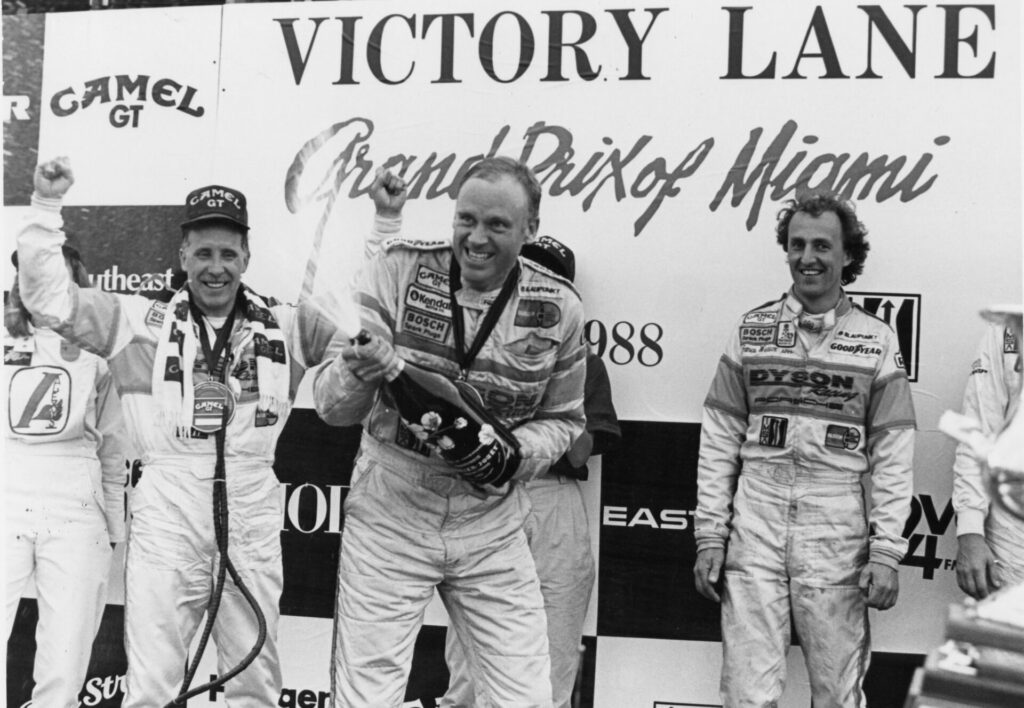

Rob Dyson, who started his racing career in 1974 at Watkins Glen International, In 1981 he won the Sports Car Club of America’s GT2 national championship, and began racing professionally in IMSA GTO and the SCCA Trans-Am in 1982.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

The following year, to support his professional racing efforts, he founded the Dyson Racing Team, which over the next few years grew to be one of America’s premier sports car racing teams. From their base in Poughkeepsie, New York over the course of nearly four decades the team won 19 championships, 72 race victories, started 72 times from the pole and achieved 224 podium finishes. Among the team’s notable accomplishments is a pair of overall victories in America’s premier endurance race, the Rolex 24, at Daytona International Speedway. And In 1986 Rob found himself behind the wheel of a Porsche 956 at the famed Circuit de la Sarthe: Le Mans.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Notes

- Transcript (Evening With A Legend)

- Highlights

- Transcript (Keynote)

- Learn More

Notes

- Your personal attempt at the LeMans 24; you had a successful run starting in 1982 in TransAm, what was your Road to LeMans like?

- Had you raced in Europe before 1986? If so, where, how did that go?

- When you got there, what were your first impressions of Le Mans? (this was still in the last few years before the major track changes.

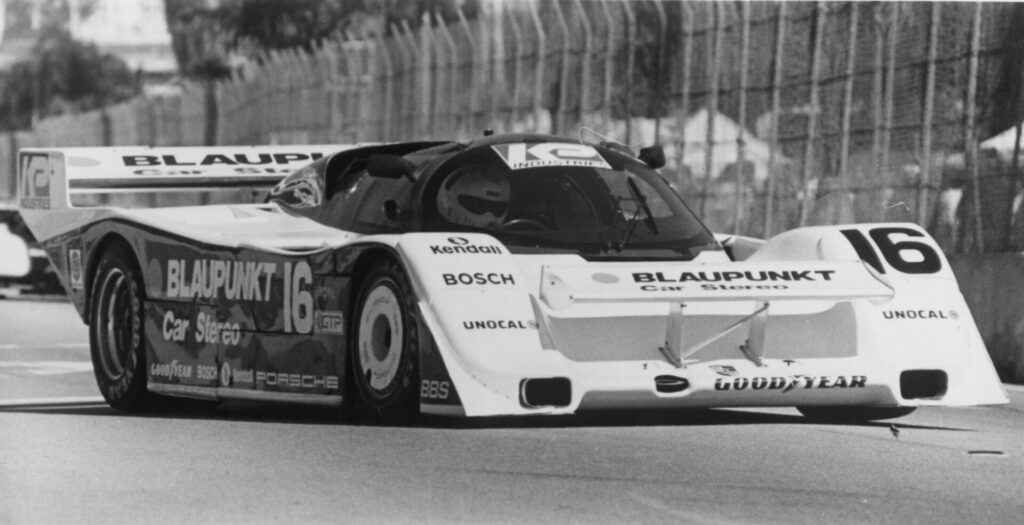

- Let’s talk about the Liqui-Moly Porsche 956 you campaigned in 1986. This was during the overlap period between the 956 (Group C) and Porsche 962. Why the 956? What was it like to Drive?

- What do you feel is the most challenging part of driving at the 24 hours of LeMans?

- This was not the last time “Dyson Racing” would appear at Le Mans – what was it like coming back as a team principal? What has changed with all your return visits to Le Mans?

- We just celebrated the 101st (92nd) Le Mans – Any thoughts on the Porsche 963?

- You’ve seen a lot of change in the last 40+ years; what are some of the best “new” things to have come to LeMans since you started there?

and much, much more!

Transcript (Evening With A Legend)

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Evening with the Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to Legends of the Famous 24 Hours of Le Mans, giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans, with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

Crew Chief Eric: Tonight, we have an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you, sharing in the legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over a hundred years of racing. And as your host, I’m delighted to introduce Rob Dyson. who started his racing career in 1974 at Watkins Glen International. And in 1981, he won the SCCA’s GT2 National Championship and began racing professionally in IMSA GTO [00:01:00] and SCCA Trans Am in 1982.

The following year, to support his professional racing efforts, he founded the Dyson Racing Team, which over the next few years grew to be one of America’s premier sports car racing teams. From their base in Poughkeepsie, New York, over the course of nearly four decades, the team won 19 championships, 72 race victories, started 72 times from the pole and achieved 224 podium finishes.

Among the team’s notable accomplishments is a pair of overall victories in America’s premier endurance race, the Rolex 24 at Daytona International Speedway. But in 1986, Rob found himself behind the wheel of a Porsche 956 at the famed Circuit de la Sarthe. And with that, I’m your host crew chief, Eric, from the motoring podcast network, welcoming everyone to this evening with a legend.

So Rob, welcome to the show.

Rob Dyson: Great to be with you. You know, when you talk about racing, we’re all lucky that we’ve experienced it in some way or form. Whether you’re sitting in the seats and the [00:02:00] grandstands, or whether you’re in the pit crew, or whether you’re driving the cars, I mean, it’s just such a captivating sport.

