start talking about some component of the car and.

Hearing him describe it, I can now picture every conversation that he was picturing everything in his head and picking it apart. Just listening to this conversation, that’s a masterful skill that has to come from years of troubleshooting. Tony has talked about just some of the ways that he’s been able to innovate.

Solutions that I think have led to somebody who can understand how to change things and bring you to a new way [00:20:00] of doing it.

Tony Vallelunga: Oh, yeah. You have a saying you learn by doing.

Kat DeLorean: Yes.

Tony Vallelunga: Throw you to the wolves and you go to work, figure it out. Because if it’s not you, who else is it going to be?

Kat DeLorean: Tony’s going to teach me how to do it all, including forging and fire, because now everybody in the world wants to do that.

And Tony’s going to teach us.

Crew Chief Eric: You can thank History Channel for that.

Kat DeLorean: Yeah.

Tony Vallelunga: You don’t want to be doing a blindfolded before you know it.

Crew Chief Eric: Let’s rewind the Wayback Machine for a moment. What was one of the most challenging things for you as the tool and die guy on the DMC 12? Was it the gullwing doors or was there something else about the original car that posed, you know, a challenge that you had to kind of adapt and overcome to?

Tony Vallelunga: Uh, the doors were the most challenging. The hood’s flat. That was the easy part.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, isn’t there all controversy over that too, depending on when it was built, the hoods are actually different, or so you guys change something, flap or no flap, I lose track of it. Right, so

Tony Vallelunga: we call those engineering changes [00:21:00] or developments along the way.

So yeah, those are the things we do, right? We either put a flap in or no flap.

Kat DeLorean: When the incremental changes are made, On modern cars on the DeLorean, what happens to the old dyes? Are they able to be modified to be repurposed? Are they just gotten rid of what happens to them?

Tony Vallelunga: No. So small changes, we can modify the diet.

It’s fairly easy. Yeah. There’s no reason to make for a small change to make a whole new bag. You know, not unless you have a radical change where it makes sense

Kat DeLorean: when they get rid of a model year. So the Corvette, you know, see it. So C7. Body dyes, what happens to those, do those get destroyed so that nobody can make them or do they get sent to somebody who can then continue to make them after market?

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, what happens to the old body dyes is they still have to make replacement parts for 10 years afterwards. So for replacement parts, usually before the end of the run, they’ll try to stock up the [00:22:00] warehouse. For service parts, but after that, they’ll have a another company just run service parts. That’s all they do.

They’ll just run service parts for the 10 years for whatever, you know, damage rust. And that’s the way it is after the 10 years. Well, I’d have to say, what’s the demand of the vehicle, right? Perfect example, 55 through 57 Thunderbird. I had worked for the bud company in Detroit in the late 80s. The Thunderbird Club bought and stored the dyes there, and we ran replacement parts in the late 80s for the 55 through 57 Thunderbird.

So, It depends on the demand. So you think maybe you just have to run service parts for 10 years, but that’s not always true, depending on the demand of the vehicle. Of course, DMC is one of them, right? We still need replacement parts 40 years later. So it just depends. But for the most part, they usually have to run service parts.

Crew Chief Eric: Notice he said nobody kept the 58 to 60 square bird dies though. They were like, no, we’re [00:23:00] putting those in the ocean. Nobody wants parts for those

Tony Vallelunga: supply and demand, right?

Crew Chief Eric: Tony, you’ve had a very extensive career in the automotive industry. And like you said, you met John at MSI and, and, you know, you worked at DMC and everything else, but you also found yourself at Chrysler for a long time.

Tell us about some of the cars you worked on. Some of the things that we would notice right away and go, that’s. Car that Tony V built the dyes for. It

Tony Vallelunga: wasn’t all me, right? It was at this point, you know, it’s the company, right? But what I was involved in at Chrysler was the Ram truck, the Dodge Dakota, Jeep Grand Cherokee, Chrysler’s minivan.

And. Part of the regular Cherokee. I had covered all those vehicles.

Crew Chief Eric: I thought you were gonna say like Aries K car, but no, that’s

Tony Vallelunga: Well, you know We did do some stampings for those, right? Well, it’s all good.

