Joe Weatherly was NASCAR Grand National Champion two years in a row, and was leading the Championship when he was killed during a race in early 1964. His image today is shaped by his untimely death: there is color film in the public domain, and it is emotive, shocking, and seems at once senseless and mysterious to contemporary eyes because Joe was not wearing a seatbelt at the time of his accident.

This paper seeks to re-evaluate Weatherly’s career, in the light of his unique achievement: in 1963, he retained his championship driving ten different makes of car, despite often arriving at the track on race day without a car to drive. [NB Upon reflection and further research, it seems likely that Joe phoned round in the run up to races, that is to say when he arrived on race day he likely knew which car he would be driving, but wouldn’t have had a chance to practice or improve it. Once the checkered flag flew, he would be back to asking for a drive ahead of the next event]

Comment will also be made on the compelling sources available.

NASCAR and motorsports in general were exploding in terms of technical developments and performance gains at the time of Weatherly’s career. Featuring cars supposedly showroom stock, similar perhaps to the one sitting on your driveway, yet lapping giant banked superspeedways at speeds above 160mph in a symphonic cacophony of American made V8 roar, it was a sufficiently impressive spectacle for clips of races to get on to the news, and ABC’s Wide World Of Sports, just as color TV became the norm. Car makers were involved, often fielding multiple brands (Chrysler: Dodge, Plymouth; Ford: Ford, Mercury; GM: Chevrolet; Pontiac) and the sport itself was transitioning from its short – ¼ or ½ mile – dirt track roots to paved super speedways more than two miles in circumference. 1964 proved a difficult year for NASCAR. On the heels of the assassination of JFK, Weatherly, the back to back defending Champion and current point leader died in January. A pile up at Indianapolis and the loss of two other NASCAR drivers including super-speedway maestro Fireball Roberts, for Ned Jarrett “the first superstar of our sport” made many, Jarrett included, reconsider the nature of his involvement with the sport.

Joe’s passing was an unusual event in a number of ways. NASCAR is oval racing, yet this event was on a road course, with both left and right turns. NASCAR at the time was almost exclusively based in the south east, yet this event was at Riverside, in California. Weatherly’s Mercury Marauder S-55, built and owned by Bud Moore, ran wide on a fairly slow right hander, and struck the outside retaining wall. Joe was not wearing seatbelt and thus his head came out of the window and struck the wall. Contrary to contemporary sensibilities, Joe not wearing seatbelt is hardly surprising: his biggest fear was fire, specifically being trapped in the car while it was on fire. It must be said that this fear was far from unfounded – since, with bitter irony, that was to be Fireball Roberts’ experience later in the year. At this time and distance, it is hard to add much to the theories about what caused the accident. Engine failure is one possibility. Bud Moore has said that new parts within the brakes failed. The film in the public domain of the incident tends to support this, as the commentator draws attention to the smoke coming from one of Weatherly’s wheels as he enters his final corner. Another version looks at what took place in the race – Moore and his crew changed the gearbox, and Joe was hustling to catch up – and perhaps over-driving the car. Deeper yet, an eyewitness claimed he heard Weatherly struggling with the transmission, unable to get the car into a lower gear to slow it for the corner. The Marauder is a huge car, weighing 4000lbs, and the brakes were drums, so Weatherly would certainly have been relying on engine braking to get properly slowed. Unable to find a gear, it is easy to see how he ran wide at Turn 6, a sharp uphill right at the end of a series of fast swerves. Remembering that the transmission was fitted in a hurry during the race, while the engine and back axle were still at racing temperatures, and it is easy to envisage an improperly fitted gearbox giving Joe the issues the eyewitness described. Due to the film of the incident in the public domain, it is easy to see why contemporary coverage can seem to focus on how Joe died rather than how he lived.