It’s just remarkable. So glad to be with you.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, for those that don’t know Rob’s origin story, we actually encourage you to check out his keynote address from the 7th Annual Argettsinger Symposium on Motorsports History on the Motoring Podcast Network. But we want to fast forward through your time at Watkins Glen, through the early days of the 80s, To 1986, but take us to 1986.

How did you get to Lamont’s? Was it always a goal? Was it a bucket list thing? What kind of deals had to be made to get you from America over to racing in France?

Rob Dyson: All I can tell you is, is that, uh, you know, relating these stories is kind of got me thinking about it. I was fortunate. I had good support from my wife, from my family.

I consider when I look back on my life, I’m glad of one thing. When I got out of graduate school, I said to my wife, I want to go racing one year. I want to understand what it’s like out there. Which was Chris Economacky’s number [00:03:00] one question that he asked people during his life. What’s it like out there?

I’ve worked on cars all my life, and when I got out of grad school from Cornell, I said, well, we aren’t kids, let’s just do it. I bought a clapped out Datsun 510 because I did some research and Datsun had a lot of speed parts and I figured we’d get something going there and uh, we’d be able to get the parts and handle that and get that done.

So, when I think back on how I would travel to the races in a business suit, I was building a radio business nationally so I was on a plane all the time and I’d get off the plane at Portland or Laguna or something in a business suit. So, in those days everybody traveled in business suits and go to the truck and Get into my stuff and was it fortunate enough to be able to do it and feel pretty good about it and do a pretty good job.

So the thing that’s, uh, it’s interesting is that it wasn’t on my bucket list, but it got to be that I was driving pretty effectively at the nine, six, two. And that’s what those guys were racing. So I figured, well, hell, if I can stay up with [00:04:00] those guys, in fact, beat a lot of them, including some Lamont’s winners, maybe there’s a shot for me.

So that’s what I did. And the thing is that. I went over in 85 merely just to kind of take a look at it. And it was there that I got to know Richard Lloyd, James Weaver. And I got to know one another in 85. James did a race for us in 85. I couldn’t make the race down in Atlanta. So he priced it, the race in 85.

So I met Richard Lloyd and we just struck up a friendship and started talking, but I was interested to see the Le Mans thing and kind of get a handle on it to see what it’s like. And then the next year I talked to Richard and I said, Richard, what can we do? Do you have an opportunity for me? He says, yeah.

And he says, why don’t you plan on doing Silverstone, which generally happened two to three weeks before Le Mans, maybe a month, then you did Le Mans and then Spa. I said, gee, that’d be great, but I don’t think I have the time to do all of them. So why don’t we try to just do Le Mans? So we started talking about it and we worked on it and off we went.

And at the end of the day, [00:05:00] Richard rolled out a, uh, a nine, five, six that he had raced with his guys over in the world championship over in Europe. And that’s what got me in the car. It was merely curiosity. And then. Richard saying, you know, why don’t you hop in and do it? And I felt confident that I could do it.

Crew Chief Eric: So you said you wanted to go over there and check it out and see what it was all about. That first impression, what you imprinted on when you got to Lamar, how different was that than racing in the United States? What was your impression of Lamar when you first got over there?

Rob Dyson: Well, I never raced at Silverstone.

I didn’t go there. I just went to Le Mans, but Richard wanted me to run the Silverstone to get used to driving the car and all that. And that was the old configuration of Silverstone’s changed significantly since. No, I went over to Le Mans and what I was impressed with was that, you know, these were cars from all over the world, very exotic teams, a lot of drivers I’d never even heard of, guys that were really quick too, by the way, and I got to see how the Porsche factory ran their deal, you know, the Jaguar guys, how they ran their deal.[00:06:00]

Because remember, we were running sort of against Holbert, we were running against the Porsche factory in the U. S., and then we were running against Jaguar in the U. S. as well. So it just gave me an appreciation for how the dynamic and what you need to do to get the deal done. But in 85, Richard, his car finished second to Joost, and they probably would have won the race, but they had a false reading of a sensor.

And so they had to back off the car a little bit and they came in second, but they were running up front the whole entire 24 hours. But the thing is, is that when I got to 86, it was just, I had a better feel for not only the people, but I also had a better feel for what it entailed. Cause while I was there, you know, obviously I got a small scooter, borrowed it from Richard and just kind of rode around the circuit before the racing started and kind of get a feel for it.

So I had a chance to kind of look the place over. I said, well, you know, let’s try it. So that’s what we did.

Crew Chief Eric: By doing that sort of, let’s say, hot lap on a Vespa there, did you find any of the [00:07:00] corners suddenly like, Ooh, that’s going to be tricky. That’s going to be tough.

Rob Dyson: It wasn’t a particularly daunting track.

I mean, you know, the corners were the corners. And it was a long track on a lot of roads. And I felt, well, okay, this all looks sort of familiar, you know, when you read the magazines and you see the layouts and all that. I mean, I understood from the year before that the Mulsanne straight’s pretty long and the cars go pretty quick.

And that’s how I just handled it. I said, okay, let’s go.

Crew Chief Eric: Which is interesting because you weren’t a stranger to a car that was capable 200 miles an hour because you were already piloting 962s. I was doing my own research and I had just kind of scratched my head for a second. It’s like 956 in 1986. This is the period where there’s an overlap between the 956 Group C car and the 962s.

So did you feel like you maybe you were taking a step backwards running the 956 or how did it compare running the Liqui Moly 956?

Rob Dyson: Well, fortunately, there wasn’t much difference between the 956 and the 962. [00:08:00] The 956, they just had a slightly shorter wheelbase, water cooled engine, actually not as powerful as our air cooled engine that we were using, but the car, the basic ergonomics, the instrumentation, and everything, it The way the gearbox worked, the way the visibility went, the mirrors and all of that was the same as a 962.

The only fundamental difference was the power plant, which was different. And also the wheelbase was just a little shorter because John Bishop said you’re going to put the driver’s feet behind the centerline of the wheels in the 956. Your driver’s feet were slightly ahead, which when I got in the car for the first time, Price said, remember, this is a 956.

It’s got a shorter wheelbase, so if it looks like you’re going to hit the wall, pull your feet back, which, you know, so I’ll keep that in mind.

Crew Chief Eric: Was that the first time you got to drive a 956? Was that outlap going into your first practice round at Le Mans, or had you had experience with the car prior to that?

Rob Dyson: Nope, that was it.

Crew Chief Eric: Doing a lap at speed [00:09:00] versus doing it on a scooter, did it all come together for you? Did it change your perspective of Le Mans, especially coming down the Mulsanne at over 200 miles an hour and braking zones and learning a new car? What was your takeaway at that moment?

Rob Dyson: Well, one of the things when I first started out, I went around a very slow lap and then I started to pick up the pace on the Mulsanne, which in those days was virtually straight, except for the kink at the end.

It had a slight hill and a slight kink going in the Mulsanne corner. They had these sign boards saying 3, 2, 1, and an arrow saying turn. Well, okay, I absorbed that, but I didn’t absorb it enough to realize that it’s me, so I was going 3, 2, 1, okay, I gotta turn. Well, I realized that the Mulsanne Corner was still another tenth of a mile further.

And I almost wrecked the car. I literally almost wrecked the car. How I saved it, I have no idea, because I was downshifting, getting ready to turn, and all it was was guardrail, and I said, holy shit, wait a minute. That was a quick tutorial to say, look, you gotta master this part of the racetrack.

