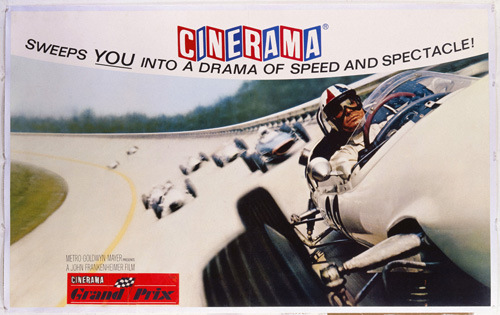

Grand Prix stands as a dramatized snapshot of Formula 1 in the mid-sixties. Director John Frankenheimer chose to film real Grand Prix in order to capture the right level of drama and speed, and in so doing produced an amazing document of the 1966 season. It is important that all of the things which happen in the film happened in real life at some time, from crashing into the Monaco harbor, to Ferrari drivers mysteriously left waiting in the pits without a car to practice in for the imminent Grand Prix with, in order to put just a little more psychological pressure on them to go out and prove themselves when – if – the car did arrive*.

To modern eyes, the plot is rather slow moving and schmaltzy, even contemporary reviewers criticized this aspect of the film, but what is captured very well is the notion of the Formula 1 circus, a wonderful and spectacular show which descends on a town, transforms it for a few days and leaves again, like a medieval itinerant monarch. That the season, beginning in the spring sunshine at Monaco, and ending in the September flat out blind at Monza, and the World Championship is the timetable around which all else – engineering, finances and personal relationships – are structured. That the reason men race is for honour and glory, because something inside them compels them to do it, nothing at all like NASCAR where everyone involved has always been there to make money.

The danger aspect may seem overplayed and melodramatic, and perhaps it is, but the fact remains that in that era a Formula 1 driver was statistically more likely to end his career with a fatal accident than retirement. Indeed, this danger was what attracted drivers, and spectators alike – it was this which prompted Hemingway to comment “there are only three true sports – bullfighting, mountain climbing and motor racing; the rest are merely games”.

Indeed, it is that ability in competitors to face danger and stare it down which holds my attention with old fashioned motorsports.

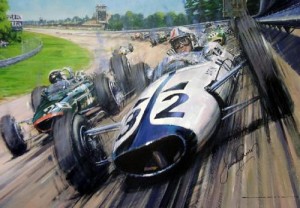

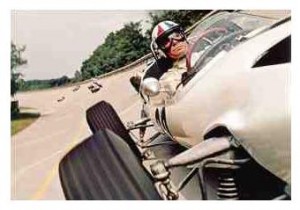

One of the best facets of Grand Prix is the clip above – the coverage of the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa. It was a wet race – a theme at Spa. The other theme at Spa is fast, sweeping corners – the average lap speed was more than 140 mph in 1966, this on closed public roads, at one point featuring a flat out left right kink between two dry stone walls – a small farm, in fact. Using then cutting edge film techniques – helicopters, camera cars moving at racing speed – Frankenheimer captured and wove into his film a race which developed into a terrific duel between emerging talent Jochen Rindt, and Ferrari’s John Surtees. Surtees, the eventual winner, sticks in the mind today because he is famously the only man ever to be World Champion in a car and on a bike. When I saw his car at Pebble Beach last year, alongside his MV Agusta Grand Prix bike, I was thinking of Frankenheimer’s film, and moreover the Spa coverage – that is to say, more than forty years on this remains some of the most compelling and memorable motor racing porn you will ever see.

The Monza sequences too are spectacular, featuring cars racing on both the traditional flat road course and the steep Monza banking, complete with the car breaking bumps and even a car leaping over the top – the result may be dramatized, but it still gives a wonderful sense of what racing in 1966 was really like.

