Part 1: Luke Chennel – John Bond (1912-1989) and his wife Elaine bought the faltering magazine Road & Track in 1949. Over the course of his ownership and editorship, Bond built the magazine into a major cultural force. This presentation examines the dimensions that Bond engaged with his editorial viewpoint from a wholistic cultural lens. Bond built a durable version of car culture, the practices and values of which remain in many forms today, though under challenge from old and new trends in the automotive industry.

Bond’s version of car enthusiasm stemmed directly from two sources: his education at the General Motors Institute and his enthusiasm for European racing. Road & Track’s coverage of the foreign motorsports scene for some time was the only widely available source material for an American audience.

Luke argues that Bond’s two decade editorship (1951-1972) of Road & Track created the foundational dimensions of traditional “car guy” culture, with its familiar and clubby atmosphere familiar to those “in the know,” but also acted in an exclusionary way to women, casual automobile and racing enthusiasts, and those who might have appreciated automobiles from other dimensions than their mechanical design or performance on certain tests.

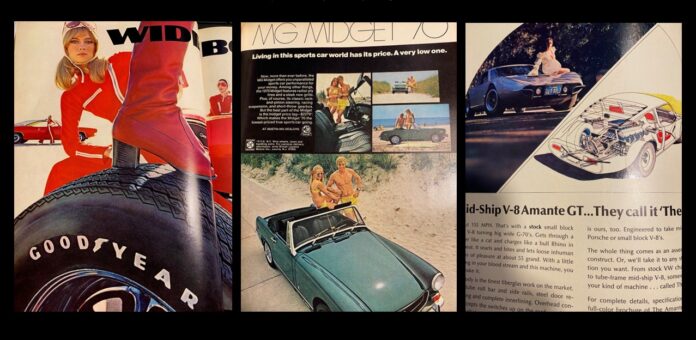

Part 2: Kristie Sojka – will explore the progression of gender representation within the time that John Bond owned and edited Road & Track magazine. It will examine all aspects of the publication between the years of 1951-1972, including cover art, article content, photographs, and advertising. The presentation will compare and contrast the first ten years of Bond’s editorship with the last ten years to identify any potential changes in female representation. With the historical perspective of developing gender politics of the time period, the presentation will consider whether these societal shifts had any impact on women’s representation within the pages of the publication.

Part 3: Ken Yohn – will explore car culture from an anthropological perspective, as a complex whole combining both behavior and the material objects integral to the behavior. This formulation of culture thus includes material artifacts, rituals, customs, language, beliefs, institutions, and techniques, among other elements. This presentation will address two main questions. As presented in Road & Track, what are the essential elements (behavior and artifacts) of car culture? Second, can we learn anything, or draw non-obvious conclusions about car culture by adopting this type of anthropological perspective?

Finally, the presentation examines Bond’s version of car culture in a contemporary light, considering the roles of the changing nature of racing and its relationship to road vehicles, the renaissance in electric vehicles, and debates about mobility in the contemporary climate.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Bio: Ken Yohn

- Bio: Kristie Sojka

- Bio: Luke Chennell

- Notes

- Transcript

- Highlights

- Livestream

- Learn More

Bio: Ken Yohn

Ken Yohn is a social scientist keenly interested in how the automobile shapes our lives. With a Ph.D. in political science and postdoctoral work in history and economics, Yohn has held faculty positions at universities in Japan, Germany, France, and Poland, including a sabbatical as scholar in residence at the University of Science and Technology in Lille, France. For the past 25 years Yohn has been teaching at McPherson College in Kansas, where he is currently chair of the history and politics department.

Bio: Kristie Sojka

Kristie Sojka earned her BA in History from Wichita State University and her MLIS from Kent State University. She has worked in a variety of roles in Kansas libraries for the past 13 years. Sojka is currently entering her third year as the director of library services at Miller Library McPherson College. Her responsibilities include providing library and research services, support, and instruction to the entire campus community. She also oversees the two special collections located within Miller Library: the Brethren and College Archives and the Paul Russell and Company Center for Automotive Research, which houses the special automotive materials collection. Sojka is currently serving as vice president of the College and University Libraries Section of the Kansas Library Association.

The Paul Russell and Company Center for Automotive Research housed within Miller Library at McPherson College currently holds over 5,000 automotive related titles. This presentation will consider the benefits and challenges of curating a special library collection and archives, which supports automotive restoration education. The presenter will discuss the types of materials currently available to researchers, the varying processes of obtaining materials, and options for organizing the collection.

Bio: Luke Chennell

Luke Chennell is an Associate Professor in the department of Automotive Restoration at McPherson College, currently in his 18th year. His teaching emphasis is in mechanical engineering history, focusing on power transmission, steering and suspension, and brakes. His research interests involve early automotive engineering, the cultural history of car collecting, and American railroads in the steam era. His current collector cars include a 1923 Buick and a 1992 Ford Mustang.

Notes

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Brake Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family.

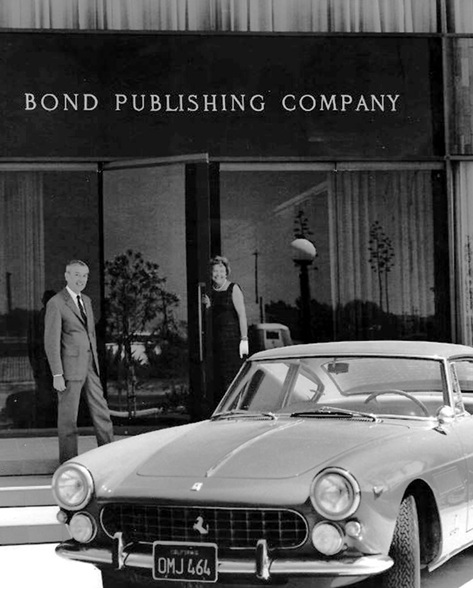

Crew Chief Eric: Perspectives on Motorsport Journalism 1952 1972 with presenters from McPherson College, Luke Chenelle, Ken Yan, and Christy Soja. Forged in print, John Bond, Road and Track, and the formation of the Car Guy culture by Luke Chanel. John Bond, who lived from 1912 to 1989, and his wife Elaine, bought the faltering magazine Road and Track in 1949.

Over the course of his ownership and editorship, Bond built the magazine into a major cultural force. This presentation examines the dimensions that Bond engaged with his editorial viewpoint from a holistic cultural lens. Bond built a durable version of car culture, the practices and values of which remain in many forms today, although under challenge from [00:01:00] old and new trends in the automotive industry.

Bond’s version of car enthusiasm stemmed directly from two sources, his education at the General Motors Institute and his enthusiasm for European racing. Rodentrack’s coverage for the foreign motorsport scene for some time was the only widely available source of material for an American audience. This presentation argues that Bond’s two decade editorship from 1951 to 1972 of Road and Track created the foundational dimensions of traditional car guy culture with its familiar and clubby atmosphere to those in the know, but also acted in an exclusionary way to women, casual automobile and racing enthusiasts, and those who might have appreciated automobiles from other dimensions than their mechanical design or performance on certain tests.

