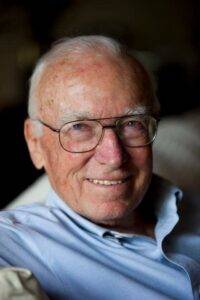

Gordon Eliot White has written seven books on the history of American open-wheel racing, including a history of Fred Offenhauser and the Offenhauser racing engine. He has served as the unofficial historian of the Harry A. Miller Club and as curator and archivist of more than 12,000 drawings, tracings and blueprints of Miller’s cars and engines, as well as of thousands of documents covering the history of American racing since early in the 20th century. His presentation will address Harry Miller’s impression on American racing as well as how aficionados rediscovered him after he had been all but forgotten and, over the past 40 years have un-earthed and restored many of his cars.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Bio

- Notes

- Transcript

- Livestream

- Learn More

Bio

Gordon Eliot White is a retired newspaper correspondent who covered Washington, D.C., Europe and the Far East for the Chicago American and other newspapers for 34 years. After he retired from news-paper work he became the Smithsonian Institution’s auto racing advisor, following a sport he had enjoyed since 1939.

Notes

Transcript

[00:00:00] Hello and welcome to the Gran Touring Motor Sports Podcast Break Fix, where we’re always fixing the break into something motor sports related. The following episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce and the Arts Singer Family, Harry Miller, the Man and the Cars by Gordon Elliot White.

Mr. White is a retired newspaper correspondent who covered Washington DC Europe, and the Far East for the Chicago American, and other newspapers for 34 years. After he retired for newspaper work, he became the Smithsonian Institution’s auto racing advisor following a sport he has enjoyed since 1939. He since has written seven books on the history of American open wheel racing, including the history of Fred Offenhauser and the Offenhauser Racing Engine.

He has served as the unofficial historian of the Harry A. Miller Club, and as curator and archivist of more than 12,000 drawings. [00:01:00] Tracings and blueprints of Miller’s cars and engines, as well as thousands of documents covering the history of American racing since the early 20th century. His presentation will address Harry Miller and Miller’s impression on American racing, as well as how aficionados rediscovered him after he had been all but forgotten and over the past 40 years have unearthed and restored many of his cars.

All right, folks. Next up we have Harry Miller, the man in the cars. By Gordon Elliot White. Thank you Bob. And, and good morning. It’s nice to be back in w Watkins Glen. I first visited here in 1951. In 1952 when they were running the, the races on the streets of Watkins Glen, and as I recall, they had the Queen Catherine’s cup and I was just totally, also had the Seneca Cup and then the Grand Prix was the piece de resistance.

I was a freshman at Cornell in 1951. And a race fan, which [00:02:00] led me to come over here to, to watch the races. While I was at Cornell, I ran a few rallies with my hot rod, one of which I actually won to the amazement of my mostly sports car competitors. My first photos are, are Harry Miller won with his, uh, nutting, one cubic inch straight aid engine, supercharged in the second with a supercharger.

My subject today is Harry Miller and his legacy. Miller built both racing cars and engines, and his engine designs dominated American racing for nearly 60 years later. They were known as often hours engines, but they were based on Miller’s design and general engine architecture. They would’ve lasted longer in Indianapolis if the supercharge of boost pressures and not been limited to protect the.

Competing four can’t Ford Engines, which couldn’t take as much boost as the offing Griffith Boesen has described Miller as quite simply the greatest creative figure in the history of the American racing car. Harry was born in Menominee, Wisconsin, son of German [00:03:00] immigrants. He had very little formal schooling.

Menominee was a lumber town, and he learned mechanical trades on steam engines and other heavy equipment in the lumber mills. He left Wisconsin to seek his fortune in Los Los Angeles working in a bicycle shop. He took correspondence courses and various mechanical subjects, which was the only technical training he ever had.

At one point, he worked as a foundry foreman where he learned the art of casting, which became very important in his life. Later on. 1960 went to work for the Senil Company and wrote as a mechanic on that year’s osen be entry into Vanderbilt Cup races on Long Island. Os didn’t do very well in the Vanderbilt Cup and Harry returned to Los Angeles eventually setting up a shop to produce carburetors of his own design.

Patented several designs and they were initially used as aftermarket carburetors on passenger cars. The Miller Carburetor, however, turned out to be quite successful for racing cars. [00:04:00] Led Miller to do custom work for many of the racers. The Miller Shop became the winter headquarters for many of the racing people, and he had customers including Barney Ofield, Bob Berman, and Dar Aria Resta, which at that time were the top people in American racing.

As Miller built racing equipment, his design work followed the empirical habit of Americans learning by experiment. Much as had Thomas Edison, who designed the light bulb by trying out, I think 200 different things for his filament. And Henry Ford, neither of whom had university educations by comparison in Europe at the time.

Trained engineers led most of the, uh, technical development. And uneducated race drivers jus go. George below and Pu Elli would would call Le Charlas when they designed the first overhead CAM convention for pia. Much to the disgust of the trained engineers that worked for Pia go drove an overhead [00:05:00] camp Pia to win an Indianapolis in 1913, Bob Berman bought it.

Blew the engine and race at San Diego and took the remains to Harry Miller to have it rebuilt. And he, Rick Backer also in his terms, unloaded his broken down puo on Miller, calling it the major mistake of my racing career because he made a tremendous car out of it. Miller, in the process of rebuilding peso’s, educated himself in the best European engine practices, the first complete car that Millerville.

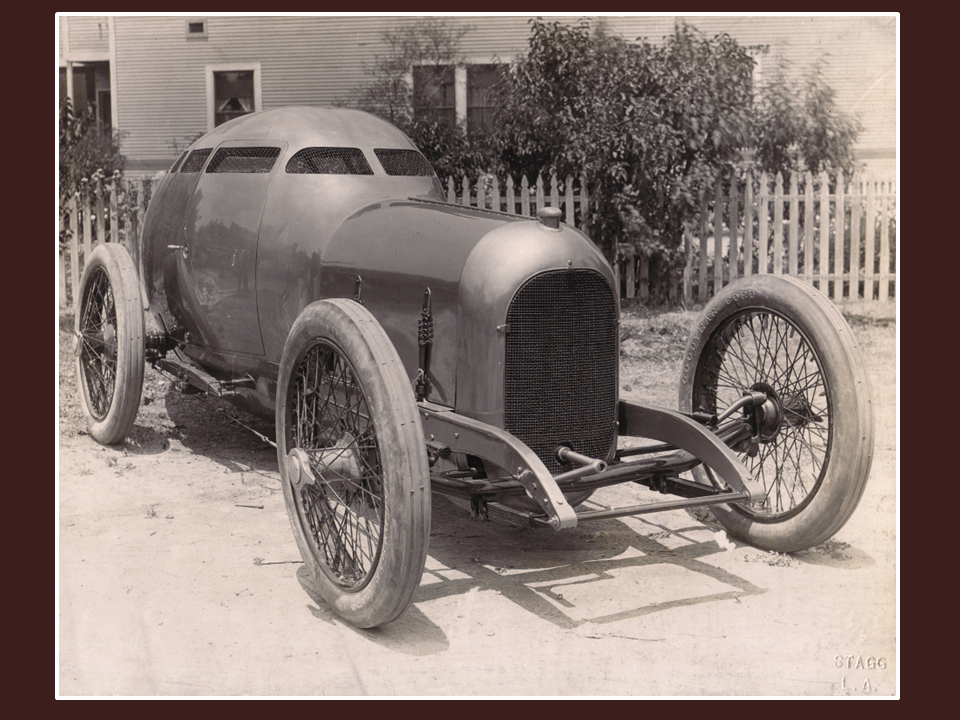

It was called the Golden Submarine. It had carried one of the engines that he had designed. Engine was also perhaps to go into an aircraft, and Miller hoped to sell those engines either for racing or airplanes. In 1916, Barney Oldfield had Miller built this radical enclosed racing car, powered by that engine.

As I say, it was painted in Gold Locker and became known as the Golden Submarine. Bull Fields drove it in a number of races. It was not a mess league successful, but it won a few races at Springfield, Illinois. [00:06:00] He crashed and the car caught fire, and so after that, Barney cut off the rest of the body so he wouldn’t be trapped in it.