Grand Prix is also compelling for the men who appear in cameo. Juan Manuel Fangio, Jo Bonnier, Bruce McLaren, Ritchie Ginther and Jack Brabham each appear in various scenes – a post race party at Monaco, the driver briefing at Clermont-Ferrand – so many drivers in fact that they run to two screens worth of names in the credits. Phil Hill and Graham Hill play characters with a few lines, often amusing given the characters of the men themselves: Bob Turner ( G Hill ) is a key ring leader in drinking games and beer throwing is victory celebrations, while Tim Randolph ( P Hill) comments “anyone who is that nervous should take up another profession” ironic given what a worrier Hill himself was.

In the scene introducing Eva Marie Saint, Ferrari driver Lorenzo Bandini can be seen standing behind her – the director’s classic technique of filling the backshot with beautiful people. Bandini’s involvement is blackly ironic given that two years after filming he would crash injuring himself fatally at exactly the same point on the course where characters Pete Aron and Scott Stoddard crash during the film.

A key, and I have to say rather hammy plot device is to have characters almost directly translatable to real characters in the pit lane, although only a few names carry over – BRM, for example, and the only irreplaceable thing about Formula 1, Scuderia Ferrari (originally Ferrari did not want to participate, since racing films are generally so lame. Frankenheimer visited him after the filming of Monaco, and showed him what he had; impressed, Ferrari agreed to be involved). Character Scott Stoddard when injured recuperates at his home, a farm, and wears a tartan flat cap such that one cannot mistake Jim Clark; his helmet too has a tartan band, like Jackie Stewart’s, allowing for good continuity between scenes of Stoddard racing and the real race film of Stewart. Scott is fixated on his brother, Roger, continually trying to outdrive him although he is dead and gone. We see Roger in portrait – he is an amalgalm of Stirling Moss and Mike Hawthorn, blond and flat cap driving Moss’ Vanwall. Scott makes an improbably swift recovery from his near fatal injuries, seeming to use plenty of good old fashioned British pluck and not much else – in a manner similar Stirling Moss, or Graham Hill. Stoddard’s team leader is meant to represent Lotus’ Colin Chapman, while the Japanese Yamura corporation clearly represents Honda’s mid-sixties Formula 1 involvement; in that blend of Yamaha and Honda’s later Acura brand, there is a sense life is imitating art ! Like John Surtees, the character Nino Barlini is a champion motorcycle racer looking for a fresh challenge racing cars.

More than this direct translation, there are many details lifted straight from the real world of Formula 1 onto the silver screen: the other drivers discuss Sarti in the same way as contemporary drivers felt about Fangio; when Aron and Stoddard crash at Monaco they have committed the ultimate sin, since they are teammates, and thus not meant to be racing with each other, and their team owner is furious as a result, firing Aron; Sarti himself has a picture of Guiseppe Campari on the wall of his “little place at Monza”; it was Campari’s death at the Italian Grand Prix at Monza which lead to the black flag being shown to the remaining Ferrari team cars and their withdrawal from the event, events which play out again at the climax of “Grand Prix”.

The net of all these real life elements is unexpected and unfortunate – the script is wooden, and the characters somewhat two dimensional; it is rather strange that real people make such unconvincing movie characters !

Aside from the poor script, perhaps the reason the characters are unconvincing is Hollywood’s need to show audiences a familiar, well loved tale – the so called “five act structure”. One of the key plot lines in Grand Prix is Sarti’s growing relationship with Louise Fredrickson, ( Eva Marie Saint) a fashion writer seeing Formula 1 for the first time – a cunning device allowing the film makers to introduce the audience to Formula 1 through Louise . As he falls in love, Sarti re-evaluates his life, and takes a decision to retire – the outlaw gunfighter who’s decision to live in a less dangerous way is triggered by the love of a Good Woman, common to a million westerns. More painful to watch are the scenes concerning Scott Stoddard’s relationship with his wife – a mid sixties take on “modern values” which has dated as badly, but nowhere near as humorously, as the spinning tapes and flashing lights of “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century”:

It seems that film makers need to decide if they are out to make a film about cars and racing, or a film with some appeal for non-car people. In his attempt to compromise, Frankenheimer fails on the human interest side. It is interesting to note that Steve McQueen was Frankenheimer’s first choice to be Pete Aron. However, negotiations fell through and McQueen set out on the road to make Le Mans. More even than Grand Prix, the character elements of Le Mans fail, and indeed the producer left during filming because no script could be agreed upon, and by implication he had despaired of being able to make the film commercial – that is to say approachable for non-car people. Having said this, Grand Prix benefits enormously from Hollywood’s glossy high production values; the art work of Campari and Roger Stoddard are Michael Turner originals and the film won three Oscars, one for cinematography. The opening sequence, by Saul Bass received particular acclaim:

There’s a higher resolution version here.