Kat DeLorean: Did it Mike work on parts for the Viper though?

Tony Vallelunga: Oh, absolutely. [00:24:00] Yeah He had a little different career than me.

He just stayed

Kat DeLorean: there

Tony Vallelunga: for 40 years and he got the chance to do all the exotic vehicles. Mike, I got to work on the, uh, Ford GT, custom made panels, right? Heaton wall for some of those shapes. He also worked on the Viper. And numerous other vehicles,

Kat DeLorean: Mike is the other gentleman on our team who works with Tony in Detroit, who also worked on the first cars that were built in Detroit.

Tony Vallelunga: Yeah, both Mike and I worked on the DMC together.

Crew Chief Eric: Were you in Ireland then with everybody else?

Tony Vallelunga: No, no, no, no. Everything that all that was done in Detroit.

Crew Chief Eric: And then shipped overseas for assembly.

Tony Vallelunga: Yes, so what happened was the prototype dies were done here in Detroit. And the prototype build was done here in Detroit.

Kat DeLorean: The first 500 cars were actually manufactured here in Detroit with the prototype dies. That’s the story that I’ve been told about.

Tony Vallelunga: So basically the first 500 were done in Detroit.

Crew Chief Eric: Interesting. [00:25:00] So do they still exist? Cause I’ve heard things about the VIN numbers. Don’t start at one and all that kind of thing.

Tony Vallelunga: That part of the story. I don’t know.

Crew Chief Eric: Cause there are the other, the early, early variants. Even there’s the pictures of your dad with Jujaro with the JZD and then the DSV that preceded it and all that kind of stuff. I wonder where those cars ended up. Are they in a museum somewhere? Are they locked in a crate, like, with the dyes?

Kat DeLorean: What’s weird is that I know that my dad had six. That were on our farm in New Jersey. I have a photograph.

Tony Vallelunga: The Peterson Museum has one of their prototypes, don’t they?

Kat DeLorean: There’s Proto 1 and then Proto 2, but there’s also another prototype car that to some extent exists. But the first 500 DMCs, it’s very interesting because you’re not the first person to ask, where are these cars?

Where are these cars? And I have no idea. This is a new mystery that’s turned up. Maybe somebody knows.

Crew Chief Eric: Maybe it’s like when you get a checkbook for the first time [00:26:00] and they ask you what number you want to start at and you just go from there.

Tony Vallelunga: I believe historically they either used the prototypes for crash tests, maybe they weren’t so called street legal at the time, maybe they have to destroy them.

Kat DeLorean: That’s a good point because a lot of the cars were crashed for crash tests. It could be that a good portion of them were crash tested. It could be that the early cars to belong to special enough people that they’re locked away. Yeah, somebody’s really special collection. Yeah, we just don’t know. But it’s definitely a question that has come up quite a few times during this journey.

What happened to your dad’s cars? And what happened to the early cars? And why does it bins all weird? I don’t know. Hopefully we’ll find out.

Crew Chief Eric: You’ve had a, again, a long, illustrious career working in different organizations within Motown in Detroit, and now you find yourself as the Senior Director of Manufacturing and Quality for DNG.

So, what are you thinking? This is [00:27:00] huge.

Tony Vallelunga: Way huge. Way huge. I am so honored to be working with Kat and Jason. and everybody on the car. It’s such an honor. I’m excited. I’m ecstatic. There’s no words to describe it. Grateful. Something I’ve always wanted to do. Whatever I could do to help, because what John has done for me.

Crew Chief Eric: I think a lot of people might be thinking, well, manufacturing and quality, that’s, that’s like after the fact, right? Especially the quality part, but you’re involved. In the process right now, right alongside Angel, who’s refining the design. Everybody else is getting involved, you know, in this massive circus.

That is what car companies are, right? Like we talked about in the intro, it’s so many people to make this happen. So what are you thinking about? You’re obviously interfacing with a bunch of people. What have you suggested? Any changes yet? You know, other things that are on your mind about the new design.