In 1962 Weatherly became champion racing for Bud Moore, using Pontiacs; Fireball had dominated the superspeedway events in Smokey Yunick’s Pontiacs, and as this was clearly the car to have, it was sensible for Joe to remain with Moore. However at the beginning of 1963, political developments – perhaps a Federal Anti-trust case taking shape against General Motors – meant that the factories pulled out of racing – they no longer supplied cars and modified parts to racers such as Bud Moore. Moore told Weatherly he was not going to be able to afford to enter many of the races that season, leaving Joe without a car. It should be said that at this time few drivers competed in all NASCAR point scoring races during the season. Some – in later years, notably David Pearson – would only compete in big money races. Hence it was that although Weatherly was champion in 1963, the story of that year was Fred Lorenzen’s record breaking $100,000+ winnings. Weatherly, like the Pettys, contested all events, including the smaller, lower paying meetings, and, judging from the evidence available, came up with a cunning way to ensure he had cars to drive, and could thus accumulate the points he needed to retain his championship. At that time, NASCAR paid $300 starting money to the current Champion if he started a given event, since having the Champion at the race drew a bigger gate. Kyle Petty says “My grandfather raced for the money” – and indeed so did many other drivers. Looking at the records of winnings through 1963[JS1] , it is clear Joe offered to share his $300 with them if they let him race their car. Indeed, by the end of the season Weatherly had a falling out with Moore, because Moore felt he was driving to finish, to get the points to retain his championship, rather than to win.

Weatherly’s main rival in the championship for 1963 was Richard Petty. Petty built his own cars, with his ex-moonshine running Champion driver father Lee, and his brother Maurice in a small farm workshop overlooked by the bedroom in which he was born. Richard was about to earn the nickname “the King” during a dominant 1964, and he would go on to be the most winning driver in NASCAR history, with 200 wins in a four decade career, almost twice as many as his nearest rival. Let there be no doubt, Joe’s achievement in 1963 is measured against a very high – perhaps the highest – yardstick, since Joe beat “the King” when he was still young and hungry.

Weatherly proved his driving talent in the late forties, as a leading American Motorcyclists Association (AMA) racer. During a five-year professional motorcycle racing career Weatherly won three AMA nationals, including the prestigious Laconia Classic 100-Mile road race in 1948 and 1949[JS2] . It was unusual for a NASCAR driver to transition from bikes, yet it seems clear bikes represented an ideal proving ground for car racing, at least in the middle of the last century, since almost all Grand Prix drivers [JS3] of the interwar period began racing bikes.

Weatherly came to prominence as a car racer in the early-fifties, first as a dominant force in modified racing, and later driving for a team known as the “Purple Hogs”. Weatherly was partnered with Curtis Turner, using Fords, and Turner had the better of the results: in the short-lived NASCAR convertible series, Turner won 38 times against Weatherly’s 12. Often, Weatherly ran second to Turner. The pair were great friends, known for drinking, womanizing and on track showmanship. Another soubriquet they earned at this time was “the Gold Dust Twins”, the gold dust being the rooster tails of earth thrown up into the air by their sliding Fords. Turner was a truly larger than life figure who bought and sold more than half of North Carolina during his time as a timber baron and was, according to veteran NASCAR promoter Humpy Wheeler “the only man I ever knew who threw away the top when he opened a bottle of whiskey”.

Direct comparison between Turner and Weatherly is difficult however, since Turner never raced close to a full schedule, and for much of his prime was banned from NASCAR following an ill-advised attempt to borrow money from Jimmy Hoffa to unionize NASCAR. Certainly, during the era of the Purple Hogs and NASCAR Convertible series, Weatherly seems to have been Robin to Turner’s Batman. Physically, Turner was tall, dark, handsome and fearless far beyond the point of recklessness; Weatherly was short and scar-faced from a teenage on-road car crash, with a penchant for practical jokes, and a peculiar scrambled dialect[JS4] . He wore brown and white loafers which became something of a trademark – indeed, in photographs it is rare to see him wearing any other shoes. Clearly, both understood what today might be called branding, but in period was known as showmanship. Turner and Weatherly called each other “Pops”, the origin of the term being the sound when one car struck another. For Turner and Weatherly that contact might have been on track, to the consternation of the Ford company men, or indeed it might have been rental cars at a stop light or cruising down the freeway.

Rarely is reference made to Weatherly without his nickname “The Clown Prince of Racing” being mentioned. Weatherly’s pranks included riding donkeys in race car parades, fooling the unwary with rubber snakes and stealing the ignition keys from all the cars on the grid right before the “Gentlemen Start Your Engines…” command. Like Glen Roberts’ hated “Fireball” moniker, or “King” Richard Petty, the memorable name is part of the journalist or commentator’s story-telling toolkit, even as it cast Joe as a jester next to Turner’s rugged hero. Joe’s estranged wife might also have struggled with seeing the funny side of Joe’s behavior; she married him despite breaking both her legs in the accident which gave him his distinctive facial scar.