Crew Chief Eric: One of the questions [00:10:00] that we got from the crowd, and Terry asked, how does the strategy differ?

We’re in approaching a six, 24 hour race. And obviously you came to Lamar with Daytona already on your resume, but the lap at Lamar is so much longer. So what type of strategy did you have to implement as a driver to keep your cadence throughout your entire stint? A

Rob Dyson: couple of things. One was, is that Reinhold Joost came up to me and I asked him, I said, Hey, what kind of hints about Lamar’s?

He says, do not touch the curves. The various curves on the corners don’t touch the curves. Brian Redman said that when you go down the Mulsan, go down as much as you can, or as long as you can, in the center. Especially when you come up over the hill, because you don’t know what’s going to be there, and you want to make sure you can go either left or right if there’s something in the middle.

Funny thing about the Mulsan Strait is it gives you a lot of time to think. And that was one thing that Derek Bell said. He says, don’t let your imagination get away from you. You got 60 seconds with your [00:11:00] foot to the floor. Just don’t think about it. And that took me a little while to think about it, and especially during the race when it was starting to rain.

Crew Chief Eric: Stuart asks, you mentioned Bell, Redmond, Yost, all racing Porsches for various teams. Of all the drivers with whom you spoke, who gave you what you would consider the most comprehensive, honest, or best advice?

Rob Dyson: You lie. Fourth, that was when IMSA was racing at Lime Rock. Everybody that was going to do Le Mans had to get down to Kennedy Airport to fly out on Sunday night to get to France and get down to the racetrack for the Tuesday inspection.

And you had to be there. You had to sign in. Fortunately, we had a travel agent, Marion Champlain, who started with us and started a huge catering operation as he’s since retired from racing. Marion was a travel agent. She set up all the logistics. She hired small planes to fly us down to Kennedy Airport so that we could make the Air France flight.

And there must have been about 15 of us that were doing Le Mans. Goes to show how times have changed. [00:12:00] Landed. Plane’s taxied up to the jet. We got off and went up the stairs to get on the plane. When I was flying over, Brian Redman came over to me and I wish I’d kept it. He handed me a eight and a half by 11 pad with his advice as to how to race Le Mans.

I devoured that. In fact, I read it. I gave it to Cobb. Cobb may have it. He was the guy that gave all the detail on how the pit straight is, the kind of gearing you’ll use going underneath the Dunlop Bridge, going down through the esses, how to handle the Mulsanne straight. He was the one that wrote, go down there in the middle as much as you can, especially over the brow by the kink.

The Indianapolis, you’ve got to be very careful there, the road leading up to Indianapolis is crowned, and it still is as a matter of fact, so you’ve got to be careful that you’re not going to unbalance the car, pick a side and go down that side, and so you’ve got to kind of stay with it, and that was the most edifying of all of it, and he was, was [00:13:00] then, and is even now, a very, very, very close friend.

The other thing is that the car was really set up pretty well, we ran the long tail. The long tail is a streamlined tail. Racing on IMSA, we had a high tail, more of a sprint format. The other thing is because we were running this water cooled engine, which was very benign, a 2. 8 liter engine that was almost silent, it was very quiet, wonderful balance.

It wasn’t quite as loud or noisy in the cockpit because it didn’t have the blower fan like the 962 did. That was a significant difference in kind of the way the car felt. It was just quieter. You were doing all these very fast speeds, but somehow it was just quieter and a little bit more I won’t say relaxing, but it was a little more calming than having the air cooled engine, which sounded loud from the start in the cockpit.

The fortunate thing is, our relationship with Goodyear was pretty deep, and so we were running Goodyear tires. And so we were running Goodyear tires that we knew how they worked, and we [00:14:00] knew how they ran. We had several of the same tire engineers that we had with IMSA. So you had that advantage, but the strategy was, you know, just go until the red light comes on, and then come to the pitch.

Drive as fast and as comfortably as you can. You know, the stopwatch tells you whether you’re doing anything or not. You work up to it. We did not have radios in those days. Nobody did. Nobody had radios. People were experimenting with them, but the communications laws and all that stuff in France said you can’t use radio, where we were just starting to use them in the U.

S.

Crew Chief Eric: So no radios. New track, new car, and new teammates. So talk about the relationship with the other guys driving the 956.

Rob Dyson: The guy that was the European, the Liqui Moly sponsored driver, was Mauro Baldi, who we have known from being over in the States. He ran in the States as well. Very affable, very good guy.

And then Price Cobb, of course, who’s probably my oldest friend in racing. So Price and I went over there as kind of a package. You know, you got to understand, I’m a business guy. I didn’t do [00:15:00] this for a living. And I didn’t do all the races from 1981 on. I never did a full season of racing or whatever class I was racing.

Then we met with Morrow and he drove us around the racetrack and when it was a road, when it’s open and you can just drive around and take a look at it, he explained a lot of intricacies and the kind of the tricks of the trade, he was very, very forgiving of our ignorance. And so he was a great teammate in that respect.

Crew Chief Eric: Being a businessman and time being part of the constraints of your ability to complete a season and things like that, were you considered just part of the team, or were you looked at as, let’s say what we would call today the bronze driver, or the gentleman driver, or how were you positioned in that hierarchy?

Rob Dyson: Well, Price and I, of course, were raised together. So it wasn’t like, who is this guy? So Price and I, we’d done pretty well on a couple races. One out of Riverside and, you know, we were, we were a unit. There was no problem there. Baldy, I think, respected us. I don’t know whether he ran at Riverside when we ran there.

But, you know, he, he knew us as being serious [00:16:00] drivers. In fact, what I did for a living was kind of irrelevant. I didn’t feel out of place or, uh, I didn’t have any sense that, You know, I was behind the eight ball. It was just, Hey, I got a job to do and let’s go. That was the great thing that I had about racing is that it was so different than what I do day to day.

So I didn’t feel unequal to anybody.

Crew Chief Eric: When you come in from your stint and you have an opportunity to download with one of the other drivers that isn’t running, what would you guys talk about? What kind of information were you sharing? Cause obviously you had this. Two hours or however long you were out there where you had no communication, what kind of information were you downloading back to the team and to the drivers?

Rob Dyson: In those days, that was the state of the art. So in other words, you weren’t coming from any flaw or anything that, you know, the other teams didn’t have anything on us. Even the Porsche guys, they were suffering from the same, couldn’t download all the information on the way the car was performing. But I think the main thing that we talked about was just, How you handled the mechanics of the car, shifting, brake [00:17:00] points, feel of the car, that was the biggest thing.

Crew Chief Eric: Marky Smith Haas writes, given the brakes had such a long time to cool off during the car’s trip down the Molson Strait, and then the hard braking heat up for the Molson corner, did you need to lightly drag your left foot on the brake before hard braking to warm them up? Or did you experience cracked rotors as a result of the extreme heating and cooling?

Rob Dyson: No, but during the race in those days, you changed brakes. Definitely changed pads. Nowadays, they don’t even do that. Or they rarely do it. Carbon brakes and carbon pads and the technology they brought to bear on it. And we were present when we were doing that early carbon brake stuff with prototypes we were running.

We were using steel brakes. That was the way you had to do it. And this is true also at Daytona in those days. When you came down the straightaway, when you crossed the stripe, you kind of rolled your left foot over the brake just to touch it a little while you’re flat out, just to get them a little bit warmed up.