Tony Vallelunga: The new design in my head, I want to make exactly. As [00:28:00] Angel would want the best of my ability and we’re going to give them if we have to change something for a reason, we’re going to talk about it and tell them what I see fit for a form or how we’re going to match up a door to a quarter panel. Or a hood to a fender or vice versa.

That’s what we go through, right? But we want to try to give Angel exactly what he wants, what he’s looking for.

Crew Chief Eric: So have you already started putting together the prototype dyes yet? And I guess the question that we didn’t ask that goes along with that, how long does it take to construct a dye?

Tony Vallelunga: Well, that’s a huge question.

Usually once we get the green light to go, three months.

Crew Chief Eric: And that also depends on the material you’re making it out of.

Tony Vallelunga: Yeah, it depends on the material, right? We’ll have to tune it in to the type of material we use, but the shape will generally be the same. We’ll just need to process a little bit.

Crew Chief Eric: If the [00:29:00] decision gets made to go 100 percent stainless again, do you see anything getting in the way of making that successful?

Or has the manufacturing process for stainless changed? Enough in the last 40 years that it’s it’s just like anything else

Tony Vallelunga: when I first saw the new car design. I pictured everything in stainless and what it would take to make it work. If you could do that in stainless, you can make it out of anything after that.

Kat DeLorean: So this is actually a great time to talk about some of the challenges that arose trying to make the car out of stainless. So we have a couple of different things that we need to address. In creating a car in a company, there’s a whole order of operations that you go in, which was blown away by everybody coming and saying, here you go, let’s skip all the steps.

We have a situation where we have a lot of things before most people normally would, including the whole team of Incredible people [00:30:00] and actually an engine and all sorts of things that we shouldn’t have at this point. One of the things that posed a really, really critical challenge was making the car out of stainless steel, the funding that’s required to do so.

And the challenge of working with the metal in the time that we have to actually build a show car, we are working to address a lot of different things in how we actually manufacture the car out of stainless. And one of the challenges that I’ve given my team is. My father is not the only person that I need to honor in making this car.

It’s also the people who’ve kept his legacy alive all these years. So it doesn’t matter if John would have made it out of stainless today. It has to have stainless to honor the people who really want to see it in stainless. But given what we have available to us today, can we leverage what new technologies, new ways of manufacturing new ideas?

That we can use to make it lighter because the stainless car is heavy. So what can we do to actually manufacture it and still maintain that look and [00:31:00] then have something that’s lighter. A lot of the ways that we’ve come up with, they either work or they don’t. One of the other things that is important to address is the positive intent of the stainless.

which was to make it cost effective for the owner to maintain. So if we can’t make it out of a solid stainless panel for whatever reason, what can we do to honor that aspect? How do we still make it look the same, have the same stylistic aspects to it and be able to meet the challenges. And as we go along, we’re taking notes of the changes and the things that we have to do because it allows us to address the questions such as.

Why does the DeLorean have a Renault Tension? There are reasons for these things. They all have to do with the challenges that we’re currently facing and trying to manufacture this car exactly the way my father did. Tony has been incredible coming up with some really unique out of the box ways that we might be able to actually build this car and keep it 2, 500 pounds instead of 3, 200 pounds, make it actually go really fast and handle very [00:32:00] well.

Tony Vallelunga: If that comes under advanced manufacturing, I would say.

Kat DeLorean: Yeah. It’s been a lot of fun, though, because what we also get to do is think outside the box and brainstorm some pretty crazy and fun ideas, and these guys are brilliant, and I’m having the time of my life learning things I never thought I didn’t know about making cars.

Tony Vallelunga: Well, now’s a perfect opportunity. Time to do this right now, right? So it’s fabulous.

Crew Chief Eric: If you look back in automotive history, we’re sort of repeating ourselves in a way, not necessarily the DeLorean story. What I’m getting at is if you look at the 1920s versus the 2020s in the original twenties, there were all these boutique manufacturers.

And you see it now with the rise in the advent of EVs. Every time you turn around, some new company is developing some alternative fuel vehicle, whether it’s electric, hydrogen or otherwise. And then eventually the market course corrects itself and they get absorbed by the bigger [00:33:00] companies just like they did back then.