In examining a racing driver’s skills it is important to recognize the only meaningful yardstick is other drivers of that period. It is also important to recognize that statistics only tell part of the story, because greatness lies in how accomplishments were realized, not the volume of race wins/championships. That Joe had outstanding natural talent is certainly clear – he did well on two wheels and four, on loose surfaces and pavement. Anyone racing at these speeds with the safety and medical facilities available in the early sixties was clearly brave to the point of foolhardiness to twenty first century eyes: simply to run with Turner, Weatherly had to be fearless behind the wheel. Fireball and Fred Lorenzen were outstanding on superspeedways, yet Joe won and retained his championship by consistent point scoring on the shorter, dirt tracks. In the fifties, it is clear Joe was overshadowed by Turner, yet by the early sixties, a back to back champion, Weatherly had fully emerged from Turner’s shadow. Rather than a lead-footed joker, he took a pragmatic approach to winning, and should be remembered that way. Away from the track, with his sheer hooliganism Weatherly has perhaps a deeper cultural resonance: to drive a car into a swimming pool is a Hollywood movie cliché, however Joe did it first, racing from a track back to the motel with Turner in a couple of rental cars, for the prize of a bottle of Canadian Club whiskey….

Looking then to sources available to tell Joe Weatherly’s story, NASCAR is particularly rich, since this is recent, geographically localized history is matched with thorough print and TV media coverage, a growing body of literature and a large number of museums, archives and Halls of Fame.

Detailed race by race results and analysis is available, with special attention drawn to Tom Higgins, the sports writer at the Charlotte Observer for over four decades, and Greg Fielden, who has published an encyclopedic four volume history of NASCAR offering a thumbnail of each race, and results including positions and money won. Primary sources – interviews with racing drivers and car builders, both in period and after the fact, and many hours of color film of races from the fifties and sixties is available on YouTube, with more being posted each month. Other online resources, such as forums and the fan page littlejoeweatherly.com proved very useful when learning about Joe, carrying compelling material not found elsewhere.

The traditional canon of motorsports literature – Christmas gift stocking stuffer biographies of the most recent champion written by a sports journalist – has been reinforced by the self-publishing revolution: notable amongst these efforts is Smokey Yunick’s thousand page, highly libelous autobiography/philosophy/racing memoir, “The Best Damn Garage In Town”. Content in both types of literature is often verbatim conversation or polemical rather than a politically correct dull recitation of race results found in many European motor racing biographies, and as such differing and even contradictory accounts of many incidents can be noted.

Although this is recent history, many of the physical sites have changed beyond recognition since Joe’s time. Tracks have been resurfaced, or have disappeared completely: Riverside is now another SoCal shopping mall, David Pearson’s home town of Whitney is now a suburb of Spartanburg, and the original Hollman-Moody base was pulled down to make way for the new runway at Charlotte airport. Standing out amongst the many abandoned tracks, North Wilkesboro is slowly collapsing like a fading Appalachian Colosseum. One place which has not changed is the Petty’s farm, in Level Cross, North Carolina, where even the local fire station is #43, “King” Richard’s racing number.