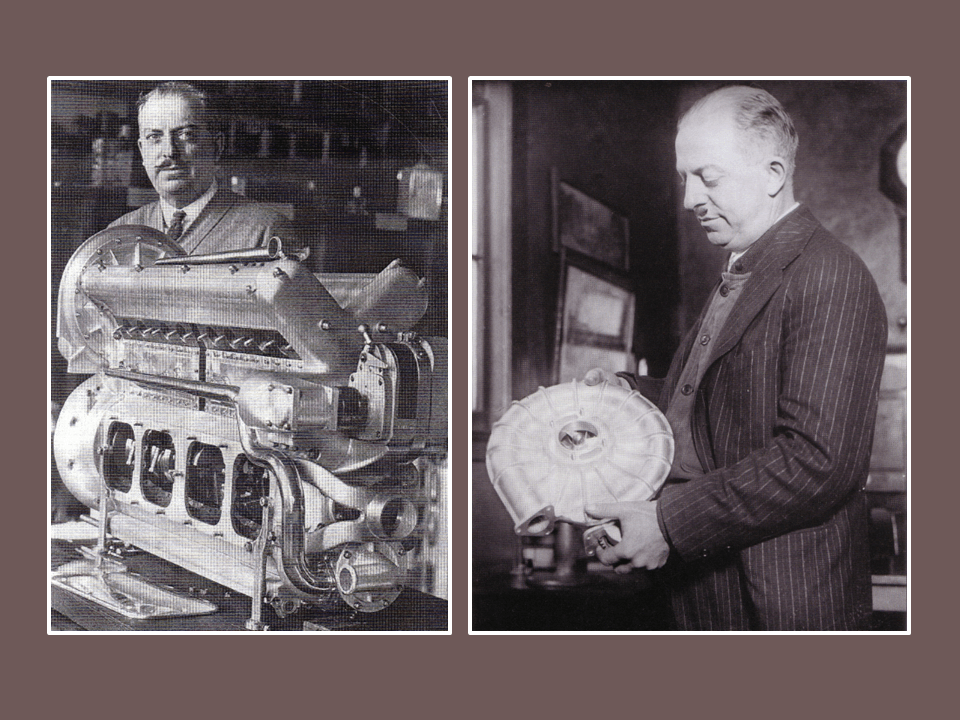

From the Golden submarine, Miller went on to build a few more experimental racing cars. The best of them being the t and t. After Leo Goen, who was the trained engineer and draftsman who came from Buick, joined his staff, Goen supplied the technical knowledge of a trained engineer. That Miller lacked, and he would go on to become the preeminent race engine designer in North America.

Somewhat earlier, Miller had hired Fred Orphanage as a machinist orphanage, had been trained in the, uh, railroad shops, and at the time, the railroad shops of what NASA became, it was the highest level of technical work and design in the country from the golden submarine. Miller went on to build a more few more experimental race cars.

In 1924, Miller Engine cars were entered in Indianapolis, but none of them qualified during the following year, Miller and Driver, Tommy Milton helped design [00:07:00] a uh, straight engine of 183 cubic inches. They embodied much of the engine architecture that remains through the life of Miller and Izer engines.

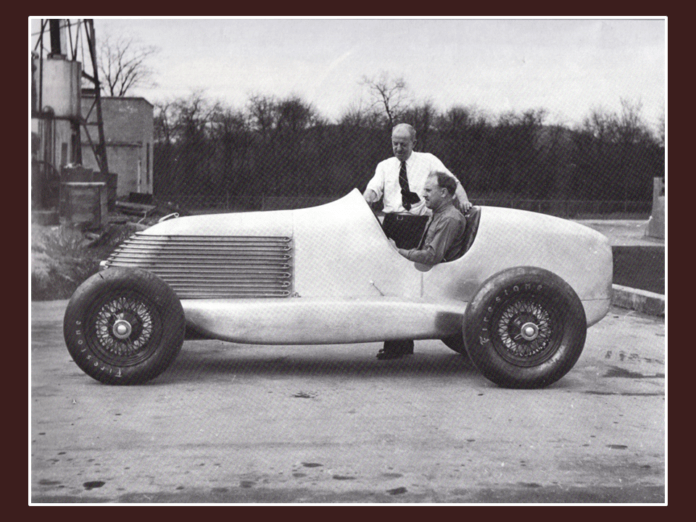

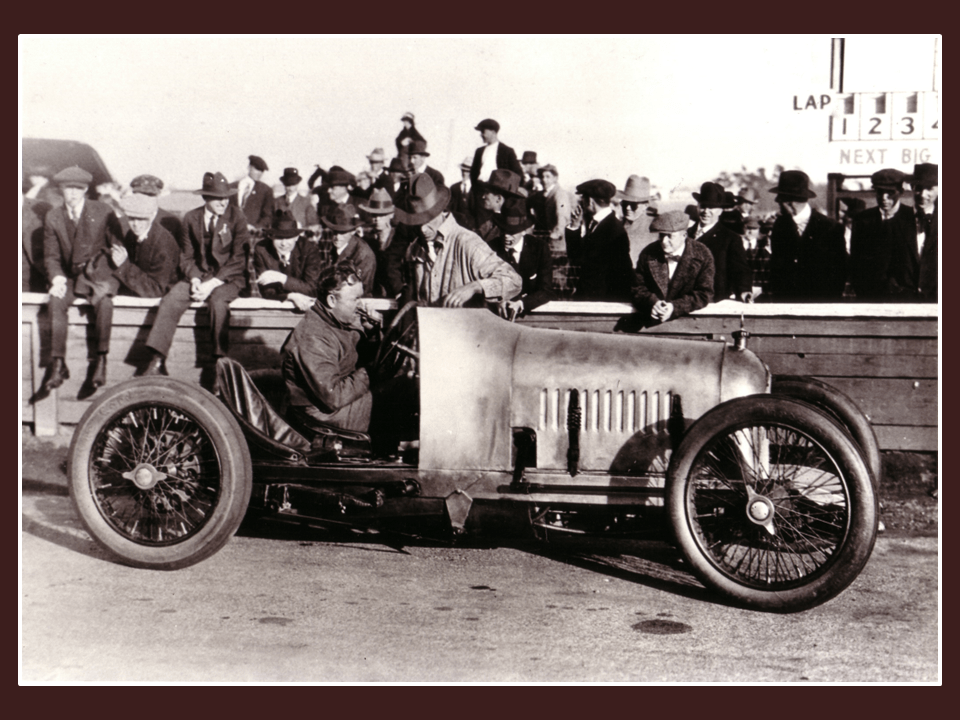

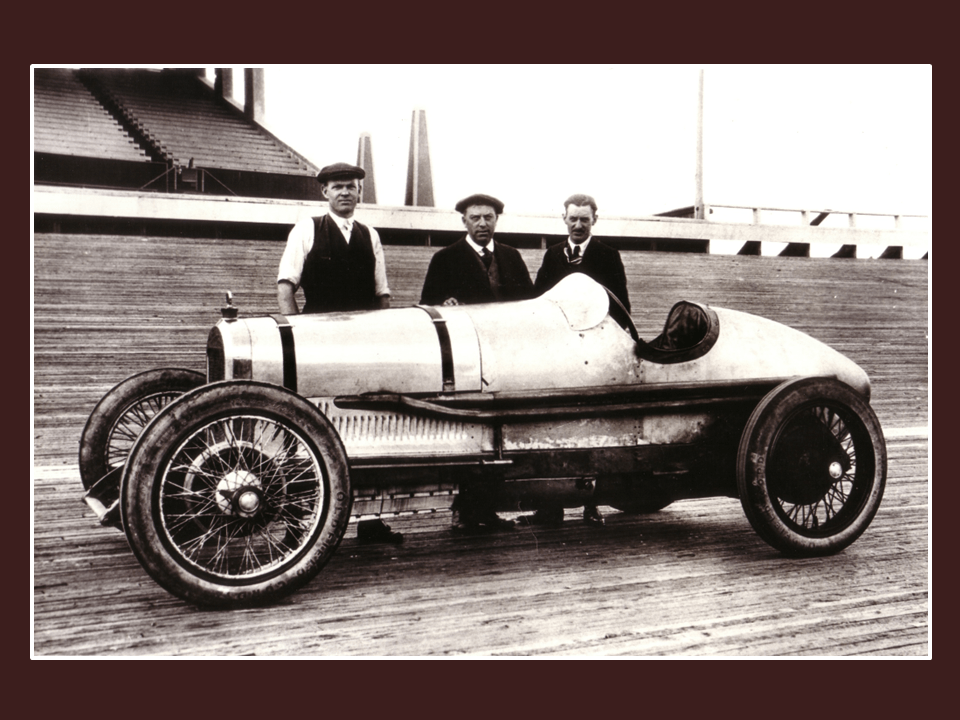

Ive qualified one of these 180 threes in India in 1921 and finished 10th, 1922. Jimmy Murphy qualified with a Miller engine and won the raids in 1923. Millers competed in several European Grand Prix. And they finished well, although they didn’t wanna race. This next picture is of a front drive, 91 cubic inch Miller car.

