Historiography sounds very ivory tower academics, but really it isn’t. The Oxford English Dictionary defines historiography as “The study of the writing of history and of written histories”.

So, it is about how the story is told: not just who won the race, but whether we watched it live, saw it on TV, or had the story told to us by a drunk man in a pub.

The big point is that critical analysis of news sources is crucial in contemporary society (Fake News). The smaller point is that no one seems to have done this for motor racing history. Just casual reading of a few old racing stories immediately gets you thinking “but that’s not how I heard that story before”, i.e. straight into historiography.

This paper was recently presented at the International Motor Racing Research Center conference at Watkins Glen.

Differentiating Between Richard “The King” Petty and Pixar’s “Mr The King”: Historiography in NASCAR, and Why it Matters

Disney/Pixar’s “Cars” franchise is currently the biggest brand for American boys under ten. Children recognize “Mr The King”, the screen alter ego of Richard “The King” Petty, while the man himself provides the voice. As historians, our ability to interpret and publicize stories of King Richard has been hijacked by Pixar!

This paper surveys the way NASCAR history is currently received and understood by examining existing written sources, the remarkable color film archive which has survived and is freely available on youtube, and physical sources such as cars and tracks. It then makes a case as to the value of historiography applied in a motorsports setting. Fundamentally, we stand a better chance of preserving the history we motor sports enthusiasts love if we are able to improve some of our practices to allow us to stand as recognized academic history.

Hijacked by Pixar? Yes, some Hollywood hyperbola but, thinking more, we can see our sport has always been this way. The event now considered the world’s first race, the Paris-Rouen of 1894, was conceived by a newspaper. The notion of motor sport as international competition was also that of a newspaper man, James Gordon Bennett. Seen from this perspective, Bill France’s vision was to monetize the sport beyond selling papers and cars, to selling tickets for the show itself. Others had failed to monetize a beach race at Daytona; as with most successful entrepreneurs, execution on his vision was what set Bill France apart. The PR theatrics which accompanied the finish of the first Daytona 500, where the decision on the race win was strung out over three days seems sophisticated manipulation of the media for 1959, until one remembers that Bill France was always considering the publicity angle. And look at the photo. It takes less that three seconds to judge who won, not three days.

Motor racing history, particularly NASCAR, is likely to come to people both now and in future first by TV pastiche; for this generation it is Pixar’s Cars, for my generation it was a primetime show such as Dukes of Hazzard, or The Rockford Files, or perhaps a movie like The Last American Hero, a dramatized account of the life of Junior Johnson. In this TV-land context we first see a J- turn, bars in the doors, and learn about bootleggers, stock cars which are anything but stock and good guys outsmarting the misguided law enforcement officers and corrupt politicians. Approached in this way, a ‘ripping yarn’ with Hollywood sheen and sanitization, it is easy to miss that this is Nascar’s truth, and real American history.

When covering a contemporary race it is natural for the production team to raid the archives and find flashbacks of old races which give a flavor and context to events today; that is to say David Pearson is present in the minds of Nascar fans who never saw him race because they have seen many grainy, bleached clips of the #17 or #21 in victory lane while they were waiting for the day’s racing to start.

Today, the ubiquity and quality of information on the internet encourages research: when watching Cars, one wonders “Why were the Hudsons good?” and “Who is that Pixar character based upon?” and can surf and find the answer on your smartphone without moving from the couch.

Many NASCAR races can be found complete on youtube. It is hard to underestimate just how compelling a resource this is. We can judge for ourselves, by watching the actual races, which driver was the most skilled. Documentaries made in the nineties feature interviews with those from the fifties who have since passed, so we have Buck Baker and Cotton Owens in their own words. Moving from the eighties into the seventies, rather than full races, we are more likely to find highlights – perhaps a 500 mile race in twenty minutes – but still very high quality color film with period commentary. As far back as the mid-sixties, we see a similar quality of color film, especially of Daytona. As far back as the fifties, and the film tends to be black and white, and there is much less of it. Tropes of these early films include lurid crash footage with exaggerated skidding noises, tires howling on grass.