And you had to do that at the Mulsanne. The rest of the time, you could pretty much brake normally. The thing that we had in our [00:18:00] 956s, we were the slowest of all the Porsches on the straightaway. We were the quickest of all the Porsches in the corner, because we did not run a Le Mans undertrack. We ran a sprint racing undertrack.

So while we were slower down the straight, we had better traction and better handling through the corners. We were running times that were equal to the guys that were running far ahead of us. And it was one of the reasons why we were able to make up so much time when we slipped down on these different maladies we had.

But the braking, that’s a great question, but braking, even braking has changed now. There’s no degradation in the braking now because they’ve made the technology so good.

Crew Chief Eric: Margi also writes, I was advised to drag the brake when I drove an 84 in the Group B 930 and competitors were having to pit to change their brake rotors all the time.

Rob Dyson: Yeah, it was a common thing. We did it at Daytona. That was one of the things that we spent a lot of time developing the tools to enable us to squeeze the pads back to get new pads on. And have it help you if you had to replace the actual [00:19:00] discs itself, because that took a lot longer. Nowadays, they have click in, it’s literally a quick disconnect, they can disconnect the calipers, pop the whole setup out, and then put the new setup on.

I saw that, in fact, I think I saw that at Watkins Glen, a Porsche did that just this past weekend.

Crew Chief Eric: So you mentioned the rain, and we’ve talked many times before about the variable weather conditions at lama. It could be sunny on one side and a downpour on the other. It’s just so big and so spread out. It just happens to have its own interesting microclimate.

Your year 86. It rained quite a bit this year at the 101st anniversary of Le Mans in 2024. It rained quite a bit as well, but they didn’t have safety cars holding up the show in 1986. So what was driving in the rain like at Le Mans? What did it teach you about your driving? Was there anything you took away from it?

Rob Dyson: Well, it wasn’t much because that year we had a lot of weather changes. It didn’t rain hard, but it rained enough. So that was whatever you learned, you [00:20:00] couldn’t impart on anybody. Because, you know, you had to go on. Experiences herself pretty straightforward. I mean it was it was gonna be a long race and you just got to make sure you preserve the car Don’t wreck anything.

Crew Chief Eric: That’s a common theme amongst a lot of the drivers We spoke to is this idea this concept of mechanical sympathy and not every driver is maybe as sympathetic as another one But the goal is to maintain that consistent lap time from one driver to the next to the next and the car has to survive Winners bring it home at the end of the day if it breaks somewhere in between that’s a failure

Rob Dyson: Ironically, that is the first fundamental difference between endurance racing now and endurance racing then.

Nowadays, the cars don’t break. If you take a look at all the cars that started the Daytona race, Sebring, Le Mans, any of the long distance makes races, Silverstone, the six hours of Watkins Glen, Petit Le Mans, Cars don’t break anymore, and that’s a result of a whole lot of things, one of which is a lot of computer driven and computer measured fuel, incredibly [00:21:00] well built products that are put in the car, the cars are built better now.

The other thing is, is that the gear shifting is all done by paddle shift, and the paddle shift is all computer controlled, which means that if you’re going along the Mulsanne Strait, nowadays they’re going about 210 maybe, the Jaguars were going 240. When we were racing, we were going about 220 to 222.

But the thing that is different about it now is that they have the ability to not miss a shift. They don’t miss a shift anymore because the computer won’t let, it’s a wheel speed thing, the wheel speed catches up to the speed of the car and that lets the gear shift go down. All of that is completely different.

In our deal, it was a five speed, and off you went. Fortunately with the Porsches, it was one of the great characteristics of it was, is that they were synchro gearboxes. The negative of it was, particularly in street courses and incident, you couldn’t quite get the shift quick enough. Whereas the guys with straight cut gears like Hewland and the Jaguars and a lot of the [00:22:00] other guys, they could just jam the gears a lot quicker.

But in our case, we had to make sure with all the dog rings and all the things to make a synchronized gearbox synchronized, you had to be careful with that. But that is the fundamental difference between racing now and racing then. Ricky

Crew Chief Eric: So I’m glad you brought that up. Your thoughts on the 963 in comparison to the 962 and the 956.

Transcribed by https: otter. ai

Rob Dyson: Well, it’s typical Porsche. I mean, they, you know, they take it very, very seriously. I think having it under the, uh, aegis of Roger Penske also helps. They spent the budget on the car. The cars are clearly good. They’re clearly reliable, but they worked an awful lot on that.

Those cars are incredibly complex. They have hydraulic front brakes and electric rear brakes. That all has to be coordinated. You know, in our deal, they were mechanical, fluid pushed braking all around. Now it’s fly by wire. It’s a big factor. And the hybrid is another thing. Plus, the cars are a lot heavier.

Crew Chief Eric: At the end of your personal run in 1986, walk [00:23:00] away from the event, from the car, what were your thoughts? How had your impression of Le Mans changed after being behind the wheel, going through all the weather conditions, all the things that you experienced while you were there?

Rob Dyson: Well, you know, it’s kind of funny.

The thing that happened to us was Mauro Baldi got sick. He got sick after his first, uh, he was sick actually when we met him and then during the night before the race he was in really bad shape. He got in the car and ran the first stint and from then on we didn’t see him until the end. He didn’t drive with us at all.

He did no driving after his first hour and a half stint in the car. So it was just Price and I, kind of back to the old days. You know, it was one of those things where, uh, where we were just able to just run the car, just he and I. The most important thing about LeMans was we survived it. Joe Gartner was a real up and coming talent.

He was driving a Kramer car and the transmission locked up. He hit the armco barrier, car cut in half, died of his injuries there. But I think the biggest thing was is that I came out [00:24:00] of it, we finished, we were running as high as fifth, we finished ninth. We were as low as 17th, we had some car problems that were inexcusable, never should have happened.

Had we not had the car problems, I think we could have been up in the, easily in the top five. We had a very fast car. The thing that was significant about it was that after that, there was no straightaway that was long. Any other racetrack I raced on, the straightaway was never as long. You were never on the foot to the floor for as long as you were.

And had the time to think about it as you did it going down to Mulsanne Street. The other thing is, I was kind of afraid of the dark. I’ve always been a little bit afraid of the dark. Well, when I finished Le Mans, I was not afraid of the dark anymore. Running in the rain in the middle of the night, which didn’t last very long, but running in, running in the rain in the middle of the night, 220 miles an hour, cars darting all over the place because the adhesion was poor in those rain tires.

You know, that was the other thing that kind of changed. I could be in total darkness and not have to have to worry about it.

Crew Chief Eric: Was it [00:25:00] something you wanted to do again?

Rob Dyson: Well, I’ll tell you why I only did it once. I only did it once because first, now it’s a real time sink. You’ve got to be there for a period of time.

We got off the plane on Monday, uh, Monday morning and we were at the track on Tuesday and we read, we did inspection on all that and ran Wednesday. Wednesday night, Thursday qualifying, Friday had off, and then Saturday was the race, and Sunday, you know, we headed off to the airport. Now it’s a lot longer, a lot more elaborate timing wise.

Had I not finished, had our car not finished, we had wheel bearing problems, I had a, we had a shock absorber go, all had to be replaced, I had a lower control link go on me and the, and the kink, at about 200 miles an hour, popped the right rear wheel. Kind of on its edge, slowed up, came in, they fixed it, and off I went, got back into it, I couldn’t believe it, I actually did it in retrospect.