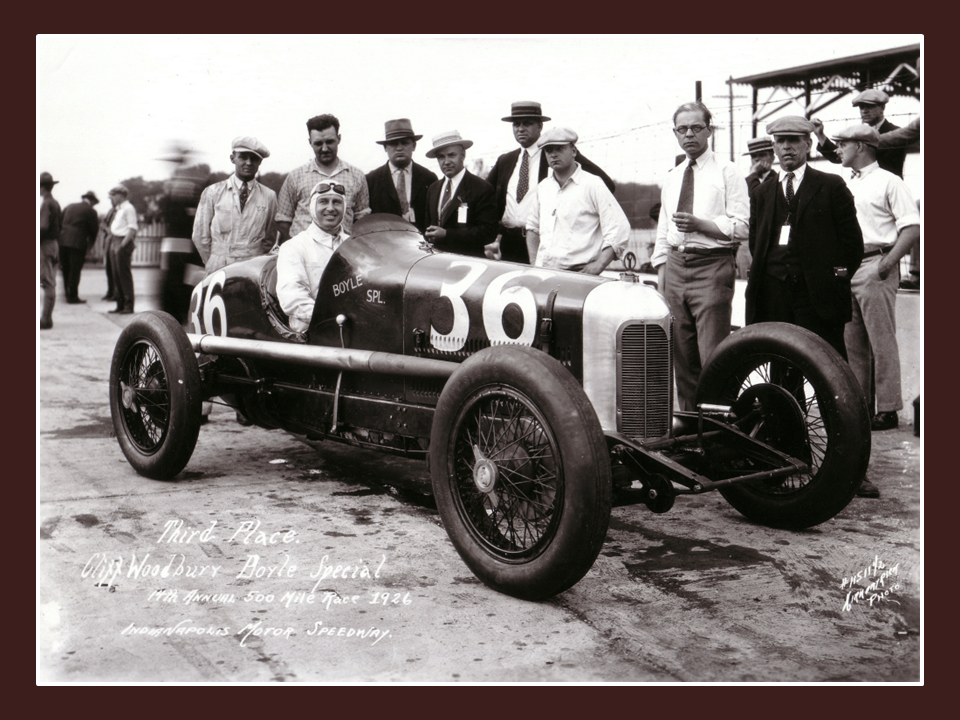

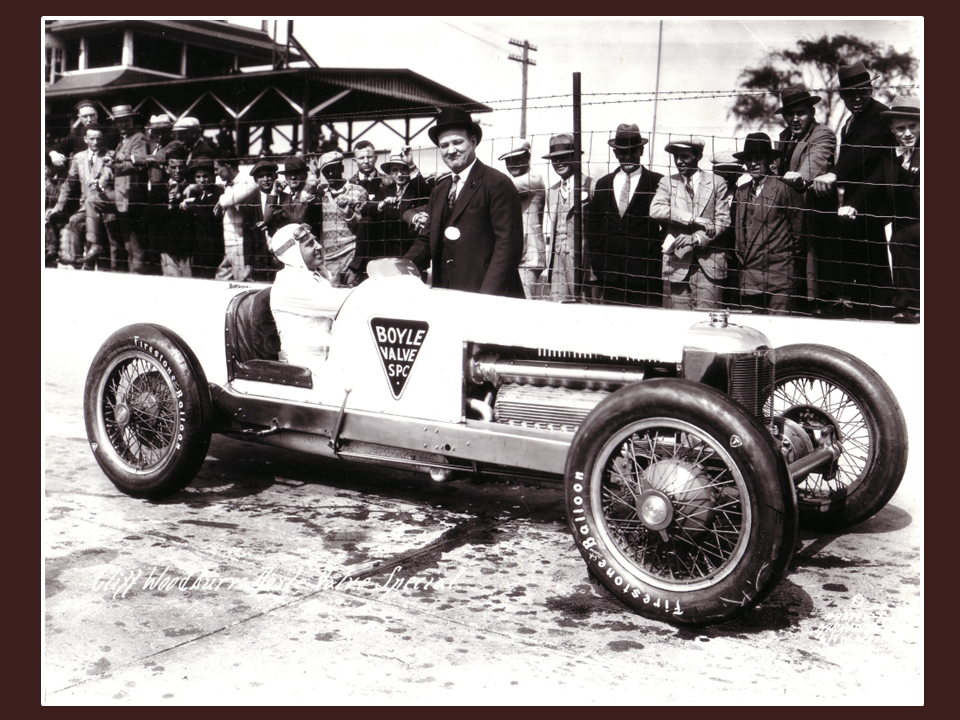

And the man in the background with the the bowler hat is umbrella. Mike Boyle Boyle was the business agent for the Chicago Electrical Union as his day job. And you wonder how he made enough money out of. Being the business agent to afford race cars, but that was Chicago through the rest of the roaring twenties Miller Engine cars would win five of eight races at any Indianapolis, even as engine sizes were reduced first to 122 inches and into 91 [00:08:00] inches supercharging.

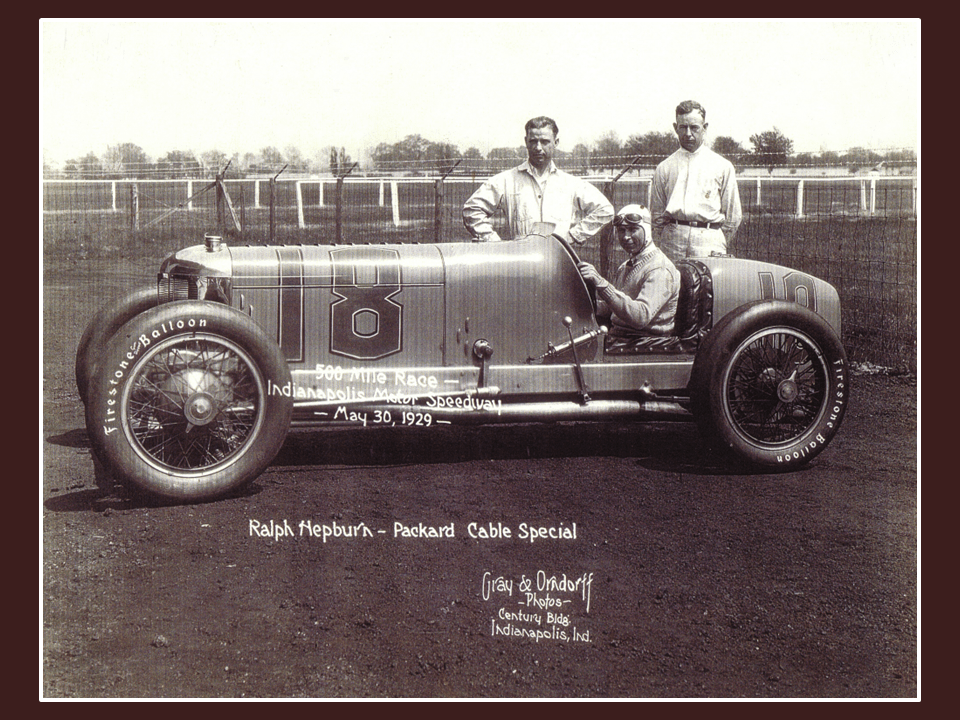

We used to increase the horsepower even while engine displacement were reduced. This is Ralph Hepburn in the front Drive, Miller 91. This is a car I will mention again later on. At the same time, Miller was also producing a four cylinder engine of 151 inches for racing boats. Eventually, a slightly larger forests produced for dirt track cars that are now known as sprint cars.

Miller engines were the top of the line of speed boat racing in the 1920s, and eventually band leader. Guy Lombardo would win the Gold Cup in a, uh, Miller Engine speedboat, which started out named My Sin, and he named it Tempo Fourth, by 1929, Miller was at top of the heap in racing, but his and the Dusenberg brothers, tiny 91 cubic inch engines had gotten a long way from the original Indianapolis racing, which was largely a stock car.

So the F taken off. This is a Miller 91 pistol, supercharged straight eight. [00:09:00] Actually, this piston is out of one of Leon Dre’s, uh, 1928 Front drive Millers. I got it, uh, when the Smithsonian took one of Dre’s cars in 1993, and it had been re restored by Bob Ruben, the donor. The change that Rickenbacker pushed through the AAA contest board led to what was called a junk formula.

They banned supercharges and allowed stock block engines 366 cubic inches quite a bit more than any of the Miller engines really were ever built. Miller engines continued to win and in Indianapolis, nonetheless in the early 1930s. Harry, Designed a series of innovative chassis powered by larger 230 cubic inch engine UN supercharged in accordance with the rules, but those are depression years, and he couldn’t sell enough two 30 s to keep his business going.