Finally, the presentation examines Bond’s version of car culture in a contemporary light, considering the roles of the changing nature of racing and its relationship to road vehicles, the renaissance in electric vehicles, and debates about mobility in the contemporary climate. Luke Chenelle is an associate professor in the [00:02:00] Department of Automotive Restoration at McPherson College, currently in his 18th year.

His teaching emphasis is in mechanical engineering history, focusing on power transmission, steering and suspension, and brakes. His research interests involve early automotive engineering, the cultural history of car collecting, and American railroads in the steam era. His current collector cars include a 1923 Buick and a 1992 Ford Mustang.

Luke Chennel: Very pleased to be at the Argot Singer Symposium. So I wanted to start off by talking about the genesis of this project, which for me came about almost 25 years ago. A friend of mine and I, growing up, had Mustangs, and driving around our neighborhood, one of the neighbors stopped us one day and said, I have a bunch of old car magazines.

Would you like those? And it turned out he had a lot of old car magazines, and so I and my friend went up with a pickup truck that we borrowed and loaded up an entire pickup truck load of Motor Trend, Road and Track, all of these magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s. The gentleman we got them from had bought a Jaguar XK120 brand new in 1952.

And basically started a subscription to [00:03:00] every publication. So being an avid reader, I found myself reading these magazines for years and years and years and following through. And so I’ve wanted to do this project for a long time because I found those very influential in my own life. And as I reflect on it, I’ve think that these magazines, particularly the work of John Bond has been influential in our broader car culture and want to point that out.

I title my presentation, Forged in Print, John Bond, Road and Track, and the Creation of Car Guy Culture, because, again, I believe that Bond built a durable version of car culture that still influences us today. And it’s my thesis that that culture is now under questioning. Certainly, I think a number of the presentations today have questioned the gender roles, which my colleague, Christy Sojka, will speak to.

But I also see other facets of that car culture under duress or review or under questioning. And so I think it’s important, initially, to establish what that is. The dimensions of car culture are that John Bond forged in Road and Track and think about how our present automotive enthusiasm, racing enthusiasm, and car [00:04:00] culture in general reflects that.

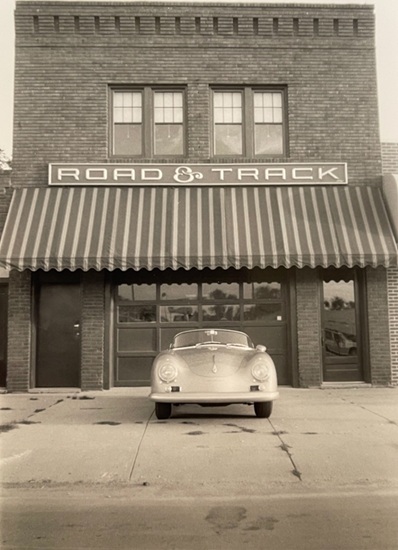

Again, I want to go back to a personal story, and then I promise I’ll stop talking about myself. So, at one point in my life, I found myself in Lincoln, Nebraska, through, shall I say, no particular fault of my own, and Lincoln was a great, uh, Lincoln was a great place, but I needed a job. And so I took a job at the local parts store and I went down to this guy’s shop named road and track.

And I had spotted it immediately. The shop was run by a guy named Bud Dunklao. And so the picture I have up there might be somewhat deceptive in that it might look like an early headquarters of road and track, but it in fact is Bud Dunklao’s shop road and track that he founded in 1962. And so after making my first delivery, Some widget to bud.

I clearly like jumped in and was really interested in his Porsche speedster. He was working on a three Oh eight Ferrari, and we had a very common language. Right. And so bud, who is in his seventies at the time asks me, how did a young guy get to know about all this stuff? And I said, It’s the title on your building, Road and Track.

And so that common language, that common in that we had was [00:05:00] a durable way of intergenerational transfer, which again, my colleague Ken Yan will talk more about in the end of our presentation. First, I think it’s important to establish who John Bond was and really what he thought of his world, how his formative influences shaped him.

Bond was born in 1912. He attended GMI, which is now Kettering University, graduating in 1934 with a degree in mechanical engineering. After his graduation, before World War II, he worked variously for a lot of independent manufacturers. He worked for Studebaker, White Motor Truck, and also Harley Davidson.

And I point that out to say that I believe that working at the independent manufacturers, that Bond gained a real appreciation for them. For the diversity of automotive engineering and also a tremendous appreciation for pre war American cars, which would lead to many of his editorial positions later in road and track in the early 1950s.

It’s unclear to me what role the war played in Bond’s life. I believe he was a member of the service, though I have not been able to research that. What I can tell you, however, is that. Much is in the best years of our lives. He received a dear John [00:06:00] letter during the war, came home to be newly divorced. At which point he met a spouse, Elaine, who also was divorced immediately after the war.

And they set about building a life together. We’re married in 1950. Interestingly enough, their honeymoon. Was driving Bond’s brand new 1950 Ford to Watkins Glen for the road races. They drove from California and I can only say that Elaine must have been a saint to do that for her honeymoon. But Elaine played a key role in the magazine.

She was the one who ultimately, I think, brought about the broader editorial vision and Bond was really just, not just, but he was the executor of Elaine’s broader, grander vision for the magazine. One of the ways to approach people always is the cars they own. And so from an early 1952 issue of Road and Track, I have Bond’s list of cars that he had owned prior to buying the magazine in 1953.

His cars up until then included a 28 Ford, 29 Ford, 30 Ford, 35 Chevrolet, 37 Buick 60, a 40 Chevrolet, a 39 Buick 40, 33 Terraplane 8, 46 Ford 6, [00:07:00] 32 Ford V8, 47 Ford V8, 49 Ford V8, and then finally, probably the most interesting, a 1949 MGTC. And so we see here the genesis of Bond become interested in sports cars through his MG.

Given his pre war experience, he determined that The American manufacturers simply were not competing in this market, and his vision was that there should be the construction of an American sports car. And so Bond begins pushing pretty strongly in the magazine for the development and construction of a proper American sports car.

To do that first, though, he needs to define what a sports car is. And I like to joke quite often that my students often define their pickup trucks as sports cars because they have five speed transmissions, two doors, and four wheels. And that clearly was not Bond’s vision. So in a series of his early editorials, he laid out his vision for what a sports car really meant.

And that vision really was the combination of road and track. It was the idea that a road machine could also be a purpose built racing machine and serve as a driver. Dual function [00:08:00] vehicle for both road and track. And I want to talk more about racing specifically. And so I’ll get to that when one of my future slides, but one of the other major dimensions of car culture that Bond brought to road and track and ultimately to, I think our broader one is the determination that to be a true car enthusiast, you needed to have a deep historical background, which certainly the people in this room and myself consider a very important.

characteristic. But in particular, he used history as filler content. And I would use the December 1952 issue as particular evidence. When there were no racing events to cover, the issue was entirely automotive history and pre war automotive history. Bond regularly used historical examples to back up his logic and reasoning for how there once had been an American sports car industry and should be again, particularly manufacturers like Mercer, Duesenberg, and others.