The truly inventive survive, right? And then they flourish from that point. I see that. With this car in a lot of ways, and all the things that have been privy to thus far, you know, the kind of out of the box thinking and revolutionary ideas. I think you guys are the pointy end of the sphere when it comes to some of these techniques.

I’m really curious to see how it plays out because. The engine packaging alone makes a huge difference on the body panels themselves because internal combustion engine or a hybrid even for that matter, you don’t have to worry so much as like a negatively charged body like you would end up with an EV.

And then you have issues with if it wasn’t in stainless steel with the painting process and even the Let’s say the car care application process, you have to get specially manufactured waxes and things to work with EVs. A lot of people don’t realize that when they buy a Tesla or Lucid Air or something like that.

So to your point, Kat, there’s so many different pieces of this down to the, how do we do the [00:34:00] LEDs and the brake light to how do we keep it light? How do we make the Bonnie panels and all that? And I think there’s some compromises out there. We talked about this it’s like maybe a composite material, something space age.

Something that hasn’t been thought of before.

Kat DeLorean: There is a huge challenge with building a car in Detroit, which is what we’ve promised and what we are working to do. I want to manufacture it there because I want to be able to give work to the people who are there, which is more important to me than the building of the car, but when you have people who can hand build the car.

Out of composite materials and produce the same car without actually having to build any dyes and you can save money like that. You have an opportunity to produce something that you can actually show people while you work on the manufacturing process. Because you do have to build those dyes. And one of the ways that we’ve been talking about is if you hand build the car out of composite, the stainless panels become something that is much more of a challenge [00:35:00] because then they would have to be hand formed for the car.

That’s a little Pagani area for me when it comes to the price of the car. And I love those cars, but I’d like to not have mine cost that. One of the things that I asked was specifically, can we get a wrap? I was told that that would not translate. white as well. But we are looking into an alternative way to actually create that thin sheet of metal to go on top.

One of the problems that that has is it becomes merely a stylistic component. And then we have the aspect of the body panels could end up in a landfill because they can’t be recycled and broken back down. If we cover the composite with the metal, how can we then recover the materials from it and turn it into something that matches my father’s positive intent?

Because Part of the reason why the panels weren’t stainless was so that they could be sent back to the factory, melted back down and body panels made from crashed cars, making it incredibly cost effective for the owner to actually own. [00:36:00] Now, all of these things are next to impossible to implement into a one off prototype.

So having something that’s going to be affordable in a prototype is not a realistic thing. But we’re using this whole process to find out how do we reduce the cost of manufacture? What materials can we use? What processes? How can we distribute the manufacturing to actually bring the cost down by simply going to unique places never thought of before?

How do we create a new way of doing it and a new way of building the car where we can give both the people what they want and still be able to meet these challenges. If I fail, you’ll know why I failed and how I failed and what needs to be done differently in order to succeed next time. But we’re going to have a car, it’s going to be amazing.

And It better be stainless steel of some kind.

Tony Vallelunga: Yeah. And we’ll get it. Not a problem.

Kat DeLorean: The fun part’s going to be [00:37:00] everybody being able to learn a little bit more than they ever knew before about how this all goes down, because we’re going to take everybody along with us and explain what’s going on to tell my father’s story.

So

Tony Vallelunga: that’s the fabulous part about this, bringing people on board and collaborating different stories together, right. And learning from one another. Extremely happy to be part of this, ecstatic. It’s going to be a great venture.

Kat DeLorean: The way that we’re working together, from what I’ve been learning about how everything’s always been done before, it’s truly a unique experience.

And the way that we’re going about it, the way that everybody has come together to do this, the collaboration, the minds. The people who’ve come forth to participate have astonished me. They’re truly geniuses together. We are definitely my father’s mind. I can tell you that much, which is saying a lot.

Tony Vallelunga: Thank you for orchestrating all this, right?

Kat DeLorean: No, you all found me and said, let’s build a car. And all I’m here [00:38:00] is. To be the person to run the meeting is really all I do. I guess that’s what a leader’s job is. Is to let their people do exactly their great stuff. They truly are remarkable. And I don’t think anybody has ever had this much fun building something as stressful as a car company.