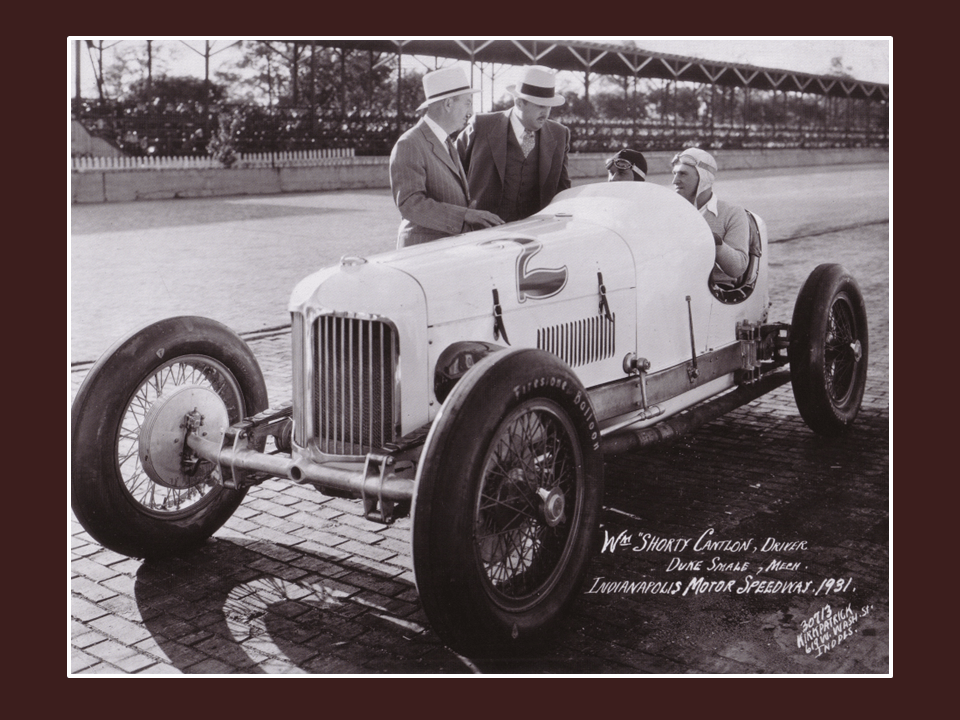

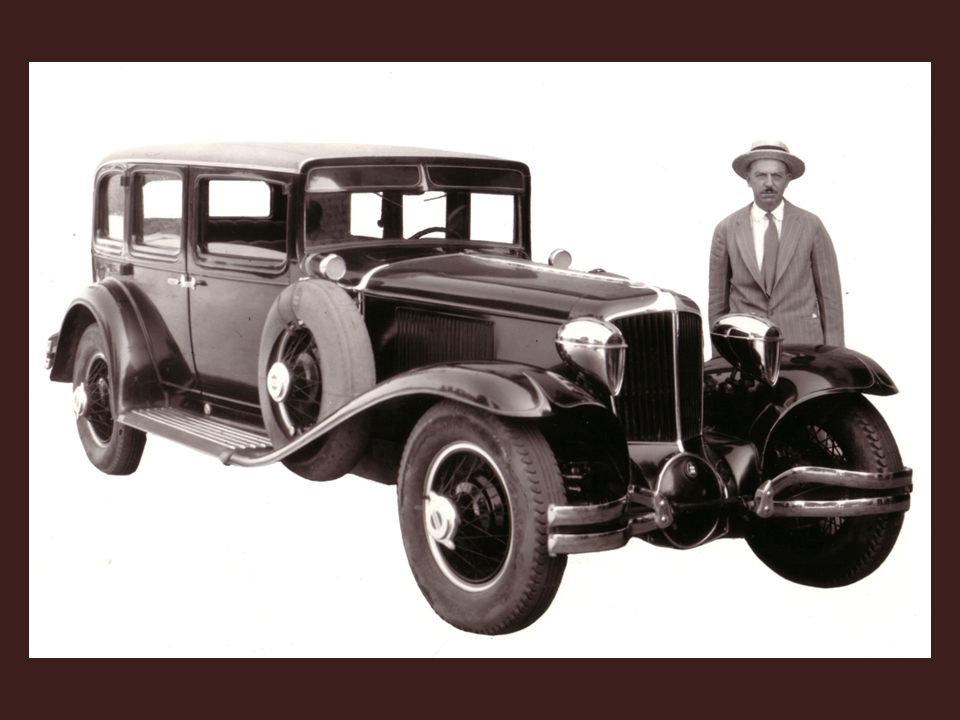

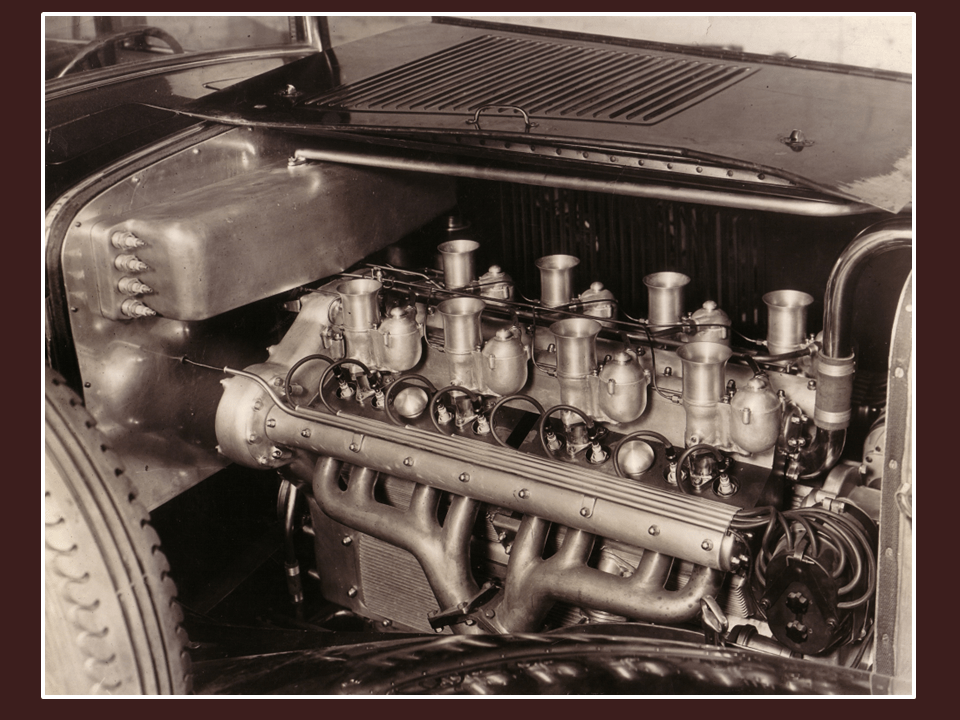

This picture is short at Catlin in one of the two 30 chassis with a 16 cylinder engine Miller engine in it. However, Harry got [00:10:00] into the, uh, custom passenger car business, which, uh, he couldn’t sell enno enough of them to keep his business going either. The next photo is of the engine, which I, I think this is a pretty impressive V 16 Miller engine, which later went into a a race car.

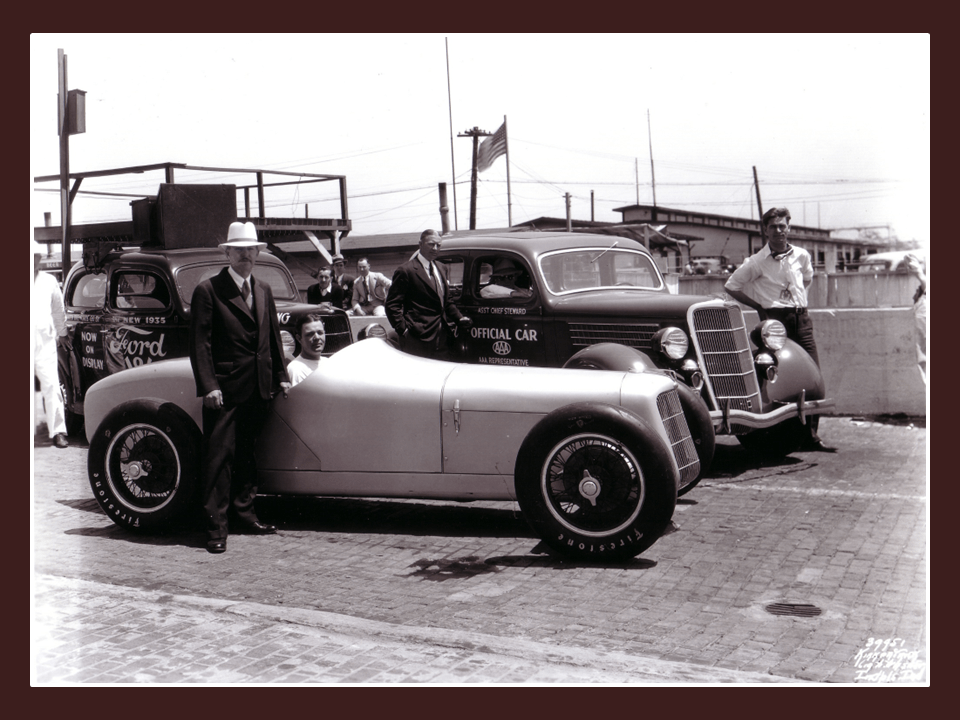

When Miller went bankrupt, he left Los Angeles forever. And although he was broke, he was still considered a genius by people who wanted, uh, race cars. This is a, a Miller Ford Preston Tucker was able to talk. Henry Ford in the, having Miller built a series of 10 race cars, very advanced race cars to carry the the new Ford BA engine.