But anyway, so, if I had not finished the race, and not had the experience of driving around that track at the [00:26:00] end of the race with the corner workers coming back onto the track surface, waving all of their flags, their congratulations for having survived it, And in those days, remember one guy didn’t and they had a, another team, a GT team had a, a pit fire and they had some people really seriously injured there.

So, you know, it was kind of an experience that I’m glad I did and I don’t think I could have duplicated it, doing it again. I just felt that, I hung it out there. I had done it, did a great job, my times were comparable to all of the top guys. I felt very confident driving the car at the tail end, I finished the race.

I just think that the experience was hard to beat a second time, so I decided not to do it. I had plenty of offers from other people, other teams, to do the race. Jaguar called me, uh, Tony Dow was running the Jaguar team in the U. S. said we’d like to come and test and maybe do Le Mans with us. And I said, Tony, no, I just, I won’t have the time to do them.

You know, that would have been a first rate team. Knowing those guys and racing [00:27:00] against them, they were good. They knew what they were doing and had great equipment. I just felt that it was just good once and, uh, let’s not push your luck. That’s really what it was.

Crew Chief Eric: So it sounds like Le Mans made you a better driver.

So you took that with you back to racing here in the States and other places then. Oh, yeah. So 1986, that was your time behind the wheel at Le Mans, but it was not your last time at Le Mans. So let’s talk about the years following that and especially coming back as the team principal for Dyson Racing and also supporting your son Chris’s three attempts at Le Mans in 2004, So what was that like coming back after all the changes?

From your time behind the wheel, because the Molson had changed, the pits had changed, all the new buildings that were put in place. What was it like returning to Le Mans as a team principal?

Rob Dyson: Well, it was kind of interesting. Chris signed on with Jan Lammerstein in prototype. Jan had driven for us. And a couple of races.

And when I got there looking around, the place was [00:28:00] substantially changed. I mean, the garages in 86 were the same garages that were there probably since the late 50s. And they looked, it reminded me of Sebring before Don Panos Same kind of thing. Plaster was falling off the ceiling and the bathrooms were, I think, a mixed company.

I wouldn’t like to describe them, but anyway, kind of a mess. But the other thing that changed, of course, was the fact that the teams had radios. They had more electronics. They had the setups in the garage. They had setups out on the pit wall to monitor how the cars were doing. And taking a brief again on a, on a scooter that Ann Lambert’s had, I talked to the organizers and they let me ride around in a, um, more of a motorcycle so then they’d get it done quicker and ran around the course and it was substantially different.

They got rid of the S’s, the, uh, Dunlop Bridge is different. It’s slower. They put a chicane there at the end of it. In fact, I think one of the reasons why the Toyota lost in second place was because they spun out there. But the Mulsanne corner was in essence the same. [00:29:00] Down into Indianapolis, it was the same, and the Porsche cars were the same.

But the runoff area was a little bit better. Still not great. I still think it’s probably one of the most dangerous racetracks on the planet. Onco barriers have long since been discredited as a safety barrier. But that’s what they line most of the track with. Frankly, it’s because most of them will sound straight as a road, but the chicanes were the thing that were just staggering how slow it made the cars go.

And yet, the cars at the end of it qualifying faster than we ever did. Shows you how technology and cornering speeds and braking have changed. I found it different, but it, you know, it was good to be over there to see Chris run. When I was there, I met so many of the people that I actually raced against 20 years before.

Different people from all walks of life, but the thing is, is that the spirit of the place and the daunting task it is to run that race and to win it still remained.

Crew Chief Eric: You talked about how Brian Redmond gave you all this advice, and you know, you still wish you had a handwritten note, wherever that ended up, and [00:30:00] that was sage advice at the time.

But you also said how much the track had changed, especially when you lead into 1989 and 90 and so on, where it really started to take the shape that it has today. Being very involved in your son, Chris’s racing career as part of Dyson Racing and all that, it was probably very difficult to relay any advice to Chris because the track was so different.

So what did you guys talk about? Did you find common ground? Was there some sort of shared experience there between Le Mans of the past and Le Mans of today?

Rob Dyson: Some. I told Chris that he’ll feel formal pressure. There are a lot of races. But I think there are probably five races, you know, that are real races.

Le Mans is one of them. Indy 500 is one of them. Probably the uh, Grand Prix of Monte Carlo is one of them. Bathurst is one of them. The Daytona 500 is one of them. But then, you know, you get down to them and all the rest of them are kind of just car races. I told him that when he goes over there, it’s going to be a different thing.

Because when he went over there in 89, they hadn’t done all the chicane work. They [00:31:00] had changed a little bit of the, actually came close to running the same course that I ran on. But they did add a chicane going onto the straightaway. They since moved it further down, so kind of a Mickey Mouse chicane. But the big thing was, is that I just said to him, you’re going to feel a little more pressure on this one.

But Chris was pretty experienced by the time he did it. He had run a lot of races with us and did pretty well. So he kind of knew the score. But I think other than saying that, you know, this is it. If you’re talking sports cars, this is the Indy 500 of sports cars. This is it. To do well at it and to finish it is really important.

And that’s the one thing I told him to get with his guys. And so then everybody knows they’re not a hero, that everybody has to handle with a car in good shape. Between one driver and the next, because if you got it, some guy, you know, wrecked third gear, pretty soon second or fourth is going to go. And in those days, he was shifting.

It wasn’t paddle shift in those days.

Crew Chief Eric: One of the questions that comes up from the crowd quite a bit is if you could pick any one of the [00:32:00] current 2023 or 2024 season Le Mans cars from any of the classes, and let’s say you could get behind the wheel tomorrow and turn another lap. At Le Mans, what would you choose?

Would it be the 963, the Ferrari, one of the LMP2 cars, something else?

Rob Dyson: Well, clearly, I think I can probably get into the Porsche probably easier because I know who I am and I know my record with working with them. I’ll tell you, the Ferraris are pretty damn impressive. The Toyota cars are superb as well.

Not taking anything away from the Porsche guys. But those Ferrari guys, they were really hooked up. And what was interesting about all those guys that were running the two lead Ferrari cars, and then the non works car, they were all GT trained. They were not open wheel guys that came down to race. They were all guys that started factory programs in GT cars.

That’s what so impressed me about the fact that these guys, they were flying. I mean, all of those guys were really running hard. Again, they were running hard because they could. They were running hard because they made it possible to be able to run [00:33:00] a car consistently harder all the time than it used to be, for all of the reasons I mentioned earlier.

That Ferrari, clearly, it’s pretty cool. It’s a, I think it’s a, you know, one of the striking cars racing out there. It’d be interesting to see what one of those is like, but clearly, you know, you know, that was then, this is now, and you know, 50 years later, we’re still doing it. While I’m not doing it personally, driving that is, which was a lot of fun.

I enjoyed all of them. To be a part of it still, through Chris, and now through my grandsons, they’re both starting to do some racing. Go karts for John at this point. So eight years old, it’s kind of like, uh, you know, it’s like Ted Williams. He’d like to think he could hit a home run against a major league pitching at the age of 75 or 80.

But the reality of it is by the time you’re swinging, the ball’s already gone into the catcher’s net,

Crew Chief Eric: which actually leads into a great sort of closing question, Rob, let’s just say somebody walked up to you, maybe at the Glen or one of the other tracks that, you know, you’re still frequenting. And says, [00:34:00] Hey, I heard you drove at Lamont, but I don’t know anything about it.