Tony Vallelunga: Well, we try to keep it fun as much as we can, right? There’s a serious side too to it, but we have fun along the way. For sure. I just love collaborating on different ideas all the time. It’s just fabulous. CAD has me really thinking outside the box when it comes to creative and manufacturing.

Crew Chief Eric: With your experience in the industry, I mean, obviously you’re bringing that to the table, which is…

To cat’s point, kind of shortcutting the process and there’s a lot involved in this, but you’re passing that knowledge on right? Rather than us going, how do we use a simulator to make this work? But there’s the other side of the paradigm here, which is the stem program. I [00:39:00] want to address your involvement in that and how you take everything that’s in your.

Vast experience and translate that down to high school and college kids that don’t know a spanner from a wrench at the end of the day. So how are you planning on turning this into an educational moment for them?

Tony Vallelunga: See what their knowledge is at the time and keep it simple enough. To where they understand it and run with it from there.

Crew Chief Eric: So are you going to have them maybe building scaled versions of the dies and stuff to stamp out like smaller models?

Tony Vallelunga: We can do that. Yes, absolutely. 1

Crew Chief Eric: 18th scale, please. That’s, that’s all I’m going to say about that.

Tony Vallelunga: So, you know, what was funny when Kat and I first met, we got on a conversation to ask, can we source some fenders or parts out of stainless?

And my first question is, sure, how many you want? Uh, then it turned into building a car. Okay, then I, I [00:40:00] said, okay, how many you want? Just having that knowledge and to be able to pass it on to somebody. For me, it would be easy, right, but to explain it to somebody, and they can, a person can only grasp so much knowledge at once.

So, you have to be careful and keep it simple in the beginning and work with it and go from there. Once you know the whole process, it’s… Fairly fundamental. It just depends on a person and how fast it clicks.

Kat DeLorean: My experts that I have, what I’ve been asking them along the way is for what I like to call how to put on your socks.

Jason told me about a basketball coach. Who would have his players put their socks on correctly with the seam in the correct place because then they could play longer without their feet hurting. So what we want to do is what are those fundamental things to think about and teach and create muscle memory for What will create a good [00:41:00] manufacturer or a good engineer?

And so each of my experts in the field, particularly useful are people who have that knowledge prior to simulators, it seems, what are the things that we could have the students do that will form this fundamental knowledge that can then be built upon when they go into the job space and create somebody who has a stronger foundation to be able to learn it faster.

And Dan Milliman, in his book, The Complete Warrior’s Way, he was a coach of gymnastics. And he said, he sees natural talent as the ability to learn something faster, not the ability to learn something better. It’s just that other people need more time. To be taught it. So if we can bring people up to that base level by giving them the exercises and the foundational knowledge they need to be able to learn it on the job, just as fast as everybody else, or send them with the skills to know how to ask for what they need to be able [00:42:00] to get what they need to learn it.

The way that everybody else does, then we can create people who can just excel and enjoy what they’re doing. I’ve been working a lot, asking a lot of questions and Tony helped me very early on to map out some of the classes we have. The vocational schools, they start a little earlier in Detroit, but most schools, you can’t take auto shop until junior year.

We want to have something that can actually work with the other teachers and be able to tie their knowledge in their automotive program to other subjects. For instance, How did World War Two impact the automotive industry so that you understand how that happened or what can you learn about your customers in sociology and how that can impact how you design a car because you understand more about humanity, everything that we learn.

As we’re out there experiencing the world, every subject that we take pertains to what goes into automotive design. Because it’s all about the people, the [00:43:00] marketing, the build, the manufacturing, the safety. All of these things have components in all of the subjects we learn. So how do we teach them to think about all of it and put it all together in the end?

And that’s where my experts come in. But I’ll tell you a secret. We are working on virtual reality manufacturing labs. For the students to be able to practice some of these skills and immerse them in things that they normally wouldn’t be able to experience due to safety or location, fun story. I go to a car show in celebration, usually in the spring.

I haven’t gotten since COVID, but it’s an amazing car show and they raise money for make a wish. And I got to meet these two wonderful people, Douglas Saunders and Nick Kambata. They’re just. incredible and so much fun and we’ve become really good friends over the years and they’ve been working on this incredible virtual reality platform that they’re focusing on for what it’s designed for now.