Unfortunately, they started building them in March for a race in May, and they were not able to test them adequately. While they had some good drivers, Chad Horn was on four, were able to qualify, but all of them fell out of the race in 35, largely because of the inherent problem with the steering gear, which of course much [00:11:00] discouraged, uh, Henry Ford and he sequestered the cars for, for a while.

Eventually, they got out and were used in other ways. The unsuccessful passion card has probably put the nail in the coffin of Miller’s business and at the bankruptcy auction. Miller’s shop foreman Fred often has had bought most of the machinery and patterns and set up his own shop to manufacture both parts and complet engines.

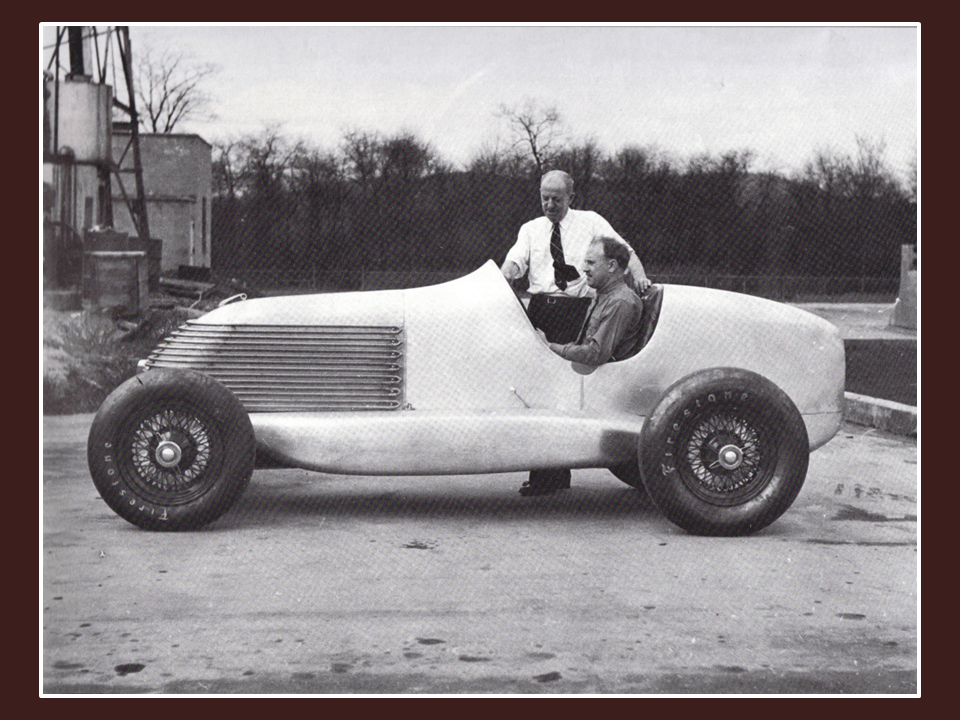

Eventually changing their name from Miller to often has it, although they were, of course, based on Miller Design. And next Gulf Oil hired Harry to build emissaries of race cars. Unfortunately, they specified that they run on Gulf Pump gasoline, which was not a very good idea because other people were running race cars, particularly in Indianapolis with uh, racing fuel, which made a lot more power.

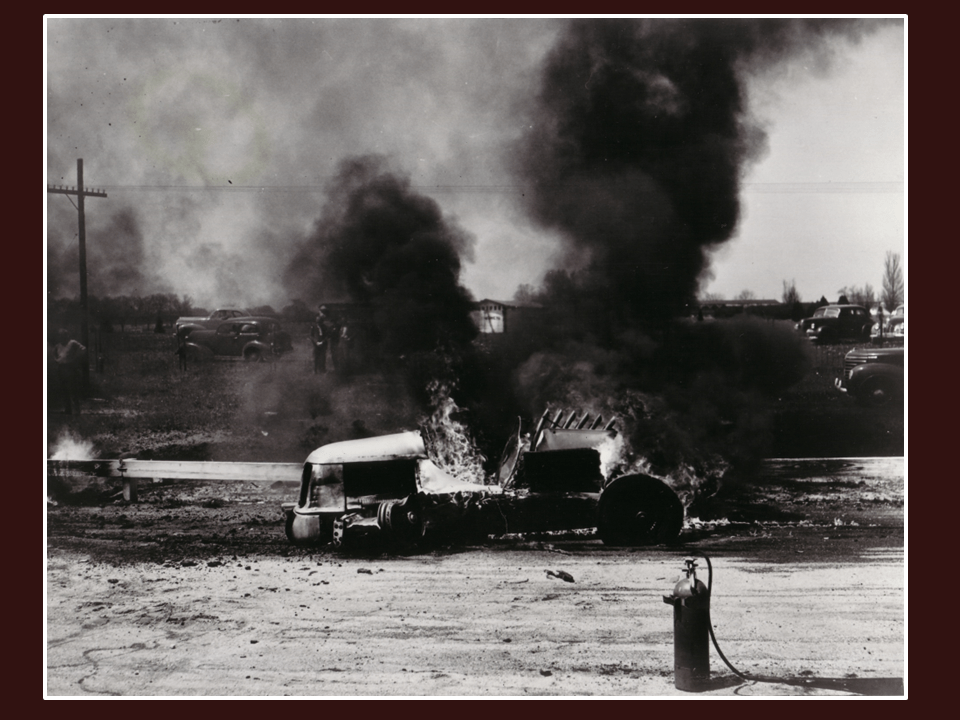

Harry didn’t have Fred or Leo to calm some of his flights of fancy. This car, you will see, has a radiator made out of chrome plated tubing that was. A mistake, it overheated [00:12:00] immediately and they had to replace it with, uh, rather ugly conventional radiators in the event they took these cars to Indianapolis, but they had problems of all sorts getting them qualified.

The fuel tanks were at the. Bottom of the frame there. Mark D thinks they’re an aerodynamic item. I’m not sure about that, but they were certainly a hazard because when they, A couple of ’em crashed. And the next picture is, uh, one that crashed, ruptured the fuel tank. The car burned up, killed the driver.

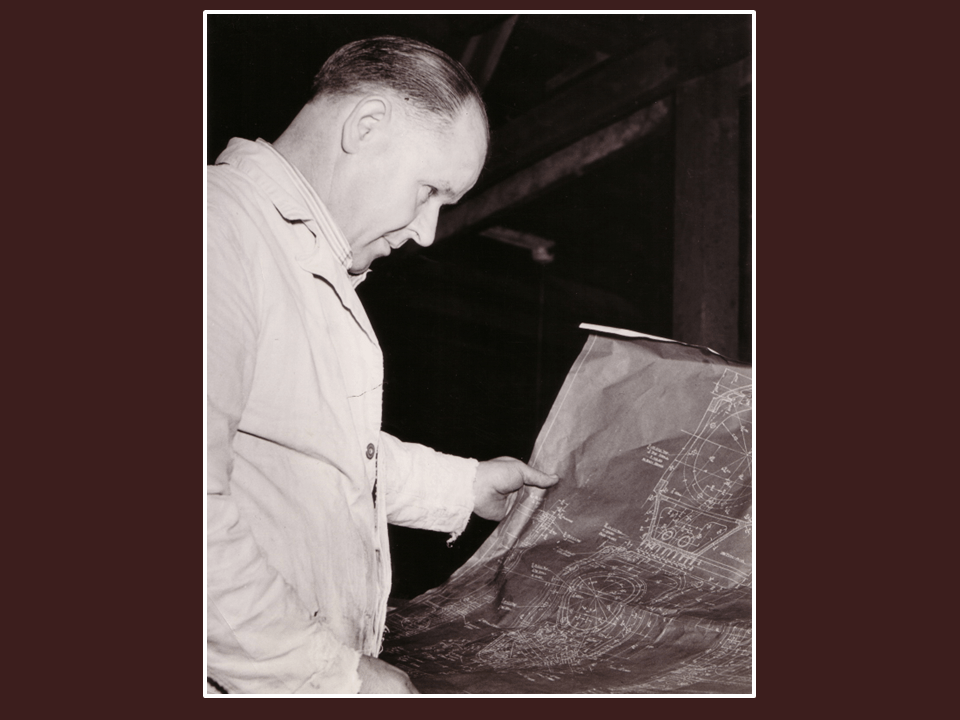

Who was George Bailey? His World War II approached Miller, moved to Detroit and designed both aircraft and marine engines for the military. Preston Tucker lured him into designing an engine for both an armed car and a fighter plane. But Harry didn’t have the engineering skill or knowledge to meet the Air Corps requirements for military engine.