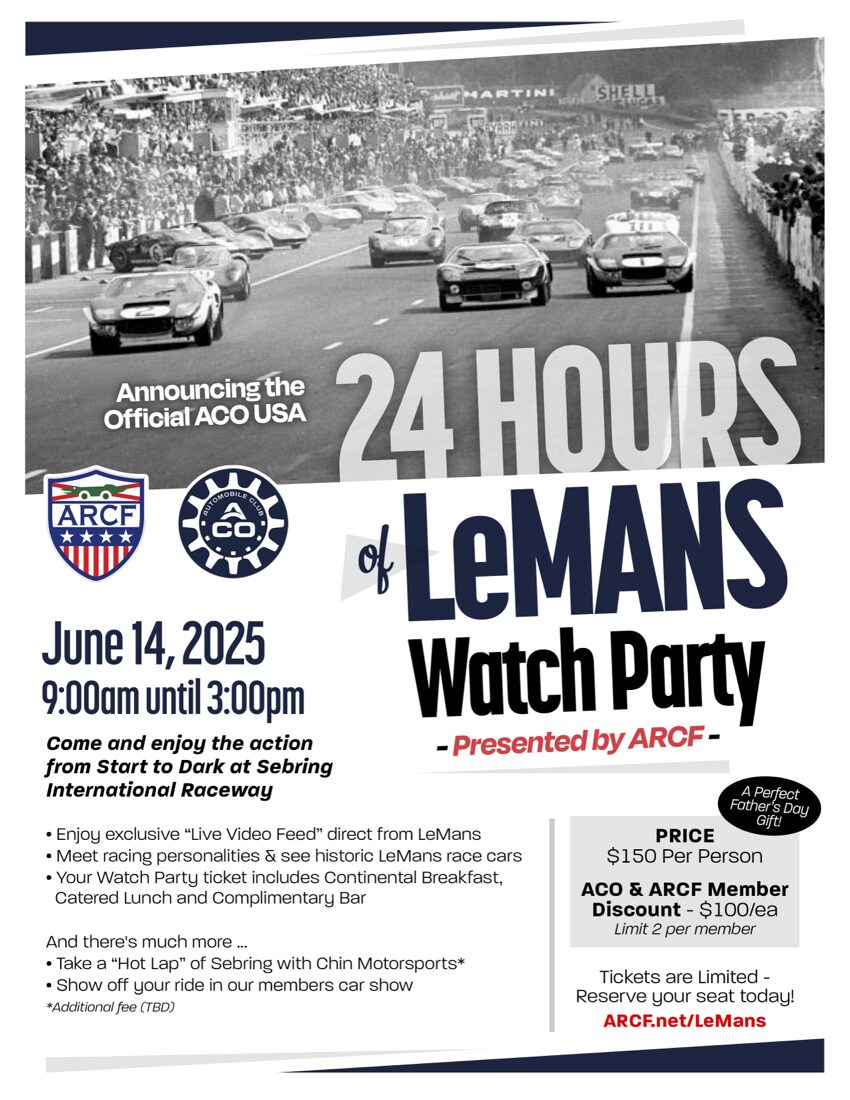

It was not just Sarti and Louise – and by implication the movie going public – who began to question the danger inherent in Formula 1 in the mid to late sixties. Three time Formula 1 champion Jackie Stewart’s revolutionary safety crusade actually began during the filming of Grand Prix, since the beginning of the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix was marred by a huge accident which took half the cars out of the race, and left Stewart himself trapped in the wreckage of his own car, bathed in petrol nursing broken limbs, terrified of a fire breaking out, awaiting rescue for twenty five minutes. The bitter irony here is that Frankenheimer edited Stewart from the Spa coverage, since in real life Stewart wore Stoddard’s tartan band, and Stoddard was supposedly recovering from his near-death Monaco crash at the time of the Belgian event.