And so Bond could never quite figure out exactly where this fit in the magazine until really about 1955, 56, 57 when it was codified into a standing feature in the magazine, the Salon, in [00:09:00] which classic cars, particularly classic European cars, were dissected not only from a mechanical standpoint, but from also a design standpoint.

And so it’s always been a great question of mine, why in America we have so many French concours style events. And I would point to John Bond salons in road and track and their enduring influence in creating an American appreciation for French cars in particular, in French design. The other piece that I would like to point out as a dimension of Bond’s kind of automotive enthusiasm was that he loved weird cars.

The more strange and kind of outlandish he could think of, the more he found interest in publishing those cars in the magazines. He was interested in oddities and variations. And I think kind of the pinnacle of this was when Robert Cumberford published a series of questions in 1957 suggesting a new ethos of design for automobiles, a simplistic design.

design, and a gentleman named Stan Mott developed this car he called the Cyclops, which was the ultimate minimalist form of the automobile. So the Cyclops became a regular feature in the [00:10:00] magazine, said to be the most raced and mythical car in the world. I would also point to this as an example of Bond creating his own world.

He is a myth maker. He is someone who sees. Not only the opportunity to report on the world as it exists, but also the opportunity to influence and to build his own vision or the visions of others into reality. I want to particularly dive in, finally, to the role of racing and what role racing has in the development of cars.

Bond and Lane were both avid attendees of various races. I have a photograph of them here on a DKW van, really oddball car, but attending and timing road race in the 1950s. Bond watched, I would say, very intently the developments of the American manufacturers and European manufacturers. His long running column, Miscellaneous Ramblings, was aptly titled, in that it was mainly a series of reports on engineering developments, not only in American cars, but also in European cars.

I’ve referenced that photograph from Veloce today, which has a really excellent primary source interview with John Bond Jr. on the history of [00:11:00] his father, and so I’ll give you some reference material there. He lays out, really, in 1952, 1953, the idea of building a true American sports car, declares that American manufacturers simply have not done it and are not going to do it.

He views the introduction of the Corvette with quite a bit of skepticism. He writes, rumors of a new sports car from a large established manufacturer in this country seem authentic. Is it too much 50 50 curb weight distribution, fore and aft, brakes that won’t fade, a straightforward manual four speed transmission, and steering that requires no more than three turns of the wheel, lock to lock?

The Corvette, at least in 1953, had none of those things. So Bond was again very skeptical of that. So he takes his own path and then builds a series of articles on American sports car design and does essentially a rehash of American engines, chassis, all sorts of combinations that he thought would make the proper American sports car.

So throughout the 1950s you see These broad features on independent backyard manufacturers attempting to build the great American sports car bond [00:12:00] pushes and pushes and pushes and competition is his real watchword. It’s his belief that competition is the one arbiter of performance and that if a car is not competitive on the track, that means it’s a failure.

And so I would jump forward to 1964 when Ford announces their total performance campaign. And so here’s what Bond writes in road and track. He says, April 1964, 10, 12 years ago, road and track was a lonely voice crying out that U. S. manufacturers should support motor racing in some form or another. Now, in the shape of FOMOCO, we have it.

And not just in token form. In summary, the Lola Ford GT, and we say it’s about time someone in the U. S. decided to take racing seriously. Ferrari has done a marvelous job of building up a well deserved performance image, but they can be beaten. And it’s about time someone did. Not even in the days of Mercer, Stutz, Duesenberg, et cetera, have we seen such a concerted effort towards all out racing from one manufacturer in all facets of the sport.

Meanwhile, the rest of the industry sleeps on. So, Bond maintained a very critical voice toward the American car industry, again, because [00:13:00] he found them lacking in performance. I would emphasize here that Bond’s role and vision of The role of racing in the development of road cars is paramount, and certainly think that emphasis on performance is something that is a durable and again, transient version of car culture in our present world.

Bond, after Ford wins Le Mans, which he considers the pinnacle of racing, after Ford wins Le Mans in 1966, Bond really, in some sense, loses his direction for the magazine because he’s, in some sense, achieved his goal. So while he’s still interested in pursuing engineering notes and miscellaneous ramblings, there’s a real transition period when the magazine starts to grow and Bond effectively cashes in to the point where he sells the magazine to CBS in 1972, more or less goes back to California, builds his own garage, a stable of roughly 15 cars, and essentially is retired until his death in the early 1990s.

However, I would like to point out that Bond did build, in fact, a durable movement, and particularly a number of [00:14:00] followers of his movement to the point that when safety regulations became a major contention in the early 1970s, it was the readers of Road and Track that mobilized to write letters to NHTSA, the EPA, and others to try to push off, stave off, safety regulations, which they viewed as interfering with The ultimate goal of performance and design of their cars.

So from 1972, I have this. Remember that proposal of the NHTSA to limit the top speed of new cars to 95 miles an hour and require flashing lights and a honking horn at anything over 80 and our editors, March, 1971, calling readers to action in opposing it. Our readers and other motoring enthusiasts responded.

NHTSA held its docket on the proposal until long after the original closing date because of the flood of mail it got. And when the docket was finally closed, they had 24, 300 responses. Eight times as many as they’d ever seen on a proposal. And so, Bond creates an army of movement enthusiasts who want to build and grow the vision that Bond saw in the pages of Road and Track.

So, it’s [00:15:00] not just about Bond as a poll influence on the media, right, where he reports on what he sees. He’s also able to create a push factor. And so, at this point, I would like to turn over to my colleague, Christy Sojka, who will discuss the role of gender and the creation of car guy culture in particular through the pages of Road and Track.

Thank you.

Crew Chief Eric: Woman’s Place in Car Culture. John Bond, Road and Track, and the Evolution of Gender Representation by Christy Soja. This presentation will explore the progression of gender representation within the time that John Bond owned and edited Road and Track magazine. It will examine all aspects of the publication between the years 1951 and 1972.

Including cover art, article content, photographs, and advertising. The presentation will compare and contrast the first 10 years of Bond’s editorship with the last 10 years to identify any potential changes in female representation. With a historical perspective of developing gender politics of the time period, the presentation will consider whether these societal shifts had any impact on [00:16:00] women’s representation within the pages of the publication.

Christy Soja earned her BA in history from Wichita State University. With an emphasis on women’s history and her MLIS from Kent State University, she has worked in a variety of roles in Kansas libraries for the past 14 years. Christy is currently entering her fourth year as the Director of Library Services at Miller Library at McPherson College.

Her responsibilities include providing library and research services, support, and instruction to the entire campus community. She also oversees two special collections located within the Miller Library, the Brethren and College Archives, and the Paul Russell and Company Center for Automotive Research, which houses the Special Automotive Materials Collection.