He was still designing empirically by trial and error that didn’t suit the, uh, military. Harry was then living in Detroit and [00:13:00] he died in Detroit in poverty in 1943. Now this is Fred Offenhauser who had taken over producing Miller Engines in the early 1930s. Midgets had become a, a real force in racing, but they were generally powered by junk engines, motorcycle engines, and moved the sha along.

Several people decided they needed a, a professional racing engine. Often Hauser had Leo Goen essentially cut a Miller 180 3 and a half to produce a 97 cubic inch Midge engine. It was an immediate success till the late seventies. They put often Hauser and uh, had produced 450 of those engines. We’ll note some of the successes that.

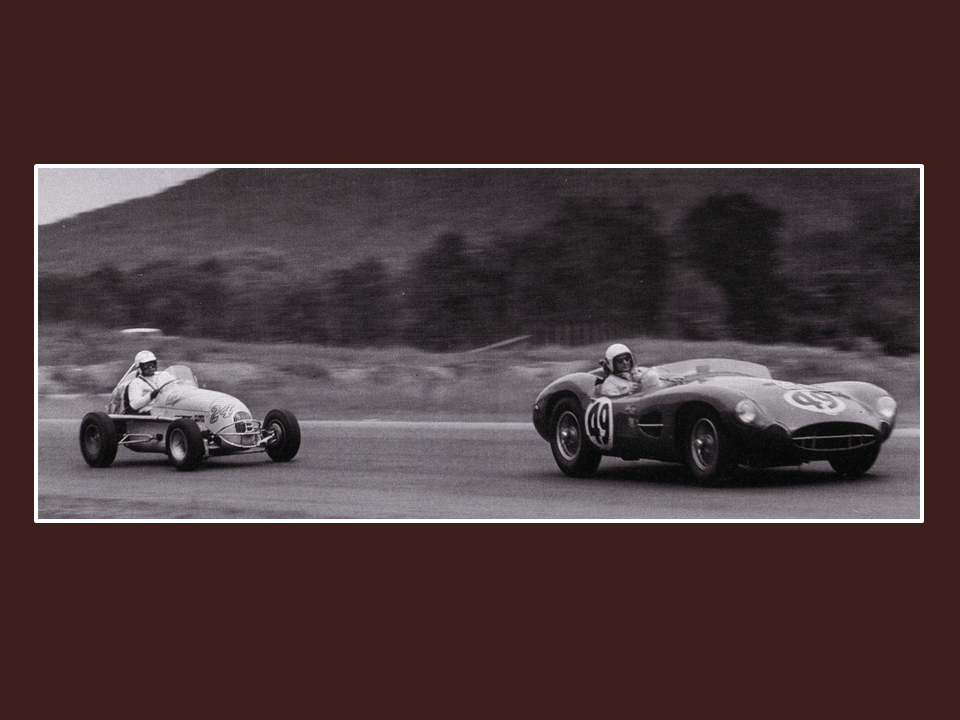

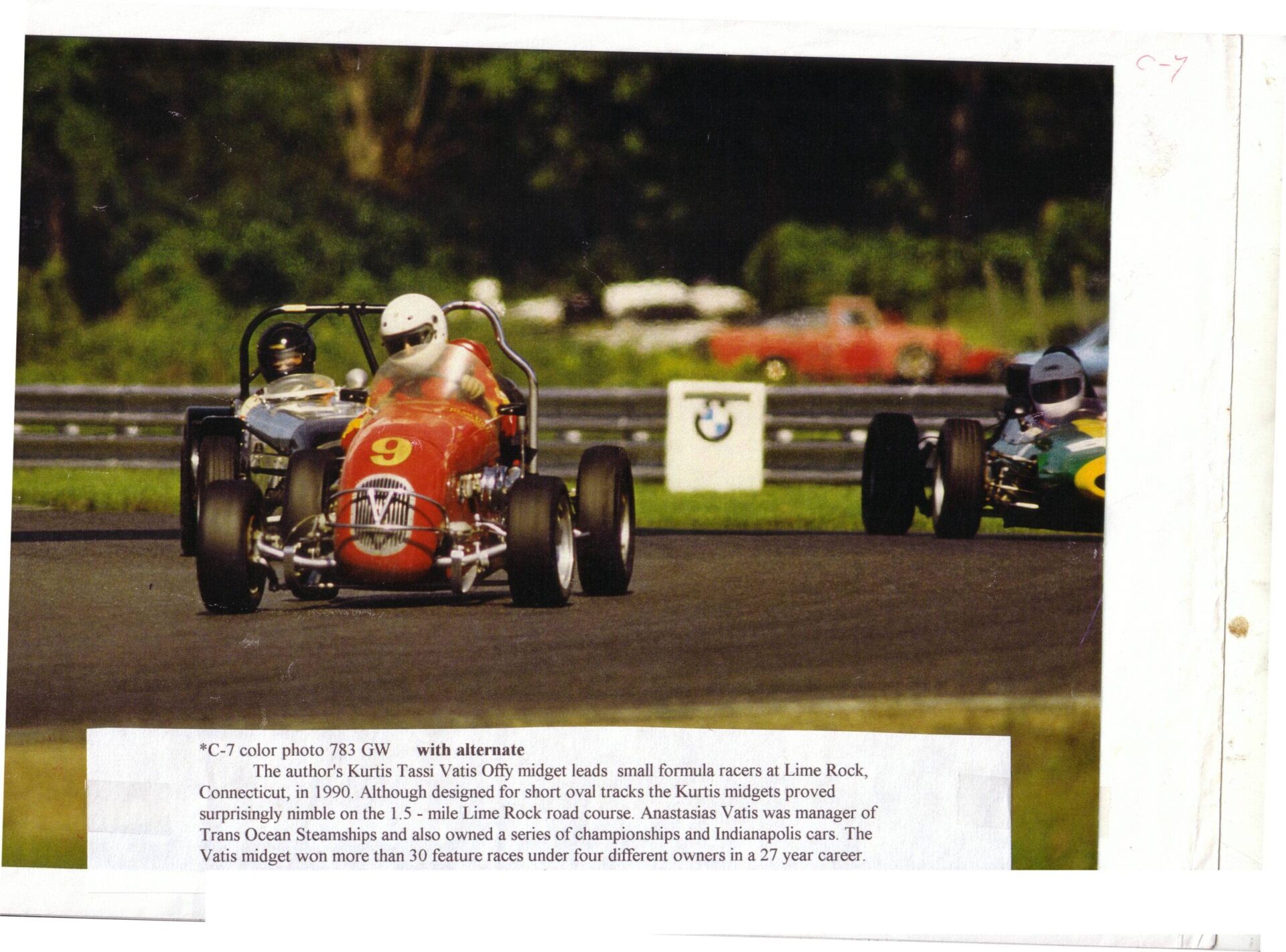

Of the orphanage arrange. 1959 usac, which replaced three A as the dominant sanctioning body in American racing, held a series of formula Libra races pitting midgets against sports cars. In the most famous of these held on the road course at Lime Rock, Connecticut, [00:14:00] Roger Ward, and an orphanage powered Curtis defeated the cream of the world’s sports cars.