While attitudes may not have changed immediately, by the later sixties not even the most gung-ho driver could avoid considering the implications of his profession. “Grand Prix” features wives and girlfriends in the pits acting as laptimers, a common practice right up to the modern age, but one which speaks to the fact that even if the drivers themselves weren’t worried, the people who loved them always were. Through Sarti’s Spa accident, “Grand Prix” also draws attention to the fact that often spectators were maimed or killed even while the driver was not.

Pastiche as it may be, “Grand Prix” ends up paying a wonderful tribute to the real people who participated in what can be seen with hindsight to have truly been the Golden Age of Motorsport. The tribute is valid not just to the mid-nineteen sixties but, but to the whole “epic” period of the sport, from that first wild city to city Paris-Rouen event up to the increasingly commercialized and technologically complex period specifically covered in the film.

I must also confess some considerable personal prejudice about Grand Prix – somewhere in my Heaven, at the foot of an Alpine pass, there is a black ’66 Shelby GT350 Mustang, with the keys in the ignition and the young wastrel Jessica Walter sat in the passenger seat just waiting for me.

Further reading/viewing

- Escaping my list but well worth watching is Frankenheimer’s retro seventies thriller, Ronin. Made in the nineties, Ronin features a couple of cracking car chases, and IMHO, some extremely well chosen cars.

- The Nostalgia Forum is the historic part of the Autosport website. Members have quite the most incredible depth of knowledge on the history of the sport. There is a thread specifically related to Grand Prix: http://forums.autosport.com/index.php?showtopic=26190&hl=grand%20prix

- It is difficult to explain how much better the film looks on a big modern HD screen. Truly, today you can probably get a better viewing experience in your home than movie goers of the sixties – if you know the film but have not watched it in with modern equipment, you should find time to do this asap.

- The original music score is quite, quite dreadful – you have been warned.

*remember Old Man Ferrari wanted to be an Opera star when he was young, and seems to have had a flair both for drama and tragedy.

I really enjoyed your article and appreciate your insight and knowledge of the racing world. However, I think you are much too hard on the film. There are some spectacular scenes in this film, and although melodramatic and dramatic at times, nonetheless, the movie has an overall grace and beauty all its own.

As a racing movie, I can’t think of any better. It has incredible racing footage and unique camera shots that are unparalleled. CGI racing films can’t touch the visceral quality of this film. Frankenheimer has the actual actors driving at high speed for sequences that have a realistic feel that can’t be captured with green screen. There are no under cranked sequences either.

The crashes are done beautifully and effectively. You feel those crashes in your bones.

Thank you for your knowledge and insight into this movie. However, you should reevaluate. Gran Prix in my mind stands tall in a field of languid racing films.

Frankenheimer was seeking a key to make the racing world accessible to a larger audience and chose a path through the relationships romantic and otherwise that they have in this competitive racing world.

Well, everyone makes great points in both statements, but LeMans did a better job of the actual filming of the race scenes. In fact so much so that McQueen ended up being obsessed with that and no real plot to the movie except those filmed sequences which made it so incredible if your a car guy like me. I enjoyed Gran Prix because they did a better job of attempting to tell a story of sort and had relatable characters and emotion was felt in scenes. Either way, both LeMans and Gran Prix are wonderful movies to watch just to get a feel for how truly dangerous and raw Formula 1 was back in the golden era of racing. The side stories too were fascinating between McQueen and Garner as The King of Cool was pissed he didn’t do this movie too because he was an actual fine racer in real life. There were stories of McQueen peeing on Garners flowers in the apartment they both lived in along with other assorted things………