Turning to the historians traditional resources – books and journals – these exist in Nascar with a character and a richness which is truly reflective of the sport. Many of the books published in the last two or three decades resemble Formula 1 style Christmas stocking stuffers – the “definitive biography” of the latest champion, despite his being under the age of 25, badly ghost written by a journalist who normally covers a stick and ball sport and delivering an uninformed lack of depth. However, some excellent histories are available, perhaps most notably Greg Fielden’s work documenting each Nascar sanctioned race, and many Nascar figures have self published their work: what we have is the writer in conversation, often a seemingly unedited polemical. Smokey Yunick’s thousand page opus is a well-known example of this, although I have half a dozen self published titles such as Buddy Mewbourne’s memoir. Some Nascar content is available as electronic-only books: the one book I can find on Marshall Teague is available as a kindle ebook only, and admits to being a no more than collected newspaper articles.

Mainstream published Nascar histories are also different from those about other kinds of motor sports. Often the same stories will be repeated in a slightly different form in numerous books. This tends to give the whole thing the quality of a myth. One example is when Curtis Turner landed a plane on the main street of a small town, in order to buy more whiskey. While the fundamentals of the story does not change, some versions of the story have bikini clad ladies getting out of the plane to go in the store, and some have the plane escaping scott free while others have it getting tangled in power lines or traffic lights.

Turning to regional newspapers, with their detailed race reports, my sense is that more even than youtube, these are a vast and a largely untapped source which if studied will reveal surprising insight – my work has been almost exclusively at the book/youtube level.

Disappointingly, most non-video online sources tend to repeat basic information and anecdotes. Some do have fresh material aggregated and these exceptions can offer remarkable insight- eg. littlejoeweatherly.com explaining how he got his distinctive facial scar.

Thinking now about physical sources, the Nascar Hall of Fame in downtown Charlotte North Carolina provides an entertaining visitor experience for a broad range of ages, knowledge and interests. Older and more inaccessible is the Joe Weatherly Museum at Darlington. Static displays are also found in local history museums, such as a Junior Johnson ‘40 Ford in the Wilkes Heritage Museum. Varying in the glitz which they apply to telling the story, all display exhibits which stand testament to Nascars remarkable history, albeit with the paradox that museums are about worthy preservation, while Nascar itself has always been about running wide open and using the car up by the end of the afternoon.

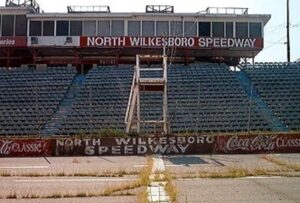

Visiting Nascar’s physical sites offers considerable variety. The rough Jacksonville neighborhood where LeeRoy Yarborough was born, first raced and lived with his mother later in life seems similar in 2017 to how it was 40 years earlier when LeeRoy was alive. His local track, the site of his maiden victory is has all but gone, the modern housing development aping the shape of the circuit. Across the country, Nascar’s first road course, Riverside, is now also a housing estate. The story of the track on the outside of town falling victim to urban sprawl and rising property values is as much a cliche as that of the future Nascar champion sneaking through the fence as a young boy to watch his first race, and vowing then and there this would be his path in life. The decay at North Wilksboro is particularly palpable, and a visit there resulted in my being escorted away from the track, and out of the county, the hostility towards me open.

Daytona Beach is equally astonishing. My visit was in January 2017. The Streamline Hotel, well known as the site of the meeting where Nascar was formed, was closed for a remodel. Bill France’s Gas station has nothing to mark it at such. With Herb Thomas, Marshall Teague was the most successful Hudson racer, and thus forms the basis for the critical, Paul Newman-voiced mentor character “Doc Hudson” in Pixar’s movie. Today, on the site of Teague’s garage is a business which lifts and puts oversize chrome wheels on golf carts. Arguably Nascar’s greatest car builder was Smokey Yunick. His “Best Damn Garage In Town” has completely disappeared, even the foundation has grass grown over it.

Many of the tracks which have survived have changed radically, with tracks like Bristol and Martinsville being first dirt, then paved, and thus utterly different in character.