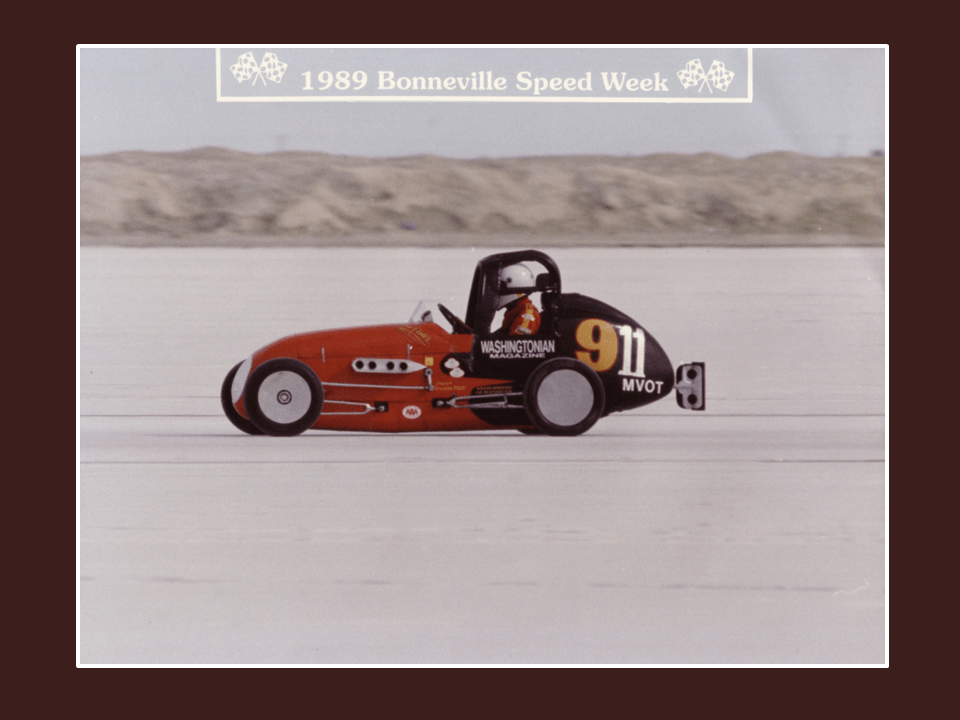

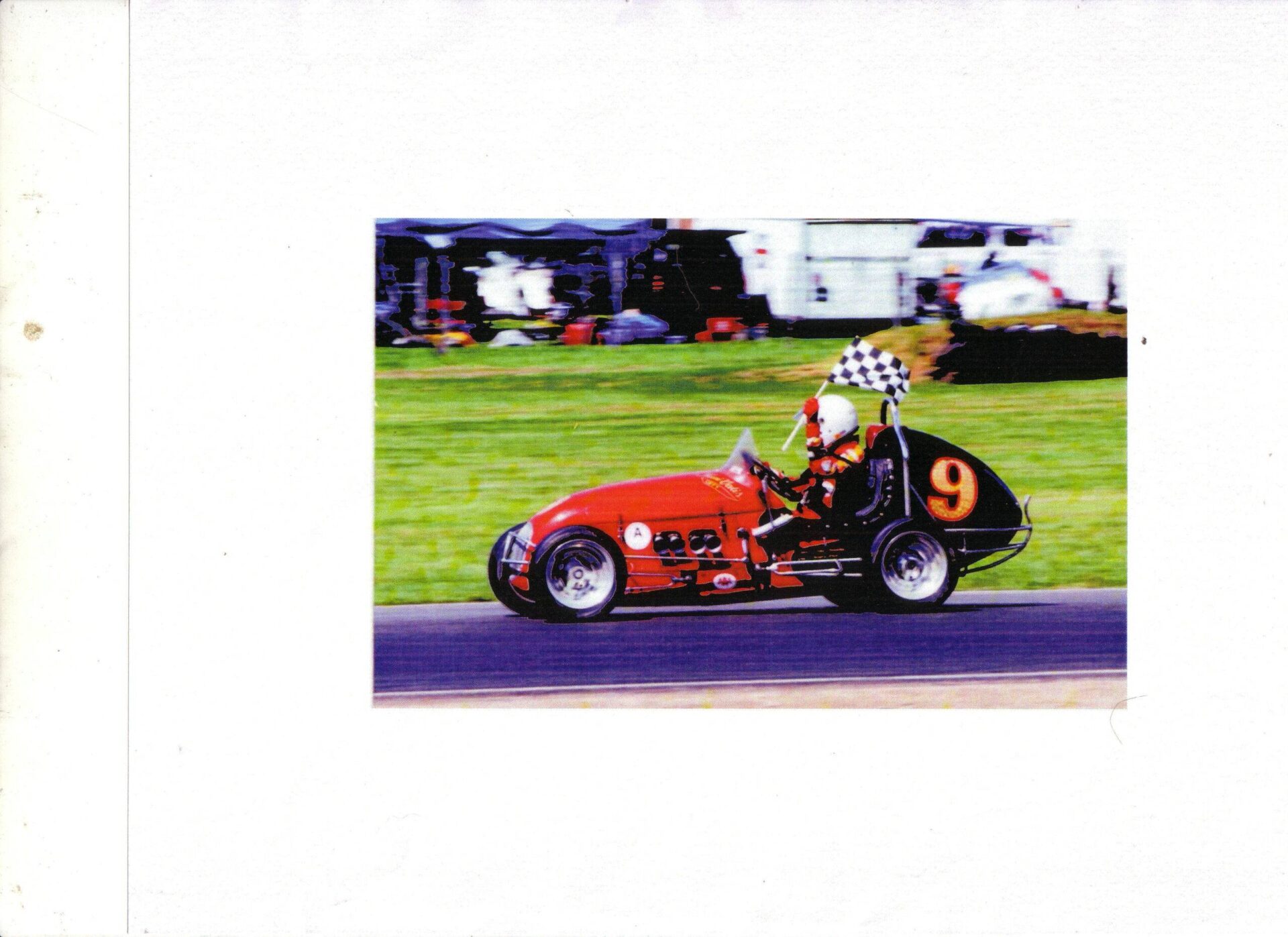

This is Ward and the Ken Brand Midget about to pass George Constantine in the Aston Martin d b R two. Shocked the sports car world that midget could could defeat them. And I had a little success with an offy midget. This is my car at Bonneville 1989, where I set a midget record of hundred 56.902. And then I set a an f i a two liter un blown record.

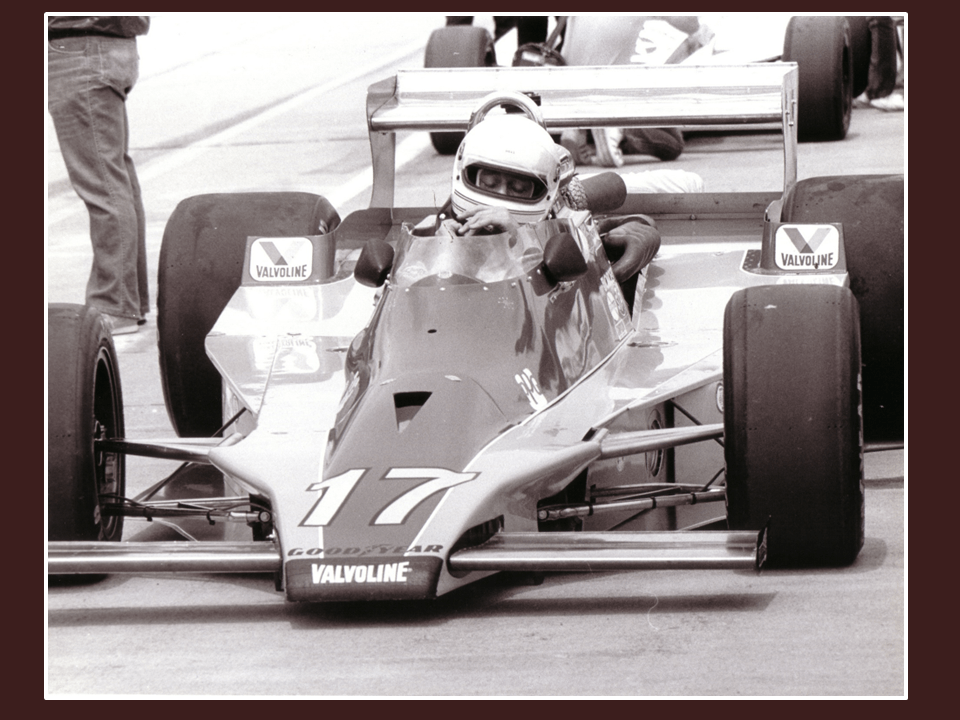

Well, 1 53, 198 probably the only car to set a speed record after winning top prizes of antique show car. The izer indie engines I say were penalized by not being able to run as much boost as they would’ve liked. This is, uh, Mark Anderson in the last offy powered car to be entered at Indy. He was in line put qualification run when time ran out.

And that was the end of of the Izer at in Indianapolis. This, by comparison, is [00:15:00] an indie off engine 270 cubic inch. As you can see, it’s somewhat larger than Millers 91. The first of the izer built Millers was a 2 55 cubic ends produced in 1935 for Kelly Patello who won the ND 500. With it that year, putting the orphanage or off the engine at the top of the list, a series of indie competitors.

Although Leo Gren said to his dying day that the engine was refer Miller. Well, the following 37 indie races, the engines known as orphanage 1 28. In fact, the five years in Indianapolis, all of the qualifying cars were offy powered. In 1946, Fred Orphan Ier sold engine business to Lou Meyer, Dale Trade, who continued to under the orphan ier name.

As I said, the awfully was displaced at Indianapolis by the T Camp Ford Engine, but it came back in the 1970s with Turbocharging to win five more. Five hundreds. The last awfully qualified came in 1980. This is, uh, a turbo [00:16:00] offy owned by RO of Als stat. As I say, it was in line of qualified but didn’t make it.

2 72 55 and later turbocharge off dominated championship racing for many years, and the smaller midget engine simply overwhelmed midget racing after World War II UN offy engine and occurs, chassis was so dominant. There was an event of any other car engine wanted to raise. The two 20 sprint car engine was the class on the half mile tracks as well though because it cost more than the, uh, modified model A engines, another passenger car engines.

It was in a minority 1957. The small block Chevy with many more cubic inches became competitive in the last year and off he won the Sprint Guard championship was 1959. As I said, Miller died in Detroit in 1943. Almost forgotten after the war. A few people remembered him or that the dominant orphanage engine had become life as a Miller.