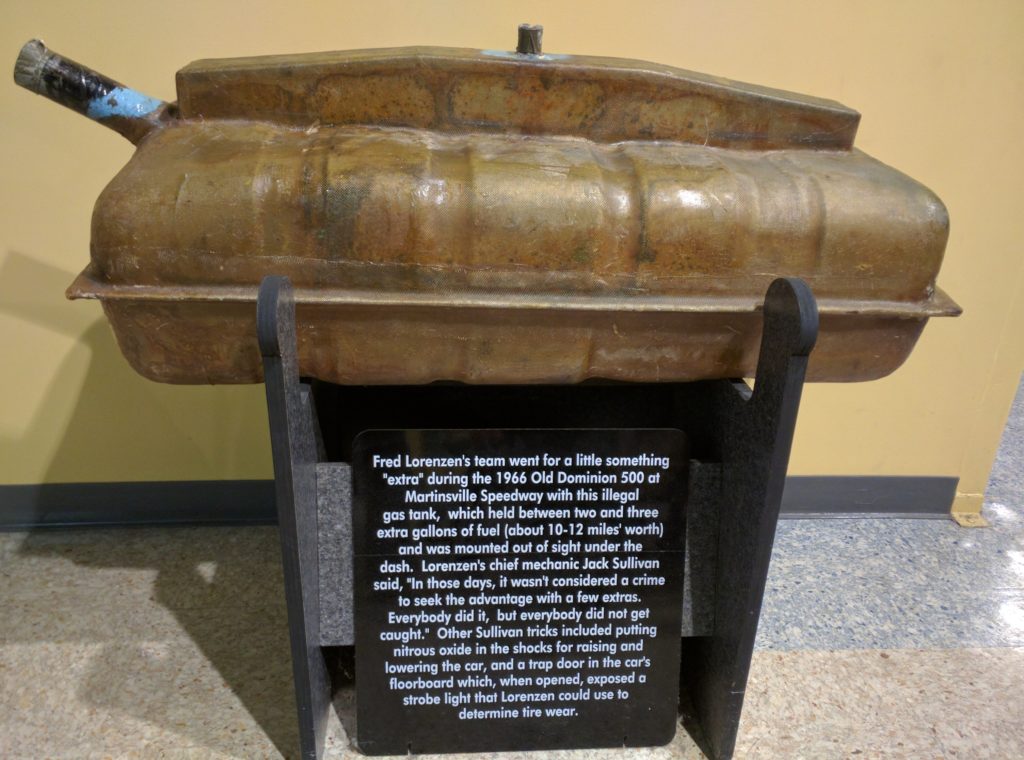

The Joe Weatherly museum offers a cabinet with a picture of Joe, some of his famous shoes and trophies. Alongside is a rare and fascinating exhibit of components constructed with the specific purpose of cheating, i.e. making the cars better than stock. Included is a special Smokey Yunick Pontiac hood, which appears to be steel, but in fact is a clever amalgam of papier mache and aluminum – making it far lighter, and hence the car faster, and an extra gas tank, fitted under the dashboard, thereby giving Lorenzen’s Hollman-Moody Ford an extra two laps of fuel. How much did these things – and other cheats surely missed by NASCAR inspectors – contribute to Fireball and Lorenzen’s success on the superspeedways?

The NASCAR Hall of Fame recalls Joe in a balanced way, the Clown Prince and Purple Hog stories set against Weatherly’s AMA and NASCAR modified Championships and his stock car successes of the early sixties. Inducted a year before Turner in the Class of 2015, Weatherly is one of the first thirty inductees, reflecting his double champion status and that remarkable 1963 season.

Finally, it should be said that the cars which have survived arguably represent the most accurate physical document of early NASCAR and hence Joe Weatherly’s career.

[JS1] Forty Years of Stock Car Racing Vol 2, by Greg Fielden [JS2] Per the AMA Hall of Fame [JS3] For example, Nuvolari, Varzi, Taruffi, Rosemeyer, von Brauchitsch [JS4]“In ’62 ‘Balls won everything but Miss Congeniality in Smokey’s big Indian” Joe Weatherly discussing Fireball Roberts performance at Daytona in 1962. Smokey is Smokey Yunick; Pontiac was a rebellious native american leader, who entered the popular consciousness as the subject of a popular novel just as the GM board were considering how to make-over their Oakland brand: like Hummer a decade ago, GMs leadership felt “Pontiac” properly captured the zeitgeist of the age.This was prepared for the 2016 Drive History Conference, organized by the HVA at the NB Center in Allentown, Pennsylvania. It was also presented at the 2016 International Motor Racing Research Center conference in Watkins Glen, read by Don Capps. It was the first in a series looking at historiography, that is to say HOW the story is told. NASCAR seemed like the natural place to start, because so many of the stories feel like legend: for outsiders, this looks like implausable deeds performed for impenetrable reasons, like the first time we hear Greek Mythology (a dude with a bull for a head? Gods regularly having sex with mortals? A quest for a sheep fleece?) My premise was simple: subjected to the scrutiny of historical judgement, how good a driver was Joe Weatherly? The evening before I was due to present, I met someone who knew Joe his surviving relatives. Presenting to him was intimidating; I wanted to shed light on Joe, but realized that risked tearing down a hero. He sat in the front row, and much to my relief, shook my hand afterwards, thanking me for what I had said.