Our guest tonight is the daughter of a Super Late Model team owner and a former Boeing engineer. She has worked for Roger Penske’s NASCAR and NTT INDYCAR SERIES programs since 2015, experiencing success at the highest level of motorsports.

But what Lauren Sullivan experienced with Beth Paretta’s female-powered “500” team at Indianapolis Motor Speedway stands as the most impactful moment of her career. And she’s here with us on Break/Fix to share her Motorsports journey with you!

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

|  |  |

- Spotlight

- Notes

- Transcript

- Highlights

- Learn More

Spotlight

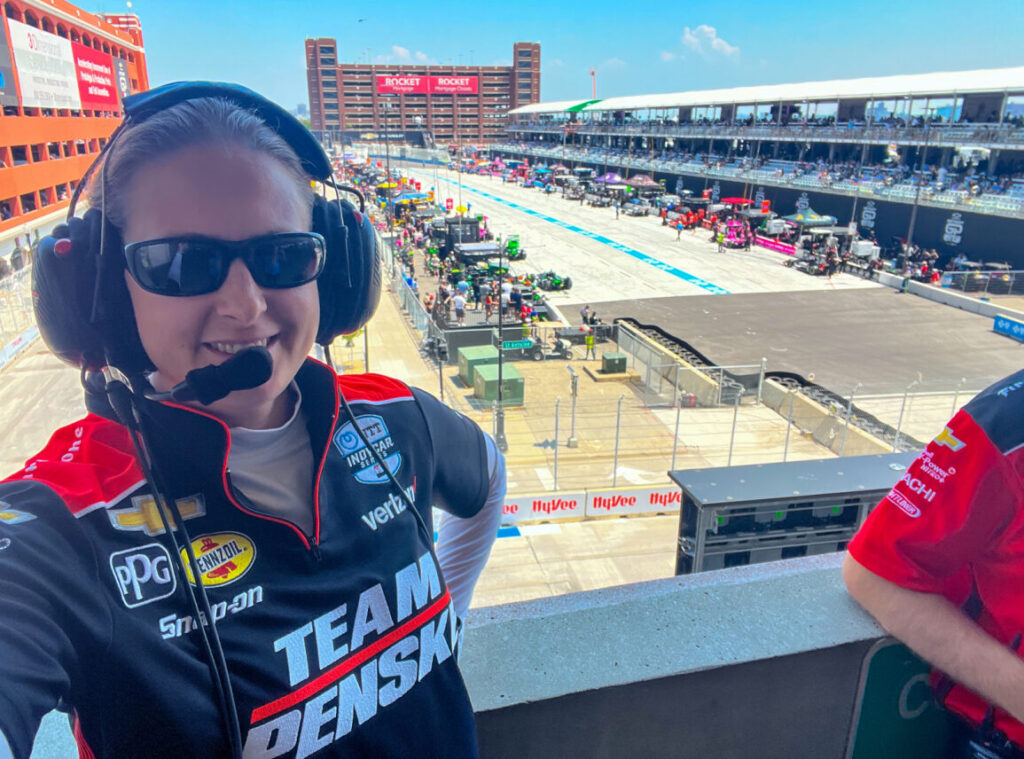

Lauren Sullivan - Aerodynamicist for Team Penske

Supporting the first female-forward IndyCar team, Paretta Autosport, at the Indianapolis 500 as a performance engineer.

Contact: Lauren Sullivan at lauren.sullivan@teampenske.com | N/A | Visit Online!![]()

Notes

- You came from a Racing Family – your family was into Super Late Models. What was that like growing up going to the track? Lots of kids “phase out” and maybe don’t follow in their parents footsteps, what drew you in? What helped you stay committed?

- Tell us about the Road to Penske – how did you go from Super Late Models to Boeing, to NASCAR, then Indy Cars.

- How much of what you learned in Aerospace carried over to motorsports?

- Not only have you worked as an engineer, you’ve also moonlighted as a spotter for folks like Josef Newgarden – we’ve never had anyone on the show that was a spotter – let’s unpack that a bit; what does that responsibility entail?

- Who were the women at the time, as you were starting out that inspired or helped you build a career in motorsports?

- Let’s talk about the good, the bad and indifferent of racing – the business side of things.

- We had LSJ on the show in Season 3, to tell her story and share about WIMNA – talk about your role in the organization, how you’ve seen it grow, and its involvement in the motorsports community, but the good it’s also doing for ladies in the sport.

and much, much more!

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] BreakFix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autosphere, from wrench turners and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of petrolheads that wonder, how did they get that job or become that person?