It was not until a dozen years after Miller’s death that Griffith Ferguson had a sports Car. [00:17:00] Illustrated magazine began to write about Miller and his engines. And people began to appreciate Harry Miller. Leon Duray had taken his two Miller franchise of Cars to France in 1929 after the last Indianapolis race.

Before they were outlawed by the rules change, he sold them to Bugatti. They remained in France during World War ii. Borg discovered ’em. Their 1959 brought them back to the United States. One went to the Indianapolis Speedway Museum. By 1990, the newspaper I was working for had lost half its circulation and couldn’t afford me in Washington.

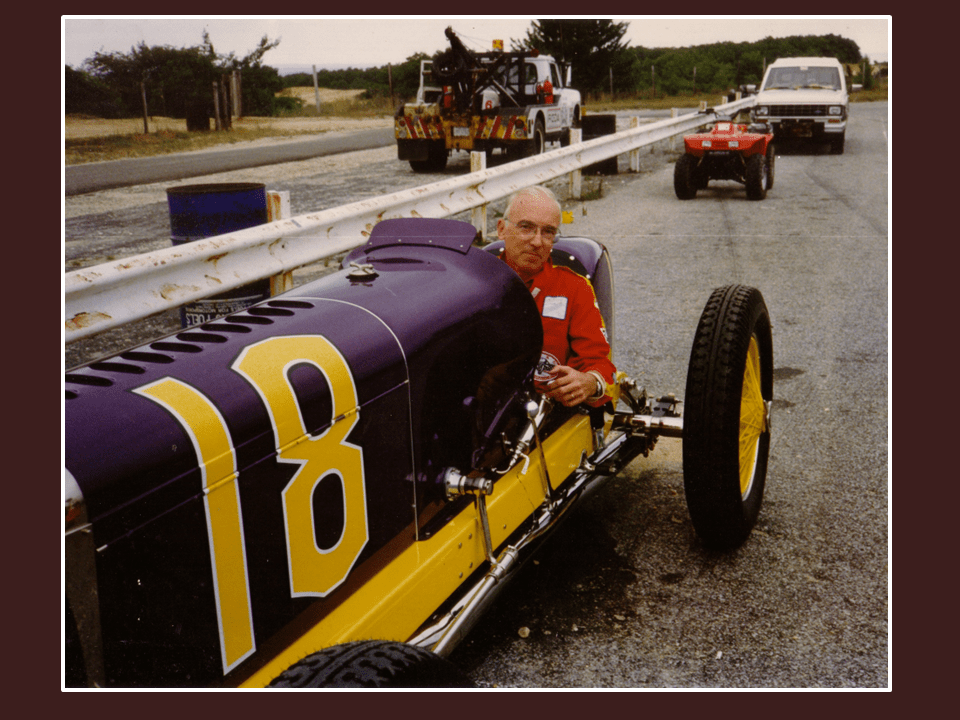

So I took early retirement, went to the Smithsonian as their auto racing advisor. This is a photo of me in the Dure car at Bridgehampton when I was trying to persuade Bob Rubin to donate to the Smithsonian, which he did in 1993. Boon’s writing about Miller generated a movement among a group of car collectors to find surviving millers and restore them.

In the early 1990s, mark Ds of Moore Park, California, [00:18:00] Chuck Davis of Chicago, Dave Elon of Milwaukee, and Bob Sutherland of Colorado, organized the Harry A. Miller Club, which each July hosts meet at the Mile Track in Milwaukee, where restored Millers and other front engine champ cars can be exercised at speed.

This is a photo of the, uh, field at Milwaukee with mostly Miller cars and engines. Many of Miller’s drawings and blueprints have survived for 25 years. I’ve maintained an archive of more than 12,000 such drawings, originals of which are out to Henry Ford Museum at Dearborn. By now, there are more Millers many put together out of parts, and how he built.

The event at Milwaukee in shows such as Pebble Beach, media Island, and Hershey Pay. Appropriate honor. Harry Armenia Miller, A Giant in American Racing. Thank you.

Do we have any questions for Gordon White? Gordon, you and I have worked together [00:19:00] for a long time. I’m interested to just comment. There are a couple of things that remain, you might say in question that I’d I’d like to bring up, but the, the first is that, Actually the design for the double overhead cam sh shaft engine, the, uh, 180 3 was a result of the frustration of Tommy Milton with, uh, getting dusenberg single overhead cam engines that he didn’t think were up to level.

But he did steal the, uh, specifications of the Dusenberg engines that brought them to Miller. Which, uh, produced, uh, the original double overweight came, uh, Miller, which then he began to win races with a car called the Durant Special. And, uh, eventually of course, uh, as I mentioned in my lecture, Jimmy Murphy and Harry Hartz got a hold of engines.

And eventually then, uh, cliff Durant build a, I think a field of five cars that were entered. I’m interested, and I, I don’t know if you’ve ever investigated this, but Jim O’Keefe and I, uh, [00:20:00] were working hard on this, uh, Question. And, and we believe actually that the first true full Miller racing car was called the Pan-American Built prior to the, uh, golden Submarine.

It’s never been fully accredited as such, and I’m, I’m wondering whether you have any comment on that. The final comment is just that, as been said, there is really a real cult of Miller lovers. Me being one, oh, I don’t own one. Miller’s achievements, at least prior to losing his company, were a result of competition that, uh, was from both Louis Chevrolet and Fred Oga and Dusenberg who introduced supercharging at, uh, the Indianapolis 500 and others.

It’s a fascinating era of American development in which. Tires, fuels and metals, lubricants, all of these things were in essence, developed in the board track era, largely by Harry Miller and the Dusenberg and, and, uh, and Louis Chevrolet. But [00:21:00] comment is, is rather too long, except to say that I’d be interested to know if you’ve investigated.

The Pan-American as a car, and whether or not indeed it was the first true full car built by Miller. From what I know, that’s a, an unfounded rumor that might possibly be true. It’s clear that Miller took advice from, uh, Milton and other drivers car owners. He didn’t do a lot of on track testing a little.

We have a few photos. Most of the testing was done in races and the things didn’t work. They came back to Harry and said, you gotta fix this, you gotta fix that. And that continued through often Arthur Meyer and Drake and Drake Engineering. But I, I’m not really aware of definite knowledge on the, uh, pan-American.

When did Henry or did he have any interest in aerodynamics in the streamlining of his cars? You could possibly say the Golden Submarine was an experiment, aerodynamics. It was certainly more aerodynamic than contemporary [00:22:00] race cars at that point. It did not prove to be a world beater as we saw Bernie Ofield be likely to be trapped in a closed car, took it off side fuel pods on the, uh, Gulf Miller cars.

If you look at them carefully, side pods there could be seen as an air foil. It was thought to perhaps Miller was designing them to give down, down for us. That’s as much as I’m aware of Sirius aerodynamics. Of course the front drive cars without a drive shaft under the driver allowed them to sit lower and they had less frontal area, so that was an aerodynamic advance right there.

Gordon, one last gentleman in the back asked, has any of the tooling survived often? Hauser or Miller, what have you? Not that I’m aware of. I’ve got photos of some of the Miller machine. Izer bought some at the bankruptcy auction in 33. He’s also said to have taken some out of the back door before the auction.

Myron Drake undoubtedly got some when they [00:23:00] bought out Fred Izer. I knew John Drake talked to him. I don’t think anything had. Survived from Millers shop. His machinery was run at first by overhead shafts. His machine shops were running those days. Eventually, they electrified some of the machinery.

Machinery from the late twenties was probably not really useful by the time that John Trach were out of business. Some of the patterns have survived. Bob McConnell has a number of patterns. Kendall Merrit has a number of patterns. Dean Butler had quite a few and he sold them to somebody in Troy, Michigan.

Unfortunately, during the Meyer and trach years patterns that were clearly obsolete were thrown away and some of ’em were burned up. A few people rescued some of those obsolete patterns, so I never have survived. So if you really want to cast your own Miller 2 55 block, you can do it. Gordon, thank you again.

Thanks very much.[00:24:00]

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motorsports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and comradery of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcome series researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race, drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The s a h actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into [00:25:00] the future.

For more information about the s A h, visit www.auto history.org.

If you like what you’ve heard and want to learn more about gtm, be sure to check us out on www.gt motorsports.org. You can also find us on Instagram at Grand Tour Motorsports. Also, if you want to get involved or have suggestions for future shows, you can call our text at (202) 630-1770 or send us an email at crew chief gt motorsports.org.

We’d love to hear from you. Hey everybody, crew Chief Eric here. We really hope you enjoyed this episode of Break Fix, and we wanted to remind you that G T M remains a no annual fees organization, and our goal is to continue to bring you quality episodes like this one at no charge. As a loyal listener, please consider subscribing to our Patreon for bonus and behind the scenes content, extra goodies and GTM swag.

[00:26:00] For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can keep our developers, writers, editors, casters, and other volunteers fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, gummy bears, and monster. Consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without fans, supporters, and members like you, none of this would be possible.

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App: |  |  |

Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)