You know, I wanna learn more about the race. Why should I either go all the way to France to see it, or why should I tune in to watch it on tv? What would you say to those folks?

Rob Dyson: Well, I think because it’s lamonts, I mean, uh, after the Indy 500, I think it’s one of the longest, one of the oldest continuously run races in the world.

I mean, there’s a tradition, there’s a history. I mean, the Bentley boys started in, you know, the mid to late 20s. I mean, they were running cars of Le Mans in their teens. It’s the tradition of them. The other thing, I think, it’s all the resources that everybody puts into it. Porsche made their name and made their reputation.

Running and winning Lamont’s, they are masters of having done that well. And it was a part of their corporate objective every year that we are going to win Lamont’s and that’s part of it. The tradition, the competition, everybody brings their best stuff. Before

Crew Chief Eric: we close out, I would [00:35:00] love to turn the microphone over to ACO USA President David Lowe

David Lowe: for some closing thoughts.

Well, again, Bob, I certainly want to thank you on behalf of all the members. We certainly appreciate your time and look forward to you attending one of our live events as a legend.

Rob Dyson: That’d be great. I’d be honored to do it. You know, it was long ago, but, uh, when you start thinking about it, all I can tell you is, is that I’m really honored to have been able to do the racing that I was able to do.

It’s an honor to impart what I’ve learned to people, and I’m really honored that you asked me, Eric. I really appreciate it.

Crew Chief Eric: And thank you, Rob. And I do want to turn the microphone over to Bob Barr, press president of the Society of Automotive Historians and a member of the International Motor Racing Research Center that helped co sponsor this evening with the legend.

So Bob.

Bob Barr: 40 years ago, I was a brake and suspension mechanic and lowly G production SCCA, which doesn’t exist anymore. So Rob, I found a lot of your talk really fascinating about the brakes. Just a thank you to Rob. Dave and [00:36:00] Eric for putting this on. This is a real treat. Thank you all.

Crew Chief Eric: During his 21 seasons as a professional racing driver, Rob Dyson drove in 92 races, scoring four overall race wins, including the 1997 Rolex 24 at Daytona, and a total of 18 podium finishes.

Rob continued to compete episodically in professional racing through 2007, and today remains active, driving his collection of vintage Indy cars in a variety of demonstration events. He was named chairman of the board of the directors at the Indianapolis motor speedway museum in 2021, following a decade as a member of the board.

And he is guiding the institution through its 89 million transformation and renovation and charts its future path as a repository of history and related artifacts of America’s oldest active and most storied racing facility. Rob is still involved in the Dyson racing team. And supporting his son’s efforts and his grandsons.

And so look forward to more things coming from Rob in the future. And on behalf of everyone here and [00:37:00] those listening at home, thank you for sharing your story with us. And we hope you enjoyed this presentation and look forward to more Evening with the Legend throughout the season. So Rob, thank you again for coming on and we appreciate you sharing your time and your stories.

Rob Dyson: Thanks everybody. It was an honor to be here.

Crew Chief Eric: This episode has been brought to you by the Automobile Club of the West and the ACO USA. From the awe inspiring speed demons that have graced the track to the courageous drivers who have pushed the limits of endurance, the 24 Hours Le Mans is an automotive spectacle like no other. For over a century, the 24 Hours Le Mans has urged manufacturers to innovate for the benefit of future motorists.

And it’s a celebration of the relentless pursuit of speed and excellence in the world of motorsports. To learn more about or to become a member of the ACO USA, look no further than www. lemans. org, click on English in [00:38:00] the upper right corner, and then click on the ACO members tab for club offers. Once you’ve become a member you can follow all the action on the Facebook group ACOUSAMEMBERSCLUB and become part of the legend with future Evening with the Legend meetups.

This episode has been brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports as part of our Motoring Podcast Network. For more episodes like this, tune in each week for more exciting and educational content from organizations like The Exotic Car Marketplace, The Motoring Historian, Brake Fix, and many others. If you’d like to support Grand Touring Motorsports and the Motoring Podcast Network, sign up for one of our many sponsorship tiers at www.

patreon. com forward slash GT Motorsports. Please note that the content, opinions, and materials presented and expressed in this episode are those of its creator, and this episode has been published with their consent. If you have any [00:39:00] inquiries about this program, please contact the creators of this episode via email or social media as mentioned in the

episode.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Introduction to the Legend of Le Mans

- 00:43 Meet Rob Dyson: Racing Career Highlights

- 02:17 Journey to Le Mans: The 1986 Experience

- 05:17 First Impressions and Challenges at Le Mans

- 09:59 Racing Strategies and Insights

- 20:34 Endurance Racing: Then and Now

- 22:55 Reflections on Le Mans and Future Involvement

- 27:16 Returning to Le Mans as a Team Principal

- 34:57 Closing Thoughts and Acknowledgements

Transcript (Keynote)

[00:00:00] Brake Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family.

A Driver’s Reflections on Watkins Glen at 75 by Rob Dyson. Rob Dyson is a New York based businessman and retired professional racing driver with a long association with Watkins Glen International and the International Motor Racing Research Center. Following completion of his licensing school at Watkins Glen in 1974, Dyson began competing in amateur SCCA competition.

In 1981, he won the Sports Car Club of America’s GT2 National Championship. Dyson began racing professionally in IMSA GTO and the SCCA Trans Am Series in 1982. The following year, to support his professional racing efforts, Dyson founded the Dyson Racing Team, which over the next few years grew to be one of America’s premier sports car racing teams.

From its base in Poughkeepsie, New York, over [00:01:00] the course of nearly four decades, the team has won 19 championships, 72 race victories, and started 72 times from the pole and achieved 224 podium finishes. Among the team’s notable accomplishments is a pair of overall victories in America’s premier endurance race, the Rolex 24, at Daytona International Speedway.

The team fielded cars during the heyday of IMSA Camel GT, winning the first time out with a Porsche 962 at Lime Rock Park. Under Dyson’s leadership, the team went on to successfully field entries in IndyCar, the World Sports Car Championship, the United States Road Racing Championship, and the American Le Mans Series, where the team scored two championships, the Rolex Sports Car Series, and the Pirelli World Challenge, where the team scored Bentley’s first ever North American race victory.

During his 21 seasons as a professional racing driver, Dyson drove 92 races, scoring four overall race wins, including the 1997 Rolex 24 at Daytona, and a total of 18 podium finishes. Dyson continued to compete episodically in professional racing through [00:02:00] 2007, and today remains active driving his collection of vintage IndyCars in a variety of demonstration events.

Dyson’s personal historic IndyCar collection ranges from a 1913 Isotta Freschini Tipo IM to Johnny Rutherford’s 1978 Budweiser McLaren M24B, and includes the 1961 Kimberly Cooper Climax, the first successful rear engine car to compete in the Indy 500. Named chairman of the board of directors of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum in 2021, following a decade as a member of the board, Dyson is guiding the institution through its 89 million dollar transformation and renovation as it charts its future path as the repository of the history and related artifacts of America’s oldest active and most storied racing facility.

In 2011, Dyson donated to the IMRRC the historic archives of National Speed Sport News, America’s premier motorsports news publication since the late 1930s. Dyson is chairman and chief executive officer of the Dyson Kisner Moran Corporation, a privately owned international holding company. I am [00:03:00] thrilled to be able to introduce you all to Rob Dyson.