Her favorite aspect of working in academic libraries is the connections she makes with students. She also enjoys the relationships she has built since coming to Macpherson College with automotive enthusiasts from across the country.

Kristie Sojka: I am thrilled to be back here for my second year at the symposium and so grateful to Luke and Ken for [00:17:00] valuing my perspective that I bring to this topic.

Unlike Luke, I have not been familiar with Road and Track for 25 years. As a librarian, my familiarity with Road and Track was pretty much based on they come in, I catalog them, and they go on the shelf. And so I had to spend the last several months really immersing myself in this 20 years of the magazine.

And that involved just sitting down and going cover to cover. And I I read many pages of content. I looked at lots of advertising and you’re going to see that. And I will say that I really had to just do that deep dive and really look at what was happening while also thinking about what was happening in society at the time.

Luke gave us a great history of John and Elaine Bond. [00:18:00] One of the things that kept coming to my mind As I looked through these years that they were owners of Road and Track, was a piece of advice that I received from my mother in law as I was about to marry my husband, and she said take interest in each other’s interests.

And I feel that John and Elaine were really partners in this enterprise and I was very optimistic about what that might mean for this publication and what it would mean as far as women being represented in these pages. I have looked through the magazine, as I said, cover to cover, and so I thought I would start with cover art.

And we have these two examples where we do have some ladies who were represented on these two different covers. Very interesting. Both of these are from 1953, just a few months apart. [00:19:00] And the one on the left, this is a model. And we do get her name in the cover information. The cover on the right, these are two young ladies.

It really says in the cover information, these two young ladies work in the office of the Healy Company. And we don’t get their names. I thought that was a little telling. The other interesting thing about the cover art, these are the only two in the 20 year run that I looked at that actually had women on the cover.

So, I appreciate that they’re not draped over the hood. I do appreciate that, but I will say, Along with that, men are not really featured on the cover of Road and Track during this time either. It’s really about the car, something that sort of became a theme for me. So, article content. This caught my attention early as I was looking in the early 50s issues.

There was a series of four letters to the [00:20:00] editor and these were titled, A Yank Abroad. This was an American gentleman who was traveling around Europe by car, attending European races. In that first letter, he makes a reference to we at some point. We did this, and I thought, well, who is the other person in the we?

When we get to the second letter, we find out that the other person is his wife. He actually references her there, but she doesn’t have a name yet. We don’t get to learn her name. He’s writing in that second letter about his navigator sent him off in the wrong direction and, and then we find out that his navigator is his wife.

When we get to the third letter, we get this lovely editor’s note at the top explaining what this series of letters is about, and they tell us Mr. Harrison, who with his wife, is traveling around Europe. So again, we know it’s his wife, but she doesn’t have a name. [00:21:00] Finally, in the fourth letter, we get to part four where it says Burton and Helen Harrison.

She finally has a name, and it’s wonderful, and so I thought this was a really interesting progression. And then, as I studied more article content, I came across this really interesting little blurb titled Madame Unique. This woman in the picture on the left is a Czechoslovakian woman who was a race car driver in 1927 to 28.

She actually quit racing after her husband, her first husband, died in a racing accident. And so that prompted her to stop racing, but they It caught up with her where she had the opportunity to take a spin in a race car again, and she was expressing how much she enjoyed that. So I did appreciate this nod to her.

This next article was a gentleman who was pondering the possibility of sending a postcard [00:22:00] to other annoying drivers out there on the road, sort of like a very polite version of road rage. And we see at the top, Dear Madam, so this This postcard goes out to a woman that he encountered on the road, and he says, What irritated me was not the stench of potion coming out of your exhaust.

And so, obviously, we’re likening her to a witch at this point. With driving tactics like these, how have you managed to grow so old and ugly in the first place? And then we hear, For your own safety and mine, let me suggest that you trade in your broomstick on a wheelchair, but be sure and let somebody else push it.

Interestingly enough, that was about mid 60s when I found that article. Early 70s! I start seeing a regular column by a female writer by the name of Elizabeth [00:23:00] Hayward. And so I thought, okay, finally, we’re getting some great positive female representation. And that continued. I had this, you know, this optimism that built up.

When I got to this story about the Sun Valley Portia Parade, I believe this was a 19th century 70, maybe 71, but they gathered in Sun Valley. There was a concour where men and women could all enter their cars, and they were judged equally and not divided into two classes. However, there were two races that took place, and when it came time for the races, there were two different classes, one for men and one for women.

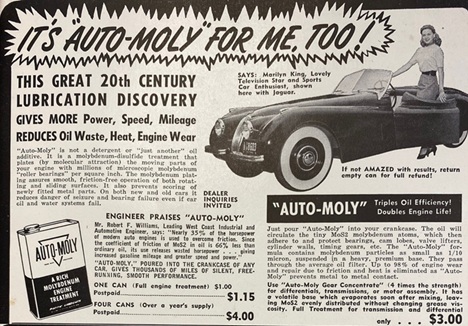

But the really exciting thing for me was that we have these female boosters listed the first, second, and third place winners of each race. And we have their names. By 1970, we’re getting to the point where women have names. And I love that. So we’re going to switch gears and we’re going to talk about advertising a little [00:24:00] bit.

Actually a lot. This is where you really get a real sense of female representation. So on the left, these first couple of ads, these are actresses that they posed next to these car companies. And so we just have sort of this elegant movie star aesthetic. Over on the right, we have ads for a women’s.

product. So we’ve got some head scarves here. So if you’d like to purchase those for your significant other who might be writing with a top down next to you, you have that option. In the 1960s, I start seeing these lovely ads by a company called M. G. Mitten. They are two page spreads. And at the top of the first page, there is this little note called Marion’s Meanderings.

And every month, it’s a different note to potential customers. I was just intrigued by these little [00:25:00] notes from Marion, and so I wanted to know more about Marion. And so I went out and did a little side research and found out that Marion Weber was the owner of MG Mitten. This was a company that she founded.

Her husband had an MG and she sewed a cover for that MG. When he would go to his meetings of the MG club, all of his friends and club members were like, we need one of those too. And so, This light bulb went off for Marion and she started sewing more of these car covers. It evolved to the point where there were other items for sale, gloves, scarves, jackets, all sorts of driving apparel.

And then the M. G. Mitten, obviously, a literative term for that M. G. car cover. And then so she took that and said, well, how about a Porsche Parka? or a Ferrari frock. I just really enjoyed doing that little bit of side research about Marian Webber. [00:26:00] In the late 60s, she moves away from this Marian’s meanderings and she hires Dave Deal, who is a cartoonist, and every month he has a different cartoon to go along with her little note instead of that picture of her.

So, a really, really interesting lady. So this is an evolution of carpet ads for your car. This is the same company, and we go from left to right here. We’re on the left hand side, early 60s, and then that middle ad is from about the mid 60s, and then we get to the late 60s. You’ll notice that the clothing has left as we have progressed forward, and I’m not sure about any of you, but I don’t know anyone, male or female, who hangs out like this on their car carpet.