But I said, as we go and build this out, would you consider [00:44:00] working on a virtual reality lab? Hopefully we can make that a reality too, because that would expand access to this knowledge to so many more students. And that’s what we’re trying to do.

Crew Chief Eric: Nice, obviously the program is going to be limited in the number of people that we can put in the seats in the DNG STEM program for the listeners out there, or maybe even folks that are in the industry right now, I happen to know a few myself, any words of wisdom, anything you can pass on to them, maybe some lessons learned in the field that you’d like to share with these folks as well.

Tony Vallelunga: The biggest thing is giving the opportunity to do it. Giving the opportunity in working with a group of people and bounce out ideas off one another is just how it’s done. Pass this knowledge down to everybody we can, to the next generation. What I’m going to enjoy doing. I can eat meat.

Crew Chief Eric: The DeLorean Legacy Project is dedicated to extolling the positive impact of John Z.

DeLorean and his [00:45:00] creations on this world, that continue to this day through the fans and owners of his cars. The DeLorean Legacy Project’s mission is to change the world one person at a time. To learn more about the project, check out www. deloreanlegacy. org Or follow them on social at DeLoreanLegacy on Twitter.

You can catch up with Kat on social media at Kat DeLorean on Instagram at Katherine. DeLorean on Facebook. And you can learn about this stellar new cutting edge technology DNG Motors vehicle in Inspired by Angel, Tony, and a cast of other folks at www. dngmotors. com or follow the cars build progress at dng.

motors on Instagram and Facebook or at dngmotors on Twitter. So Tony, I can’t thank you enough for coming on Brake Fix and sharing your wealth of experience with us, talking us through the old days of both the DMC 12 and the heyday of Motown, sharing some of your [00:46:00] insight on how the new car is going to be built.

So we’ll be keeping up with you and watching the progress. And I think all of us are saying the same thing. We can’t wait to see this thing in person.

Kat DeLorean: I’m going to always thank my team, including you, Eric. Without you guys, I could definitely not be doing what I’m doing right now. I am only as good at this as all of you are helping me be, so always and always, thank you.

Tony Vallelunga: Yeah, thank you. Thank you. Again, it’s everybody involved, right? Extreme cooperation is just fabulous. Thank you for having us. Thank you for hosting us. We’ll be talking again, right? I can’t wait.