Rob has had a long association with Watkins International as well as the Research Center. Couple of highlights of Rob’s career, received his competition license in 1974, 1981 he won the SCCA GT2 National Championship. 1982, Rob participated in his first professional race, MCGTO and SACA Trans Am, and in 1983, Dyson Racing was formed.

19 championships, 72 victories, and two Rolex 24 victories to date. Rob himself raced 21 seasons, 92 races, and 18 podium finishes in that time span. Rob is passionate about history, currently serves as chairman of the board of the International Motor Speedway Museum, where he oversees the museum’s renovation, which is currently in the throes now towards an 89 million campaign.

Last but not least, in 2011, Rob saw to it that the research center received a donation of the National Speed Sport News Archives, which is a collection that we use almost daily at the research center. So [00:04:00] without further ado, let me introduce you to Rob Dyson. Well, hi everybody. Thank you, Mark. I appreciate the introduction.

One of the things that when I was asked to speak about my personal experiences of Watkins Glen, it’s hard not to be a little bit emotional about it. You know, it really comes in four stages. My first stage here was as a race fan. I think that’s the way everybody starts, some way or another, you start as a race Millbrook, New York in 1963.

In the summer, it was sports car racing. And every year, it was an odd year if I didn’t come up here at least twice. It was summer at Watkins Glen was a norm of some sort of racing, sometimes twice. Can Am, sports cars, any kind of event that was taking place in the summer. Or alternatively, either freezing or getting sunburned in October for the F1 race.

Many of you probably attended the F1 races. My first one was in 1965. And the one thing that so [00:05:00] disturbed me was, it took an awful lot of effort to get into the pits. Fortunately, if you looked at the color coding of the pits, Pit passes in those days and brought one of those packets that you get in the school supply store, multi colored, you get the rest of the idea.

Just to show you how important Watkins Glen and being here and coming to events at Watkins Glen as a race fan. My wife and I were married on August 28th, 1971. In October of 1971, she joined me up here. Fortunately, we were able to get passes, and it didn’t rain that year. But she really enjoyed it, but I’ll talk about her in a few minutes.

So here you go, it started as being a race fan. When I was in graduate school at Cornell starting in 1972, cut classes to come over here for the U. S. Grand Prix because it was so close by. I mean, Ithaca is what, about 45 minutes to an hour away, right? I came over the hill, came here when they were unloading the trucks.

[00:06:00] I said, I’ll get here on Sunday or Monday just to see what’s going on. I helped them unload the trucks. So I got a pass that enabled me to come and I came every single day, including race day. But with the pass, I was able to get around. That was in 72 and 73. I spent the entire week here. And that was in the days when the cars were brought in on a car hauler.

Crews were smaller and they rolled the cars into the, then the Kendal Center. And it was fairly primitive, but it was Formula One. And it was amazing when you think back on it, how it’s all evolved. Now you have minimal crews. I would be surprised they don’t have 200 people at the race per car. In addition to that, I will also admit that I would come over here in my BMW, During graduate school, periodically, and drive this racetrack.

There were very few barriers, and frankly, there was a county road that went right through the racetrack. You could come up to the track, get in. I wouldn’t drive for high speeds, but I would drive the racetrack. For maybe half an hour, just driving down into the boot, coming [00:07:00] up out of the boot, driving around one of the barricades.

that were minimal, not even covering the whole width of the racetrack. So you have to understand that it was Rob Dyson, the race fan, that first got acquainted with this wonderful facility at a very early age. This was before the boot was built, before the pits were built, before even the access or anything remotely approaching a media center was ever built.

Then we go to stage two. Descending into the depths. Now the depths means, I started to race myself. I came over here to start researching. I came over in October of 1973. I said to my wife, I want to do it for one year because I’ve been working on cars all my life. Going to car races, I want to see what it’s like to be out there.

What’s it like out there? The great question that Chris Akonemaki used to always ask drivers. What’s it like out there? I wanted to experience it myself. So I started with a Datsun 510. It was crewed by me and my wife. My second driver school was here. That was when I got my regional [00:08:00] license. My first one was at Thompson in Connecticut and then came up here.

And that gave me a regional license. And then I could go racing. Numerous races in regional racing. We were twice a year up here at the national level. It was either the Finger Lakes region, the New York region, or the New England region that was sanctioning it. And all of a sudden, here I was racing on a track that I was truly finding out what it’s like out there.

And I really, really liked it. It was the ultimate ability to be able to get out there and do what I’d always thought would be pretty cool to do. But I wanted to experience it and I was able to do that. And in 1981 I won the GT two National Championship and in 1981 I won the championship. And in 82 I started doing more club racing.

But to qualify for the runoffs, I only needed to do six races. ’cause I was automatically qualified to come back. I don’t know what the rule is now, but that was the rule then. But in 1982, I decided that maybe [00:09:00] I should step up. And a good friend of mine, Bob Aiken, a dear friend, said, Rob, it’s time to get out of club racing.

So that was stage three. You see how I’m descending into the depths or rising further up the pyramid, I guess? And I went from SCCA amateur racing to SCCA and IMSA. First in 83 and 84 in a GTO slash Trans Am Pontiac Firebird, which was probably the lousiest car I’d ever driven. But by then I had a small crew of guys, there were five of us, and we learned a lot from that.

And what I learned was how good our guys were, and how we should also move up to take the next step to get into prototypes. It was there that I had a very interesting conversation with Bob Aiken, because I related it to Bob. I said, Bob, I want to move up. He said, you should. He said that because we had come third in the 500 miler at Elkhart, I never did a lot of races in the Pontiac.

And actually, after 1981, I never did a full season of racing in any form of [00:10:00] any racing that Dyson Racing did. I said, look, I’m going to go over to England and see the guys that march, and he shakes his finger just like this. Nobody collects marches. He said, the big thing you’ve got to do is get into a car that you know is going to work.

I said, look, nobody can get the 962s. He says, let me call Hobart. You know Hobart. Why don’t you call him? So I called Al, and I said, Al, I want to get a 962. He said, yeah, you can call me. He says, let me see what I can do. And shortly thereafter, we worked a transaction with Bruce Levin, who was a Bayside Disposal entrepreneur, who later became a very dear friend, who I shared several races with.

We were able to get the 962, we picked it up in March, and raced it at Lime Rock, and we won our first race at Lime Rock. The thing that was interesting is one of my crew guys said, why don’t we retire undefeated? We didn’t, of course. So we started racing real cars, like Hovert says, you want to get into real racing.

Here we were running the Porsches. To come up here to Watkins Glen at the sharp end of the entire field, to qualify with all of these great professional drivers and to [00:11:00] go out and run with them, going up the back straight that I had done so many times from my BMW to my B sedan to my Trans Am car, but then to do it in a 962 Porsche.

It was an experience that, other than doing Le Mans, was kind of breathtaking, actually. Then there were a couple other professional races that I did here that was not in the 962, that was done in the Burger King 24 Hours. That was one of the greatest events I’ve ever participated in. Burger King was part of the Firehawk Challenge, which was a showroom stock class.

I was driving with Bob Aiken, and depending on what showroom stock was, depending on how the manufacturer kind of said what was showroom stock and what wasn’t, The advantage that we had, we had better fuel economy and better wear on our tires. But those Burger King races had 70 or 80 cars running here at night.

And even if you have 70 or 80 cars running here at night, Watkins Glen in the middle of the night is a very dark place to race. And then we started running other [00:12:00] prototypes as I started getting less involved in the cars and my son, Chris, his first professional race was up here. We had come up here the week before the IMSA race with the Rileys to do Goodyear tire testing.