The road to success is paved by all of us because everyone has a story. The

Crew Chief Eric: following episode is brought to us in part by the Women in Motorsports North America, a community of professional women and men devoted to supporting opportunities for women across all disciplines of motorsport by creating an inclusive, resourceful environment to foster mentorship, advocacy, education, and growth, thereby ensuring the continued strength and successful future of our sport.

Our guest is the daughter of a super late model team owner and former Boeing engineer. She has worked for Roger Penske’s NASCAR and NTT IndyCar series programs since 2015.

Lauren Goodman: But [00:01:00] what Lauren Sullivan experienced with Beth Paretta’s female powered 500 team at Indianapolis Motor Speedway It stands as the most impactful moment of her career.

And she’s here with us on BreakFix to share her motorsports journey with you.

Crew Chief Eric: And with that, let’s welcome Lauren Sullivan to BreakFix.

Lauren Sullivan: Well, hello to you both. It is great to be here.

Crew Chief Eric: And I have to introduce Lauren number two. That’s Lauren Goodman, supervising producer of media and exhibitions for the Revs Institute.

So welcome back to BreakFix, Lauren. Well, thank you. So like all good breakfast stories, there’s a super heroine origin story. So Lauren, in the intro, we talked about how you came from a racing family, but what was it like growing up at the track? And one of the things I want to also highlight is that a lot of kids phase out of that lifestyle as they get older and they don’t follow in their parents footsteps.

So what drew you in? What helped you stay committed to motorsport?

Lauren Sullivan: Growing up, I was always around motorsport in some form or another at a really young age. We would go to the [00:02:00] NHRA Winter Nationals in Pomona, California, which wasn’t too far from where I grew up. When I hit about fifth grade, my family started a super late model team at Irwindale Speedway.

As soon as I hit 16 and was old enough to be in the pits, I was right there doing what I could to be involved with the car. And that’s kind of where the passion First ignited and to me, it was always just a hobby. It wasn’t ever something I was going to make money at.

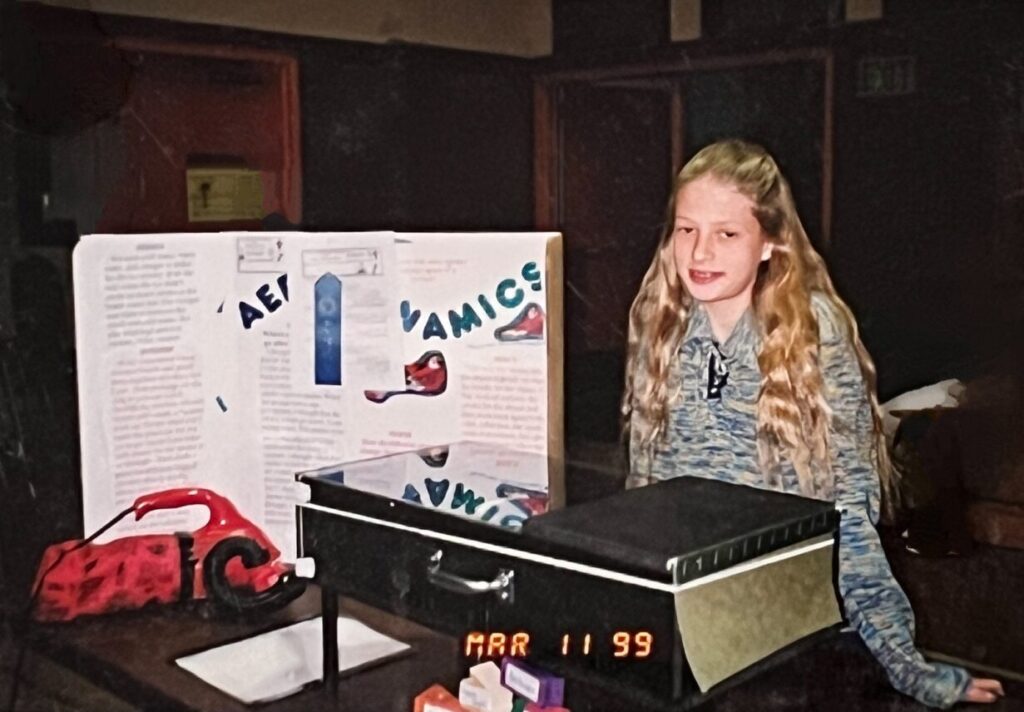

Crew Chief Eric: One of the things I find fascinating about your story, and it’s a thread that you and I have in common is right at that middle school, early high school period, I too did a science fair project about automobile aerodynamics in a slightly different way.

I had no intentions on going to work for Boeing or anything like that, but I was inspired by Giorgetto Giugiaro because I wanted to design cars. And so I saw that come up in another interview of yours where there’s pictures of you at the, you know. 7th, 8th grade science fair with your aerodynamics project.