No pun intended there. I will also point out, because I think it’s so fascinating, [00:27:00] because as a librarian, I’m focusing on this new world of artificial intelligence and AI images. If you look at that last picture over there, on the right hand side of the screen, you’ll notice something about this woman.

She has three legs. You might not have noticed that before. So then we continue. Goodyear has a variety of ads. They were really prolific within these pages and a lot of them featured women. I really liked this one. I sort of was thinking about boots and that we hear boot as kind of a nickname for tires, right?

And so I thought that was interesting and I had, you know, that Nancy Sinatra song running through my head as I look at this ad. In the middle, we have this midget ad and I think of this. as The Beach Barbie and Ken. If you get this midget, you can have this golden lifestyle. You can go to the beach and be tan.

And we have this midship ad [00:28:00] where we do get a woman draped on the hood of a car. Continuing with advertising in the 60s, I loved this ad for WD 40. The color just sort of appealed to me. But I also thought This could also be a great ad for hairspray. In the middle, this is an ad for a solicitation to join a group against government regulations on sports cars and racing.

And we can see Lady Liberty portrayed in a not very attractive light here. And VW parts ad. Again, I don’t know anyone who’s standing around with their parts like this. But, you know. So these two ads I thought was interesting for myself personally. These were the two that sort of raised my feminist hackles the most.

The one on the left is a Honda ad titled, Men’s Liberation. This was in the 70s. So [00:29:00] we have this, you know, resurgence. of the women’s liberation movement. We have the equal rights amendment. All of this is building up once again. And I just, I get it. I read through the content of the ad. I understand what they’re saying.

You know, it’s stressful getting away on your Honda is awesome, but I don’t know. I thought it was interesting, that play on the women’s liberation movement. And then the BMW ad, take me to your husband. This one really hit me personally because I’m the one who drives the BMW and not my husband. But I did take a step back, remind myself.

This was 71 or 72. Women in the United States, at this point, still cannot buy a car without her husband cosigning for her, like getting a car loan. So, you know, maybe in that sense, it sort of makes sense that you would take this car to your husband. It does say at the end, if you read [00:30:00] through the content, at least it’s not another woman.

Okay, so now let’s shift over to some photographs from some of the contents of the articles. This first one on the left, I really tried to find photographs of women attending races. It was challenging because, as you know, the crowd is often really blurred in those types of photographs. But I did find this one where I have a couple of women who are at the race.

And then these next two are really interesting. These two ladies are in the pits. They’re in Daytona. And obviously, relevant enough to have two pictures of them in this story. But again, they have no name. Neither of them has a name. And we don’t really know what they’re doing. In the middle picture, the woman on the right hand side, I believe she’s got a clipboard.

And stopwatches and things like that. So I’m wondering if they’re the significant other of one of the race car drivers, but I’m not sure because there’s nothing about them within the article or the captions. Auto [00:31:00] shows. Here we are, we’ve got the models. This is where the women are really leaning against the side, draped over.

This was the 1970 Paris auto show. I don’t know how well you can tell, but she does not have anything on. Those guys are not looking at the car. And I’ve got a few cartoons that I came across where we’ve got some women. This first one says, the brakes were fading badly in the eighth lab. And then in the ninth, I broke a bra strap.

And then in the middle, we have this gentleman, I assume an engineer, and he’s drawing out these curves on this chart while thinking of other curves. On the right hand side, we have some wishful thinking happening here with this gentleman, maybe not very enthused about getting in the car, you know, with, I assume, his wife, and really thinking about this young lady who’s over buying this sports car.

As I said, I was really optimistic because of Elaine’s [00:32:00] involvement with the magazine that I would see more female representation within these pages, and I’m sort of let down. I feel a little disappointed. On the other hand, I think that John Bond’s focus was really on the car. There are the sections on the races.

They do talk to the male drivers, but we heard some great things from both Lynn and Chris about female race car drivers that were racing during this time, and I didn’t find any. Anything about them in these pages. So there’s just that sense of disappointment for me, but I thought I’d leave with this page.

This is a dedication in the book, 50 years of road and track, and it says dedicated to John and Elaine, to whom we owe it all. Now, I will transition to my colleague, Ken Yong, and he’ll wrap this up.[00:33:00]

Crew Chief Eric: An Anthropological Perspective, John Bond, Road and Track, and the Formalization and Transmission of Car Culture, by Ken Yong. This presentation will explore car culture from an anthropological perspective as a complex whole combining both behavior and the material objects integral to the behavior. This formation of culture includes material, artifacts, rituals, customs, language, beliefs, institutions, and techniques, among other elements.

This presentation will address two main questions, as presented in Road and Track. What are the essential elements, behavior, and artifacts of car culture? Second, can we learn anything or draw non obvious conclusions about car culture by adopting this type of anthropological perspective? Ken Yan is a professor of history and politics and department chair at McPherson College.

In his 26th year at McPherson, Dr. Yan’s teaching responsibilities include courses on social and cultural history of the automobile, technology and social change, and international travel study courses focusing on European automobiles. His doctoral work in political science [00:34:00] was followed by post doctoral work in history, economics, and intercultural communications.

His personal interests include the restoration of vintage European racing bicycles and long distance cycle touring.

Ken Yohn: Very good, thank you so much. A continuation of road and track and car culture, and this time I’m looking through a lens, and it’s a photographer’s lens, and look at the intergenerational nature of car culture, which we’re all profoundly interested in, exactly where is this headed, 20, 30, 40, 50 years from now.

40, 50, 100 years from now. But first I want to zoom out before I zoom in, and I want to talk about the way this kind of project evolved from last year’s meeting here, tied with other experiences that the three of us have had in academic experiences, and one of them was the recurring nature of the concept of car culture.

It’s appearing again, and again, and again. And three quarters of the presentations have made reference to culture. And so one of the things we thought, well, is there anything we can do to contribute to that discussion? Luke and I, about 15 years ago, began teaching a series of courses at the University of Science and [00:35:00] Technology in France and Leipzig University on the cultural structure of technology.

And so we thought maybe we could take some of those ideas and roll them over into this. And so here’s kind of what we have is one thing we can notice is that there’s a whole raft of different ways that car culture is used in different contexts. One thing you might say within a country that there’s a car culture subset of the natural population is relationship with the cars is a key part of their identity.

And we break that out into all different kinds of flavors of that in different venues and different fans where we have dirt track or F1 or rat rod. Thinking of Katherine Wirth in Australia talking about an upper class racers as well as gentleman racers with Jim Miller about Mark Howell’s NASCAR nature and so we were using these terms pretty regularly here.

One of the first things that really enamored me with this conference was the kind of loving reminiscence I heard from some of you. speakers about their experiences at Watkins Glen, and particularly that even this venue had a specific culture, if you will, whatever that might mean. We [00:36:00] talk about national car cultures, U.

S., Germany, Italy. It’s a critical influence in national life. And then there’s, you know, a question that emerges again, is the German car fundamentally different from the Italian car? Is that fundamentally different from the Japanese car? And what is the reason for that? Is there some underlying spirit that’s behind it?