And Chris came up and he had a spec racer Ford and we let him run when we weren’t running, when we were adjusting the car, changing something. And I said, why don’t we just put Chris in the car and see how he would do. And in six laps, he would have qualified sixth in the grid the year before. So I said to the organizers when weekend started, I said, hey, I want to add my son.

He’s got a SCCA competition license. Can we give him an IMSA license? He’s got all the medical. And Chris got in and drove his first pro race in a Raleigh. He took my time away from me in the six hour. Unfortunately, we had an electrical problem with the car, but Chris did a terrific job and that led to him barely a year later, he and James, we were winning the six hours at Watkins Glen.

When I think back, as to reflect on my experiences here, [00:13:00] coming here even today, it’s like visiting an old friend. It’s such a familiar place, even getting up here is familiar. The roads, the surroundings, the town. It’s been so many years of this being a part of my life. Just this past couple of months ago, we had a Rentsport reunion.

At an autograph session, I was sitting next to Terry Bootson, who he and I became friends as a result of he was driving for Champion Racing in the 9 11s at all the racetracks, but it was funny, he came up here, came over to me and said he had never been here before. This is Terry Bootson, a well known, effective F1 and sports car champion, and he asked me, what’s the track like and all that, and I pointed out the different aspects of the boot and all that.

After the race came up to me, he says this is the best racetrack I’ve ever driven. He said, I’ve never experienced a track where you can get such a great rhythm and go so fast. Enjoy the change in the elevation, but also the passing zones, the pit area. It was just a great experience. I felt great about that because that’s exactly how I [00:14:00] felt.

But having a guy like this who’s raced every fathomable racetrack except this place, coming to me and telling me, Rob Dyson, who came here in 1963, he’s telling me what a great racetrack it is, as we both get out of our cars. The heritage of this place, personally, that I’ve experienced, the victories of mine and my son, when I think back on it, it’s a gift to win a car race.

We’ve also been here for the tragedy, too. And everybody can remember some of the F1 incidences that have happened here. Francois Severt being the highest profile. I was here also when Graham Hill damn near got killed, broke both his legs when his car went end over end up in the back straight because of a suspension failure.

But I think the other thing I want to reflect on is how important the International Motor Racing Research Center is. I finished a race up here. We had one in the mid 80s, and Jean Argettsinger came up to me at the end of the race, and she said, Rob, I’m raising money at the Watkins Gunn Library to start a motor racing [00:15:00] library for the world to be able to come and do research, and it’s going to be done out of the Watkins Gunn Library.

And I was wondering if you would want to contribute. Well, here we had just won, I think, about 180, 000, which is a lot of money, camel money. Needless to say, when a woman like that asks you for money, you respond. And that was my first gift to the International Motor Racing Research Center. And it’s the gratitude that I have for the Argett Singers, for creating it and then preserving it, and then seeing how it’s been changed and how it’s improved over the years.

The bottom line here is that Watkins Glen is different than all the other racetracks. Because of its age, and because of its heritage, and because it’s the same place that everybody raced on, Formula 1, Can Am, sports cars, Indy cars, all happened here. It’s a wonderful place. The Research Center has been a remarkable resource for so many people, and I’m honored to have been a part of it.

And I’m honored to be here today, and I thank you very much. [00:16:00] Any

questions? Questions, anybody want to? I’m an old racer, so speak up. From the transition from being a race fan, to being a race driver, to then being a race father, what is your favorite stage? All of them. At the time, everyone seemed to kind of work. Truly the, an evolution of a racing career, I guess you could say.

Actually, it wasn’t until I was asked to do this that I actually started to put my thinking together. That really was, it’s the evolution of a racing career. There are very few drivers that are driving in cars, that are racing cars, that didn’t start off as race fans. I find it hard to believe that they wouldn’t have had some kind of inkling that they wanted to go racing at some time or another, as kids or whatever.

What it was is, it’s the evolution of a race fan. Becoming a race driver. I mean, it was important for me to get out there because I figured [00:17:00] I was 27 years old. I didn’t have any kids. I just came out of grad school. I had just started my broadcasting business. And I said, I’ve got to do this if for no other reason, but to say that at least I understand what’s going on.

But that was in 1974 and I’m still doing it. I’m not driving cars, you know, the race job, the race team, all of what’s going on. I’m going to do it up to here. And then with all the other things I’m doing with the Speedway Museum and the Research Center, which Chris is now a part of, it never ends and you don’t want it to end because it’s such a captivating sport.

I mean, it’s just interesting and it is all stories. Anybody that’s here can relate half a dozen stories about this place. Whether you were at the bog or whether you were, you know, watching or seeing Jim Clark or hearing the mattress go up the back straight, watching the IndyCars in the 70s and 80s. I mean, it’s just, you know, uh, it’s stories, it’s memories, it’s things that you’d rather [00:18:00] be here than anywhere else when you were here.

That’s the way I felt at every racetrack, and it’s still the way I feel. And ever I go through the gates of a racetrack, after all these years and after all these races, whenever I go through the gates of a racetrack, my heart just beats a little quicker. And why is that? Because it’s so goddamned interesting.

And you know that there’s gonna be something that’s gonna educate you. Something is going to give you a sense of more awareness of something. And this place is one of the best places, in my opinion, the best place to experience that. Thank you all very much.

This episode is brought to you in part by the international motor racing research center. It’s charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motorsports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center [00:19:00] welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives.

org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media [00:20:00] platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies.

As well as keeping our team of creators fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Learn More

This episode was brought you in-part by the International Motor Racing Research Center who’s charter is to collect, share and preserve the history of motorsports, and stories like those of Rob Dyson. The IMRRC’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world. And welcomes serious researchers and the casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more, be sure to check out www.racingarchives.org or follow them on social media @imrrc

During his 21 seasons as a professional racing driver Dyson drove in 92 races, scoring four overall race wins (including the 1997 Rolex 24 at Daytona) and a total of 18 podium finishes. Dyson continued to compete episodically in professional racing through 2007 and today remains active driving his collection of vintage Indy cars in a variety of demonstration events.

He was named chairman of the board of directors of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum in 2021 following a decade as a member of the board, he is guiding the institution through its $89 million transformational renovation as it charts its future path as the repository of the history and related artifacts of America’s oldest active and most storied racing facility. And he’s still involved in the Dyson Racing Team, supporting his son’s racing efforts, including Chris’ three attempts in ’04, ‘09 and 2014.

Rob’s Keynote Address

The 7th Annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History was held at Watkins Glen International on Nov. 3rd and 4th, 2023. Rob Dyson, the Keynote for the event, presented “A Driver’s Reflections on Watkins Glen at 75.” An appreciative crowd gathered to listen and the IMRRC was extremely grateful that Mr. Dyson made the trip to Watkins Glen to join the conference.

There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.

We hope you enjoyed this presentation and look forward to more Evening With A Legend throughout this season. Sign up for the next EWAL TODAY!

Evening With A Legend (EWAL)

Evening With A Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to Legends of the famous 24 Hours of Le Mans giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

ACO USA

To learn more about or to become a member of the ACO USA, look no further than www.lemans.org, Click on English in the upper right corner and then click on the ACO members tab for Club Offers. Once you become a Member you can follow all the action on the Facebook group ACOUSAMembersClub; and become part of the Legend with future Evening With A Legend meet ups.

|  |