We must surely accept that the rapid disappearance on physical reference points described here must likely continue; examination across other areas of automobile history show the Cooper Factory near London recently sold for renovation and the first Shelby factory in Venice, Los Angeles an office building, with nothing noting its significance. Indeed Ford’s modernist masterpiece, Highland Park, where the miracle of the moving assembly line was perfected, is now a rather grotty mall in urban Detroit with an atmosphere which rivals North Wilksboro for its hostility.

Racing cars have hard lives, often needing full rebuilds after each event, even if no break down or crash took place. This attrition rate means that “original condition” and “historic racing car” are generally oxymorons. Most are sold to lower budget teams, sometimes competing in a different, lower racing series, and are thus raced into oblivion. More, the interesting engineering innovations which differentiated period European racing cars are often examined and discussed today; that same engineering ingenuity applied in Nascar, with it’s “strictly stock” rulebook, was probably cheating, and by definition something to be hidden, even decades on. So, while there are historic Grand National racing cars, they do not constitute the definitive historical sources we might expect.

The cars may not be original, but nonetheless they remain compelling. What remains is the “I could go out and buy one just like that” element. Joe Weatherly’s ‘63 Pontiac Grand Prix looks like the one l have in my garage, the ones my son and I see at Pontiac meets. The thought of my Pontiac high on the banking at 150mph is pretty attention getting, and the thought of racing guys like Lil Joe, Fireball or Turner terrifying. Even though we know Joe’s Pontiac was built by Bud Moore, and is not just any old Pontiac 55 years from the end of the assembly line, the visual similarity will be an important touch point for future generations asking themselves ‘why drive round in circles ever faster?’

Regardless of the actual authenticity of the cars, as tangible manifestations of the past, striking and impressive in their noise, smell, and dangerousness, the cars which survive are amazing counterpoints to the color footage and stories.

Historiographical method seems to have particular traction in Nascar due firstly to the fact that there are so many contrasting versions of the same remarkable stories. Curtis Turner’s landing a plane on a high street to buy more whiskey, mentioned above, is one example of this. Often the protagonist himself tells the story differently in different sources; when the story is retold by others, another level of obfuscation and embellishment is added!

More than detail clarification, historiography can correct oversight in the accepted cannon: H.A. Branham’s 2015 official Nascar biography of Nascars founder and leader, Bill France contains a remarkable misrepresentation of Carrera Panamericana event. For Branham “Thankfully, there was little material resulting from the France Turner effort” However, the Official Story of the Mexican Road Race publicity book of the event features an amusing two thirds of a page image of France and Turner “hitching” a ride home, in front of a cactus, wearing sombreros. In his 1993 book “Carrera Panamerica, the History of the Mexican Road Race” Daryl Murphy has a great deal “of material resulting from the France Turner effort”. Having shown well early in the going, Bill France had, as Branham points out, ignominiously wrecked their Nash. Well down the field but ever enterprising, they simply bought the sixth placed Nash from Roy Pat Conner, who had fallen ill. On the following day’s stage, while descending a mountain pass, Turner came upon the Italian ace Piero Taruffi in his Alfa Romeo. To pass and win the stage, Turner bumped Taruffi a little, “Nascar style” to ensure he moved aside. Following a flat tire drama, Turner and France still won the stage, only to be disqualified for the buying of Conner’s car. These two impressions seem at odds: for Branham, it was a non-event and illustration of why Bill chose to focus Nascar in the south. For Murphy, it introduced California car builders and racers like Bill Stroppe and Johnny Mantz and Italians like Taruffi and his team mate Felice Bonetto to Bill France, and Nascar itself. Banham has failed to show what Turner and France’s relationship was once – the ultimate leadfoot driver alongside the ultimate creative thinking fixer/manager co-driver. Banham also leaves out the most dramatic image of the whole story, of somewhere high up in a Mexican mountain pass Big Bill and Curtis in someone else’s bathtub Nash ramming Taruffi’s beautiful Alfa until he yielded. To wreck, buy another car, and then ram your way into Victory Lane, a Nascar, not a road racing story, that. The memorableness of stories is important – it’s what makes legend, and Branham missed it. By eliminating fundamental oversight such as this we will go a long way to establishing improved credibility with academic historians.