We have a range of practices. We refer to fast foods, drive ins, movies, cruisings, clothing, film, music are all elements of car culture. And then we have this global way of life that we embrace as the pinnacle tool of mobility and power and economic engines within our society. And then finally, the kickback.

And we often think of the kickback and the opposition to car culture as maybe outside of car culture, but it’s actually a fundamental part. You know, the questions and challenges about The deaths on our motorways or what’s happening to urban congestion and design and disenfranchisement of property for minority groups from where the highways were chosen to be built and the critique of the cars are fundamental.

So we, for a breakdown, it’s actually opening it up [00:37:00] rather than closing it down. And I want to clarify that a lot of times what we do when we define cultures, we build the definition of anything, is we’re attempting to create the space and say here’s where our discussion is going to be bounded. And actually, this definition that we’re kind of building and discussing today is one that does the opposite.

In fact, it’s an attempt to unbound it. To say that there’s no definitive authority that gets to say where culture is drawn and where it’s not drawn. And part of this was, you know, an inspiration. I was listening to Don. It was every time when he wraps things up, he talks about future research agendas and trying to put the pieces together to understand how our different efforts combined to a broader understanding of this thing that we, we all love.

And, and one of the things I did in my project was catalog the use of children in photography. Watkins Glen is the only racing venue in the United States that road and track ever showed pictures of children at. You all noticed that Watkins Glen was treated differently. So this venue has a special car culture, but how do we capture that within definition?

So I started by digging with [00:38:00] the most general definition and obsolete definition I could have so that we were going to kind of undefine what culture means. Not define it, but undefine it. Something we can talk about is a complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, customs, capabilities acquired by man as a member of society.

And of course, I chose this specifically because this is One of the things that’s under fire, that we know that that doesn’t work anymore. But there’s other things we really love about this, and that’s we’re talking about capabilities. Because when we’re talking about capabilities, we’re talking about agency.

We’re talking about car culture is something that’s actually created. It’s not just a static domain that you live in. And if you look at, All of the presentations, one of the fundamental logical levers we’re all using is change. It’s a change in events. What prompted a new way of designing an Alfa Romeo?

What prompted another way of expressing national identity? What prompted another reason for creating a car series for women drivers? And so that’s our delta, if you will, like we’re constructing experiments. They’re [00:39:00] experiments that nature creates for us to test our ideas. And so this idea of capabilities and the acquisition It also becomes an important part of the way we approach it because one of our central questions is how is it acquired?

And that’s why we turned to John Bond, because he’s an agent of transmission of culture and why we’re looking at media as a way to understand it. And then it happens within an exogenous, we have an endogenous sense of agency from capability and then you have an exogenous structure of society. The things that change around us in development, whether it’s environment or technology.

And then it gives us a research agenda. You know, we’re talking about the language. We’re talking about the automobile as an object of art. We’re talking about the set of tools the vehicles themselves. We’re talking about the codes, the laws, both formal and informal, the institutions. One of the things I sometimes ask my students to do is pick any event in their lives and tell me the automobile story, you know.

In a wedding, what is the automobile rituals of a wedding? Tying the cans. Photo of the best man holding the keys out. Say, you got to get out of here. Here’s the [00:40:00] keys. You know, and we have all these things that you get a special car. But at any rate, it permeates all the things we do. And so then you have, again, to reopen it up and say it goes on and on and on.

So these were kind of a kicking off point for how we wanted to do it. And I especially like this idea of the complexity of it. And so then, now I want to take another level and say that this acquisition, When we were starting to teach the technological structure of culture, we realized that it became an endless pit.

And much of the things that we talk about in culture, we can point to these things really easily. You know, the food, the dress, the music, the visual arts. The thing about culture, the reason it’s a touchstone for all of us as a discussion, is because we know it’s actually very intimate, and it really shapes deeply the way we think.

And so interculturalists, they’re not anthropologists, they’re not sociologists, but they’re a branch of social science that really begins this wide open definition of culture based on the identities that you choose, which is [00:41:00] actually more in line with the way we think about culture. We think about, you claim your culture, I don’t sign it to you.

It represents courtesy, you know, like the courtesy of who opens a car door for whom. Our behaviors, nonverbal communication, how close do you stand, where do you stand near each other, and how do you, the notions of modesty. And it gets deeper and deeper about understandings of physical pain, what we consider to be kinship and family.

And so all of these really deep structures of how we interact with the world are actually embedded in car culture, but it’s really difficult to see from the inside. And you never think of it as something that needs to be explained, it’s just how you are. And so this intercultural perspective of when you have different cultural dispositions encountering each other and exploring that encounter, it makes a really good theoretical lever for building understanding.

This is a sample of one of these models that’s used by interculturalists. I didn’t want to teach you the model, but this is a sample. For example, Geerd Hofstede has the dimensions of national [00:42:00] cultural life, and he’ll say, for example, there’s a power distance of the hierarchical spaces we have. I taught in Japan for three years, and I can tell you when I walked into a Japanese classroom, it was like, you know, the admiral walking onto the bridge of an aircraft carrier.

And it was dramatically different. That power distance, which varies, this idea of uncertainty and avoidance, what kind of risk you take, this is an automotive class. This is at the heart of automotive racing. What does it mean to take those risks? And why do we admire the people that do and understand the technicals?

This idea of individual versus collectivism, which we’ve been talking about again and again, is part of self autonomy and self reliance and how it emerges in different parts of American culture. Masculinity and femininity is the core of this. Different cultures do it in different ways, express it in different ways.

Long term outlook. Are you looking for 20 years, or 30 years, or 40 years down the line? Are you solving it? But anyway, this is one of the ways you can do it. And so you can readily see how you might take a framework like this, and were you to go down this path, you would find that there are actually mechanisms for measuring these things.

And you can rate and compare. If you ever [00:43:00] Google Geert Hofstede, you can look up how these things work in Japan versus how they work in Germany versus how they work in England. And there’s a really great paper to be written there to compare drivers using these kind of analytic frameworks. But when I burrow down to get to my topic, What I wanted to add was this intergenerational dimension.

I wanted to get to this idea of how we acquire and how we distribute car culture. Because everybody wants to know what’s going to happen and we have these different ideas of how diffusion, that this approach to culture is really useful because it talks about how it changes and how you maintain it and how you preserve it.

Expansion diffusion is just the idea that it’s always moving from one place to another from a strong liberal source, you know, like social class. Within social classes, they develop standards for inter ownership patterns and racing patterns. Gender is diffused expansively. Contagious means from person to person within social equals.

So for example, if you have an audience at a race and you’re all bumping shoulders and you’re cheering and [00:44:00] you’re chatting and here. This is a diffusion among social equals, where you gather to spread ideas with each other. It also happens through government and authoritative sources. And this is not as significant a role.

But I want to get down to this one, this idea of relocation. So, like, Blackton Glen is such a great case study for this. because it represents both this expansion among fans, but it also recognizes that it’s a relocation of this traveling nexus of racers and vehicles who go from place to place to place, and it spreads out.