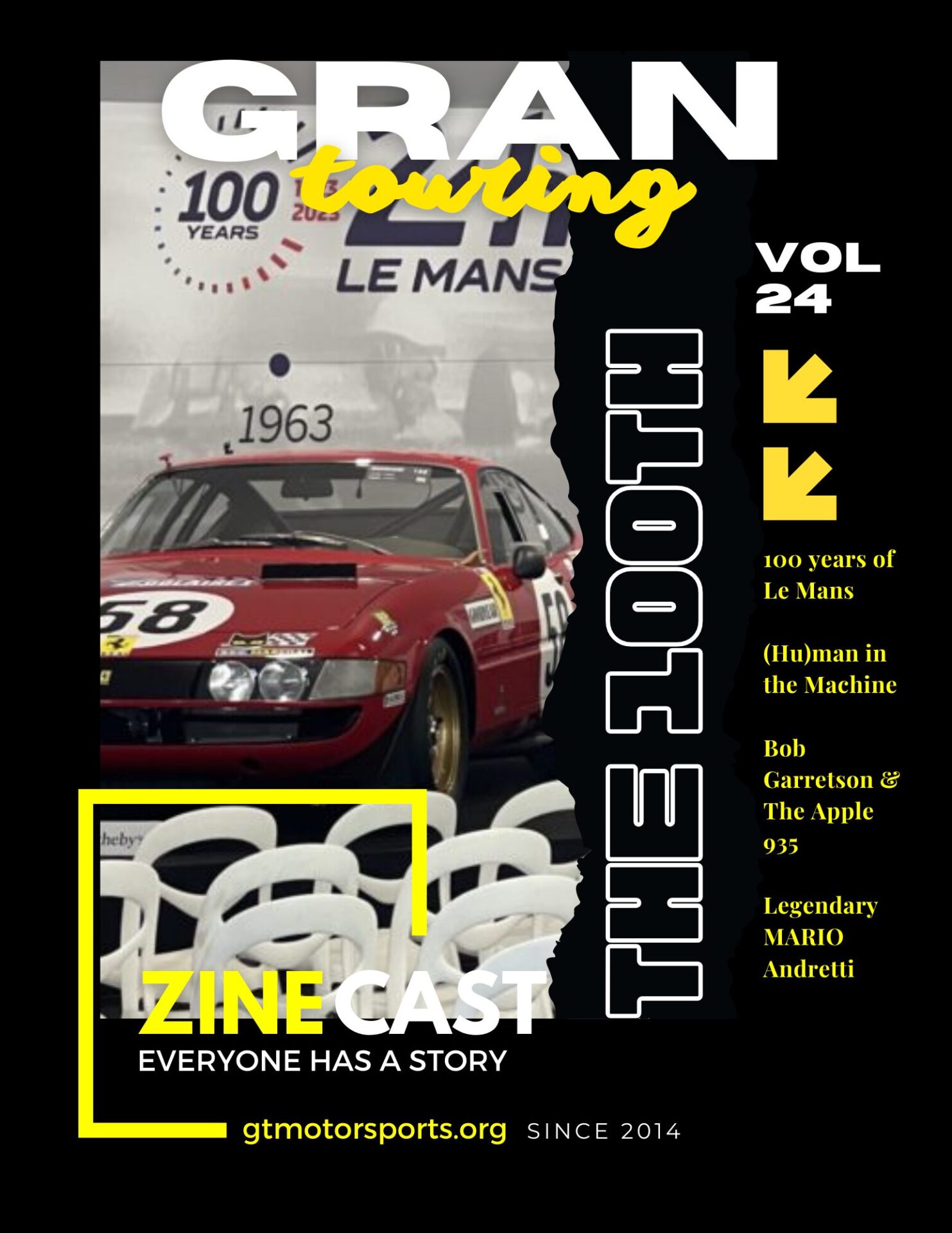

Crew Chief Brad: If you like what you’ve heard and want to learn more about GTM, be sure to check us out on www. gtmotorsports. org. You can also find us on Instagram at Grand Touring Motorsports. Also, if you want to get involved or have suggestions for future shows, you can call or text us at [00:47:00] 202 630 1770, or send us an email at crewchief at gtmotorsports.

org. We’d love to hear from you.

Crew Chief Eric: Hey everybody, Crew Chief Eric here. We really hope you enjoyed this episode of Break Fix, and we wanted to remind you that GTM remains a no annual fees organization, and our goal is to continue to bring you quality episodes like this one at no charge. As a loyal listener, please consider subscribing to our Patreon for bonus and behind the scenes content, extra goodies, and GTM swag.

For as little as 2 and 50 cents a month, you can keep our developers, writers, editors, casters, and other volunteers fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster. Consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without fans, supporters, and members like you.

None of this would be [00:48:00] possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Meet Tony Vallelunga: A Journey in Automaking

- 02:06 Early Influences and Education

- 03:23 First Steps in the Automotive Industry

- 04:12 The Art of Tool and Die

- 05:52 Challenges in Manufacturing

- 10:20 Innovations and Modern Techniques

- 14:24 Reflections on the DeLorean DMC 12

- 21:34 Body Dyes and Replacement Parts

- 23:06 Tony’s Career Highlights

- 26:46 Manufacturing the New DMC

- 28:59 Challenges with Stainless Steel

- 34:14 Innovative Manufacturing Techniques

- 38:52 STEM Program and Education

- 44:53 The DeLorean Legacy Project

- 45:48 Closing Remarks and Gratitude

Bonus Content

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others by way of Break/Fix and GTM. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