The other crucial element in making our history accessible for academics is curating, interpreting and presenting stories in a manner which is accessible for readers lacking motoring vocabulary – people who think about a housing development when they hear “small block” and part of someone’s body when they hear “flat head”.

However, historiographical method seems to offer the most interesting rewards around stories which have remained untold: specifically the Pandoras Box of cheating.

Through the university I teach at met a leading car collector. A student, a chemist, was considering setting up a business around confirming the authenticity of collector cars. The car collector’s comment on this was that no-one wanted the service, since no-one stood to gain from it. As a seller, obviously, you want the car to be authentic and original, it’s worth more. As a buyer, you want that too – you just have to be sure of the cars authenticity before making the deal. Even the insurance company want the car to be genuine, otherwise they have less value to insure. So, it is in nobody’s interest to develop improved tests for authenticity, since the only result could be disappointment.

Applying this thought to Nascar, at Daytona in 1962 Fireball Roberts was absolutely untouchable. For Buddy Mewbourne “Fireball was the greatest driver to ever turn a wheel, including Petty, Earnhardt and all the rest. A tiny few argue, to no avail, that Curtis Turner was better.” Writing in his memoirs, Fireball’s car builder and owner, Smokey Yunick, says the car was supercharged. Were this true, no wonder Fireball was so much faster than the others. Moreover, just how great is Fireball as a driver now, if we believe that his super speedway success was simply due to having far more power than everyone else? Certainly, his reputation can only be compromised by research. Given his outstanding performances in the Sportsman series and in a Ferrari GTO sports car, any tarnishing of Fireball’s reputation as a driver might be seen as unfair. Does it matter? To Buddy Mewbourne, I bet it does.

Historiography can help us answer the question, here, however, like the wealthy car collector, I am reluctant to explore this kind of history because it tears down our heroes, while delivering little tangible benefit. Having said this, it is vitally important to consider, because rule bending is so much a part of NASCAR ’s identity: many early racing cars were moonshine haulers, by definition stock appearing cars designed to conceal their speed parts and modifications.

Perhaps what is required is a fresh definition, a word to describe the grey area in the rule book. Speaking at the 1998 Stock Car Legends Reunion “Little” Bud Moore proposes this, since he sees this creativity as part of what defines the sport.

Until we are somehow able remove the stigma from cheating by doing this, we will never learn the secrets – what was done to deliver the winning edge. The more winning the driver, the more they have to lose in terms of status, and hence the less willing they are to share. On the Stock Car Legends Reunion, when asked directly about cheating, Bobby Allison and Junior Johnson both skillfully deflect the question , Junior even raising a laugh (“Nascar caught it all”). David Pearson seems unwilling to own even a fairly innocuous story of his hiding in some bushes on the inside of a turn and leaping out in order to spoil one of Bobby Isaacs’ qualifying laps.

In conclusion, historiography matters because it shows us how, sadly, the notion of “one truth” is a fallacy. Frustratingly, reality is more nuanced – even when Fireball won, the quality of his victory can be tainted decades later by Yunick’s scurrilous and, it has to be said, rather unlikely supercharger claim. (Where would the plumbing go? Who’s reputation grows by this story?)

Historiography matters because it leads us to discover more amazing stories, as opposed to simply retelling the ones we already know – this is an internet trope, and pernicious, because exciting, dramatic American history becomes buried in once-exciting-but-now-dull-with-repetition stories.

Historiography matters because without it mainstream historians will never take us seriously. Having academic recognition matters: when the Road & Track archive needed a home, and was at risk of being discarded as trash, Stanford University library stepped in to save it. This could never have happened without academic recognition of the value of the archive. More, academic historians will help us curate and interpret the history and artifacts we are passionate about.

Big Bill France once said he felt NASCAR was “the best show in racing” and indeed that is precisely what Pixar saw. But between their pastiche, and old men with thick accents telling racing stories there is so much room for american history to be written. Pixar shows us how NASCAR’s place in American history is still open to debate: in our era of “fake news” it never seemed more relevant to look at a modern American institution with the discerning eye of the historian. The Road & Track Archive officially arrives at Stanford