So if you look at car culture in Watkins Glen and the surrounding area, you have like a pebble being dropped into a pond in a series of ripples that travels across societies and across space. And then finally, this question of intergenerational, how does it move from one culture, and I was thinking specifically, Chris, when I was hearing you talk about the F1 Academy, I was thinking, you know, this is someone who is intentionally trying to diffuse it across generations, and when Luke was talking about him as a kid picking this up, John Bond, really not [00:45:00] interested in transferring across generations.

That’s not his goal. And so it’s just something that doesn’t appear. We’re going to talk about Signal, the messages people use to transfer questions. And so, this thing, we chose road and track images, and it became apparent to all of us as we began doing this research, that we found two road and track magazines.

We found one road and track magazine, It was generated by the publisher images and we found a second Road and Track magazine that was generated by the advertisers. And at first we thought, well, you know, this is a disconnect and maybe the advertising, but maybe the advertisers actually understood Road and Track more than the publishers did.

Because you publish it, you have your scarce resources, you’re applying them to the magazine, but the advertisers who have a lot of money on the line are trying to assess exactly what is the real market here, where is this really going to, and so it’s two different interpretations. And so if we look at these images.

It becomes broken down into a couple categories. We have non intergenerational content, which is the vast [00:46:00] majority. And it’s super technical. The sports car design number nine, frame analysis in one easy lesson. That is not one easy lesson. It’s all math, and it’s all fabricating jigs, and it’s all complex measurements.

And there was a really great one I liked on the, you know, the elements of turbochargers, and principles of supercharging for beginners, and things like that. But then it’s also these road tester, a fundamental staple. The American car with the European look, getting back to his theme. This is the Ferrari 365 GTB4, which sits right out of his office.

We have one of these at McPherson. It’s really cool, you can come sit in it if you want. But my favorite road test of Road and Track was in 1970, April, where they did the Sopwith Canal, complete with Snoopy. And this is another attribute that neither Christy nor Luke talk about much, but the vision of this was to be like a New Yorker.

This was going to be sophisticated, it was going to be humorous, it was going to be clever, it was going to be edgy. But nonetheless, there’s no children. [00:47:00] Supercharging, fundamentals, technical diagrams. There’s also intergenerational content that’s generated by road and track. For example, cross country in a Morris Minor in September of 1953.

So we have an intergenerational image. Here we have an article of road testing the Jeep. And there were three images that included children watching out of the window. Letters to the Editor. Actually, there was a surprising amount of the child images were in the Letters to the Editor. They weren’t actually in what the publisher wrote.

They were in the letters. People writing, well, when I was a child, and they were trying to connect their intergenerational experience to Rodin tracks, so the readers were providing it, in some sense. And then, here’s women’s live in the automobile, Brockbank, and that’s about it, there’s not many images. I’ll give you some more quantitative analysis in just a minute.

Watkins Glen, as I mentioned, also has some images of family. Now, advertisers intergenerational images. The Morris Minor, here we have a family. With the Morris Minor,

Audience: and oddly [00:48:00] enough,

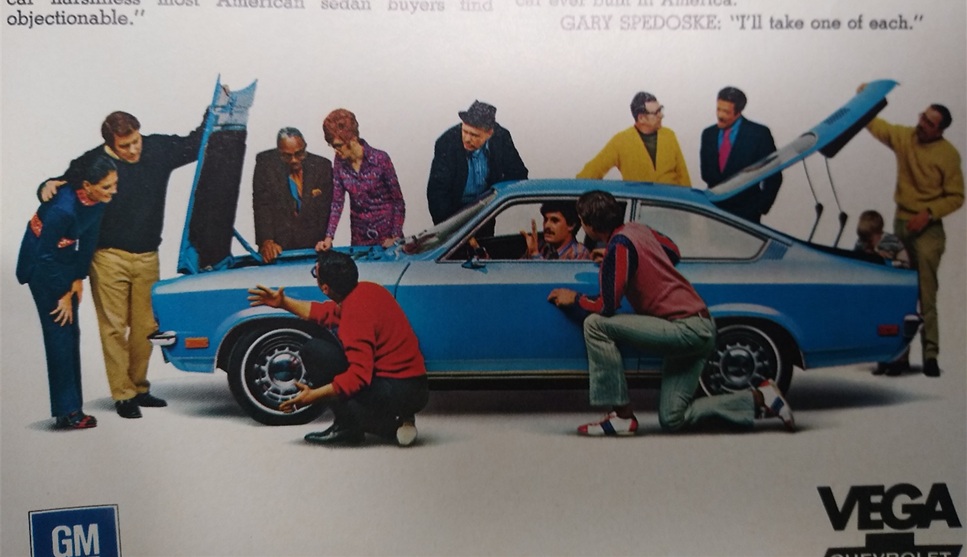

Ken Yohn: it was European cars that were advertising. And Road and Track were the ones that were actually providing intergenerational images, which is kind of interesting because that was not the car that John Bond was defining the magazine as his target.

He was not talking about family cars, but it was the family cars that advertised. The world’s greatest performer, the Citroën. And this is funny because this is not my idealized French family, but nonetheless, there’s a Citroën ad. Opal GT by This Is GM, but you can see a child looking longingly. And then we have another Vega ad with a small child in the corner, but there’s not much.

This was the single largest source of any children images, was this one ad, which appeared three times, and kind of screws up my data. We looked at a lot of road and track. I read like 8, 000 pages of road and track, I figured out later, and we all went that, and then maybe a little bit more, trying to pour through these and find these trends and patterns, and I never feel like I’m doing my job as an academic if I don’t get to draw at least one graph with lines on it.

So, there’s the first whack [00:49:00] at it, and then this is by year. So 53 to 54, and it’s normalized to be per 1, 000 pages. So per 1, 000 pages, an average of 5 times per 1, 000 pages is their reference to the next generation. And within the content provided by Don Bond, there’s an average of 3 images from the publisher per 1, 000.

There’s no intergenerational transfer intended. It’s not a criticism, it’s an awareness. That’s his target, his and her target, because they’re partners in a way. It’s a kind of conclusion of some of the things that we like about how we approach this and why we like embracing this kind of intercultural framework.

One, it’s really agency centric. It really focuses on the specific decisions that leaders or members of an organization or society make, the decisions they make. At the same time, It’s balanced with a really complex exogenous. So whatever changes that happen in the world, you begin to ask, okay, who responded to it, and how did they [00:50:00] respond to it?

Was it the community of Watkins Glen that was responding to these changes in the dynamics of how Watkins Glen racing was working? So this question of who is making what decisions and how they’re acting on them in a world where We are dealing with changes in technology, and economy, and politics, and environment, and ideology.