What about aerodynamics at that age, 13, 14 years old, got you excited.

Lauren Sullivan: It was the ability to see what you can’t see or to understand [00:03:00] what you can’t see. Once we did flow viz in this one tunnel that my dad helped me build and I could see the flow around these different objects we were testing. Like, it was just like a light bulb of like, I can see what I can’t see.

And I can make decisions with this information, you know, from there. I was like, well, what else can you see the flow around? I didn’t know then that what I was doing was engineering. And I didn’t even realize the one subtle connection I had to my middle school project till I think after Boeing or in the middle of Boeing, like I’d forgotten about that completely.

And then I saw it in a scrapbook my mom had put together and I was like, Oh my gosh, this path makes so much sense. Now it’s always been where my interest has been. So. Going into high school and then college, I was always geared towards science and math and did the science thing in high school, but there weren’t any robotics clubs back then or anything like that that I could do that was motorsport except my family’s race team.

And then in college, I decided to major in engineering and the school also had a formula society of automotive engineers. program or FSAE. And I got involved with [00:04:00] that. I got to continue motorsport in that way. But at the college I went to, Parks College of St. Louis University, everyone kind of ended up at Boeing because Boeing is right there in our backyard in St.

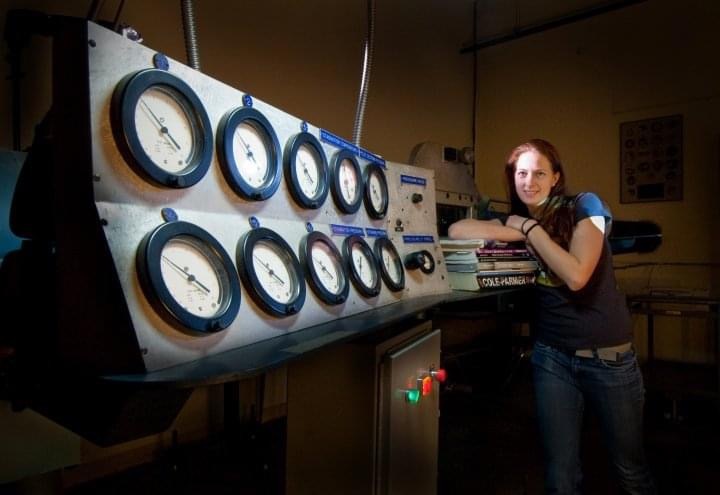

Louis, at least Legacy McDonnell Douglas is. And I was an aerospace major. And so that was kind of like the conveyor belt, if you will, Boeing hires, a lot of parks grads. And to me, it never dawned on me that I could make my hobby, my career. So even being involved in motorsport, all those years, I set my sights on what I like to do within aerospace engineering, which was wind tunnel testing.

That’s where my passion within the engineering field is upon graduation. I got a job with Boeing as a wind tunnel test engineer, and I did that for about five years. And then kind of just got to a point of like, I don’t think I like airplanes after all this time. Like I don’t mind flying in them or anything like that, but it just wasn’t exciting to me as much as I thought it would.

So I was kind of having a moment of like, what would I do for her to change? And I’m like, the only thing I’m. Good at or that I know how to do is wind tunnel testing. And I’m like, [00:05:00] man, well, I wonder if they do that in racing. It’s just a hobby. I can, you know, we’ll see. So I, I start Googling like wind tunnel testing and motorsport.

And of course the results just like lit up like, Oh, okay. We might be able to do something here. So started applying to jobs. Really, again, just not thinking this is going to be a career path for me of all the teams I applied to and all the motorsport wind tunnels I applied to. I only heard back from Penske, but I heard back twice.

I first heard back from the aero department on the NASCAR side. And then like within a week or so, I heard back from what’s called Penske technology group, which actually runs our scale model wind tunnel. And I was confused for a second. Cause I didn’t know about PETG at the time. And was like, why, why is Penske calling me twice?

And then Someone finally explained it to me. So once that kind of merged into one, I was hired at Penske to be a wind tunnel test engineer for their NASCAR program. Actually, it started out as a, just a general aero engineer, design engineer, doing some CAD for them. And then once I started doing wind tunnel testing over the [00:06:00] years, I started essentially leading the full scale testing efforts we would do.

In 2021, Tim Sindrick, who’s the president of Penske, reached out to me and asked if I’d be interested in helping this female forward team that Beth Paretta was putting together for the Indy 500. I immediately jumped to that and said yes, not having any idea what I was getting into or what was about to unfold.

Growing up with the super late model team and stuff like that. I was always NASCAR, always NASCAR. It’s rather ironic because I actually met my husband at parks college on that race team. I was in, we were friends for about nine years before we did anything about it. So we’re just friends through college and all that.