|  |  |

Learn More

Tony’s Bio

I worked at the prototype house where the DMC-12 was built. We were not allowed to talk to the customers and if so it had to be brief, and it was for safety also, I was running at the time was on state of the art new 1200 ton hydraulic press, the largest press in the plant, it was our job to take a new development dies and make it work in the press to make parts, in which it can take days to make it work, but remember we had more than one vehicle we were working on, you know some might say it was just another car that came through the plant, but we all knew it was John DeLorean’s and it was a gull wing car done in stainless steel, we all knew John’s history before he came in and how famous he was in the auto industry, so yes it was a big deal at the time, we knew he was coming through the plant, we had everything clean and somewhat staged at the time for John’s walk thru, we all knew at the time that John had some ties to the prototype house because there were four engineers from General Motors who owned the place, so here I am working on a press operating it and here comes John along with two other gentleman walking down the aisle way, at the time we all knew who John was we didn’t know who the other two gentlemen were, I have to assume one was Barry, but I didn’t recognize him at the time, and I don’t know who the other gentleman was, but I remembered John was in the middle obviously was the tallest and the other two gentlemen we’re on each side of him, for me and I have to assume others at the time, it was like the president of United States walking through, yes It has left a lasting impression in my mind that I will never forget, but I knew after that my career was set for life, I knew I always had that experience in my back pocket for the rest of my life, at the time it wasn’t the only stainless steel product that we made there we made gas tanks out of stainless steel also, so after that I worked in various small job shops chasing the dollar, then finally I caught a break I was hired by the Budd company in Detroit, at the time they had the largest presses in North America, they were a high-volume supplier to the big three, and I ran the two largest press lines there, The budd company was where the original Hupp mobile was built in early 1900s and the 55 through 57 Thunderbird body was built there and assembled, the thunderbird club had bought and stored the dies there and while I was there we ran replacement panels for that vehicle what an awesome job at the time to to be able to experience that, then there was a large turnover at the big three for Die Maker’s at the time, and some of us were heading out the door for more money and still being able to be in with the UAW, General Motors and Ford were picking us up as engineers and Die Maker’s Chrysler was just picking us up for the most part as Die Makers so I picked Chrysler because it was close to home, and the rest is history.

To learn more be sure to check out www.deloreanlegacy.org or @deloreanlegacy on Twitter. You can catch up with Kat on social @katdelorean on IG, @kathryn.delorean on FB. You can learn all about new DNG Motors vehicle inspired by Angel’s design at www.dngmotors.com or follow the cars progress @dng.motors on Instagram/FB or @dngmotors on Twitter

Now at DNG Motors, Tony is helping bring the next DeLorean to life. Working alongside designer Angel Guerra and Kat DeLorean, he’s applying decades of experience to modern challenges. From clamshell hoods to reverse-popping designs, Tony sees the car in exploded view – envisioning dies, press angles, and material behavior in real time.

Simulators vs. Experience: The Human Touch in Manufacturing

While draw die simulators offer 80% accuracy, Tony warns against overreliance. “You learn by doing,” he says. His ability to mentally deconstruct a car and foresee manufacturing hurdles is a skill honed through years of troubleshooting – not something easily replicated by software.

Tony’s passion extends beyond the factory floor. He’s helping shape DNG’s STEM initiative, aiming to teach students not just how to build cars, but how to think like manufacturers. From virtual reality labs to foundational exercises, the goal is to create muscle memory and intuitive understanding – skills that simulators alone can’t teach.

Honoring Legacy Through Innovation

Kat DeLorean’s mission is clear: the new car must honor her father’s legacy and the fans who’ve kept it alive. Stainless steel isn’t just a material – it’s a symbol. But with weight, cost, and sustainability challenges, the team is exploring composite materials, recyclable overlays, and advanced manufacturing techniques to preserve the look while improving performance.

Tony’s story is a full-circle moment. He helped build the first 500 DeLoreans in Detroit, and now he’s helping build the next. Whether it’s stamping out Ram trucks, Vipers, or the Ford GT, his fingerprints are on automotive history. And with DNG Motors, he’s ensuring the future is just as bold.

Guest Co-Host: Kat DeLorean

In case you missed it... be sure to check out the Break/Fix episode with our co-host. |  |  |

The following content has been brought to you by The DeLorean Legacy Project and DNG Motors, Inc

|