And all these provide the exogenous context for agency. It’s a dynamic model where you have change emerging from definitions of individuals. And then the breadth and complexity of the kinds of questions you can ask if you’re identifying a research agenda brings in, like, the whole circus tent, the whole shebang of the study of the development of a single vehicle.

versus the question of someone’s identity compared to the economic forces that shape the sociological forces that make NASCAR Nation different from Gentleman Racers. And all these kinds of questions that we want to ask really make sense for us to approach with this kind of methodological perspective.

Christy and Luke and I [00:51:00] would like to be available for a couple minutes if you have any questions.

Kip Zeiter: I think Road and Track came before Car and Driver, but I know when I was growing up, those were the two magazines that I had to get every month. Christy, I swear to you, if I ever bought a Playboy, I just bought it to read the articles.

Honestly. Anyway, do we have questions? Actually,

Ken Yohn: that would be a remarkable magazine to study as a comparison. Playboy compared to what was happening in Road and Track would be an extraordinary Next year? No. Can I help

Kip Zeiter: do the research on that?

H. Don Capps: This is a good framework that could be applied to a number of the periodicals that have shaped car culture. That we talk about and talk around. And this is a very interesting way to do that. And I like the framework that you’ve established. Looking at the publisher. You could go to Sports Car Illustrated, which became Car and Driver.

And you could start [00:52:00] looking at those relationships. And you could go to other, focused on racing. Paul Achtman, for instance. And On Track, and all those things. That’s a very good framework. I really appreciate that. This, this really opens, I think, some doors that you pointed out, Ken. And Luke and Christy to further work as an area, I think, that here in academia, we can really open some interesting aspects up that we really haven’t looked at very closely.

So thank you very much. I appreciate that.

Luke Chennel: One of the elements of intergenerational transfer that I wanted to identify and did was the transfer of David E. Davis. Because he started and wrote the track in 1955, and then of course goes on to transport Sports Cars Illustrated into car driving. And I think there, again, is a tremendous amount of work to be done in that vein.

Bill Gillespie: Thank you for bringing up Stan Mott’s Sensational Cyclops. I haven’t thought of that for years. I used to love that cartoon when I was a kid, and that was almost the first thing I went to in Road and Track magazine, and I [00:53:00] was just struck when I saw the picture of the Cyclops car. The similarity, To R2 D2, and also more recently, the Minions.

There’s some kind of comparison there, and it just makes me wonder if they were derived from Stan Mott’s cartoon car.

Audience: A big concern that I’ve been reading about is how to keep and encourage, you know, younger people to get involved in the hobby. Can you talk a little bit about what automotive publications such as Hagerty and others are doing now to ensure that?

Ken Yohn: I know that Hagerty has actually made a concrete effort and began partnering with us about Fifteen years ago, there was a forum called the Collectors Foundation that was trying to look for the next generation of collectors. And so, Hagerty has made a very intentional effort, placed a number of grads with them where they were trying to produce content, whether it was YouTube channels or article series that were written by [00:54:00] young enthusiasts, for young enthusiasts.

So, Hagerty is one of the places you can look as part of their business model. As far as other journals and things, I think that would make a great thing to maybe pass the mic around if you had a minute because there’s probably some people who have some really great answers about where that happened. I can tell you, of the meetings and conferences I’ve been to in the last five years, it’s the question that everybody is asking.

Luke Chennel: I might speak just in general about Uh, that being part of the motivation for this project, because certainly that question comes up at every event I go to. And I think the reason I was so interested in researching Bond’s definition of car culture is that that process of having young people involved is not the process of using Bond’s model of car culture.

Young people are enthusiastic about cars, but they have their own dimensions and their own paths that they want to take. And trying to force an intergenerational approach on them is just simply untenable and simply will not work. And so, there are plenty of forms of car culture out there today. It’s just that we need to think more broadly about what that means [00:55:00] to young people.

Ken Yohn: Uh, let me dovetail on that. The car culture is alive and well where we live. It’s young people everywhere who are crazy and passionate about the car. But, It takes a lot of listening on our part because they come for reasons different from what we’re ready to provide. And so we are in a constant metamorphosis at our institution, trying to figure out how we can dovetail technical opportunities in space to what the next generation views as car culture.

And so it has to be something that’s in motion.

Chris Lezotte: Looking at both Christy’s and Ken’s portion of the presentation, we can sort of understand why women were portrayed in a certain way during this time, as opposed to car guy culture, because, you know, the Association of Women in Cars sort of devalued the cars.

But I’m a little perplexed as to why you feel that they were so adverse to representing the next generation. Do you think it made it too Family oriented, too feminine, or was there some other reason?

Ken Yohn: My theory of that is that the reason you’re here for the car is [00:56:00] because you had an experience that made something significant in your life.

It tied something together for you, and it was part of your meaning. And so, you’ve come to understand car culture from your very personal experience that’s dramatically different from the next generation. And so, they will find their meaning in a car in a way that’s different. And so, we’re just bound by our life experiences in a way that means we have to intentionally set aside our beliefs and listen and let someone else tell us what car culture is.

That’s my suspicion.

Joe Schill: We’re talking a lot about the different ways that younger generation is interacting with car culture. Personally, I’m a little confused about what that is, what the differences are. And in my mind, I’m thinking the movie American Graffiti versus Fast and Furious. I mean, is that what we’re talking about, or?

Ken Yohn: Yes, you are. You’re talking about Tuners and Bokazuka, Japanese cars. And you’re talking about Grand Theft Auto and you’re talking about all kinds of connection points as gamer societies and the way they connect across the [00:57:00] relationships and it has to do with the scarcity of space that’s available to work on cars, which is something we just assume.

And so it is some demographic and physiological things about the dimensions of the interactions. It’s about the solitude of music, where every person is their own music generator, where we grew up in generations where that was a connection, touchstone. And so it’s actually this whole complex set of technological changes that creates a very individualistic experience, different from ours.

Kip Zeiter: That was terrific. I mean, we could spend the rest of the afternoon on this, but I just want to thank you very much again for coming out. Please, a round of applause for all of the Pearson people. This episode is brought to you

Crew Chief Eric: in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve motorsports, spanning continents, eras, and race series.

The center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world. The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share [00:58:00] stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events.

To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives. org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like [00:59:00] to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig mutants, gumby bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motor sports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Introduction and Overview

- 00:26 John Bond and the Rise of Road & Track

- 02:24 Luke Chennel’s Personal Journey

- 03:51 John Bond’s Influence on Car Culture

- 07:13 Bond’s Vision for American Sports Cars

- 10:19 The Role of Racing in Car Development

- 15:07 Kristie Sojka on Gender Representation

- 23:56 Advertising and Gender in Road & Track

- 31:56 Disappointment in Female Representation

- 32:41 Dedication to John and Elaine

- 33:01 Ken Yon’s Anthropological Perspective on Car Culture

- 34:12 Exploring Car Culture Through Different Lenses

- 37:01 Defining and Undefining Car Culture

- 43:11 Intergenerational Transfer in Car Culture

- 50:58 Q&A Session and Final Thoughts

- 57:34 Sponsors and Closing Remarks

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App: |  |  |

Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)