But way back then he was like, you would like open wheel. You would like open wheels. Like, no, no, no, I’m NASCAR. I’m NASCAR. I’m not doing open wheel. I’m doing stock car. I came back from the Indy open test. That’s in April. In 2021 and looked at him. I was like, I really like IndyCar. And I think I want to switch.

At that point, he was like, I’ve known you for 16 years, 16 years. I have been telling you, you would like IndyCar. So [00:07:00] then I went to my management at the end of that year, after the 500 and said, Hey, if there’s. A spot over there I’d like to switch and explore a management path of some kind, see what we can do.

Nick came back and said, how about a engineering and team logistics coordinator for our IndyCar team?

Crew Chief Eric: And here we are. You know, as you were coming up through the ranks, evolving your career from aerospace, Into motorsport, who were some of the women at the time that you were looking up towards? Who were the folks that inspired you or helped you build your career in motorsport?

Lauren Sullivan: When I look back, first and foremost, definitely my mother. She instilled the knowledge in me that I can do anything I wanted. Nothing was off the table. And she supported me with all the different things I tried over the years. She kind of taught me never take no for an answer. Just find another way. But I would say in general, what was a motivating factor for me coming up through the ranks was being other women be the only one in the male dominated field.

I was drawn to people like Amelia [00:08:00] Earhart and stuff like that and found that in motorsport engineering. And what I have learned is how much I don’t want that in terms of how much I don’t want to be the only female and how much I want other women around me. So even though What I liked seeing was like the girl with all the boys in terms of just being able to do what they say you can’t do, if you will, I realized that like that image needs to change and there are still sometimes I see it where there’s other women I’ve come in contact with in engineering, motorsports, stuff like that, that.

Want to be the only female and feel threatened when there’s others around them. I’ve just come to realize that that is not how you succeed. And to the point now that, like, it’s frustrating to me to see any situation where there’s only one token female, if you will. If I really, like, dig into my spiky, I guess.

Probably what was driving me was that I don’t want to see this only female anymore. Like we need to upset the status quo. Cause that’s all I [00:09:00] did see back then was the one female wherever I was, if it was motorsport or math or science engineering related, that was all I saw. Now I don’t see that and that makes me happy, but I want to see it even more.

I want to be seeing equal distribution.

Lauren Goodman: We are all on the same wavelength. 100%. My background before I came to Cars was the film industry. It’s the same thing. Yep. So I want you to tell me about the first time you met Beth Perretta.

Lauren Sullivan: I remember being nervous because it was Beth Perretta who like, I could already sense this is going to be big, especially when like, Cendricks come into you and like Roger wants to do this with Beth.

It’s like, okay, this is big. And I just remember the anticipation of talking to her on the phone for the first time. And after I got off the phone with her, I was like, that was just like talking to a friend. We were talking only pretty much about motorsport and a little bit about my history because she’s trying to get to know me and know what to expect out of me at the Indy Open Test and at the 500.

But it was just like, man, this is someone I can relate to. It really energized me because I was like, oh, this is, this is good. This is not a [00:10:00] dog and pony show. This is not. Someone’s seeking attention. She is genuine about this. This is in full alignment with me. And like, I have this huge passion for outreach and just taking any opportunity I get to speak to the next generation, especially girls.

Once I realized that there wasn’t any ulterior motive at play after she and I talked, I was like, Oh, this, this is good. Not only am I excited to do this, but I’m behind this.

Crew Chief Eric: And you said jokingly that, you know, you were kind of tired of planes. You want to move on to other things. As you transitioned into motorsport, how much of aerospace carried with you into motorsport?

How much of it is relatable and how much of it did you sort of just check at the door?

Lauren Sullivan: A lot of it’s actually relatable. IndyCars specifically, especially when they’re at IMS or just upside down airplanes. What’s holding them to the track downforce is the same thing that’s pushing an airplane up, which is lift.

Just a sign convention change. Honestly, at that point, cars have lifting services again, if we’re going to just focus on an IndyCar front wing, rear wing, you have those main lifting services and airplane has lifting surfaces. There’s things that [00:11:00] induce drag on it. Halo induces drag, the mirrors induce drag on an IndyCar, stuff like that.

So at a. Not even too high of a level. There’s a lot of the same concepts at play. The more you put it at a basic level, they’re almost identical. It’s just a different shape, a different form and understanding that. The only, what I would consider the biggest difference between the two is the presence of the track.

With the car and how those two interact in aerospace and wind tunnels, we call that wall effect or ground effects because when an airplane’s in the sky, there is no influence from anything around, or we hope not, at least there’s no influence from a ground, a wall or anything like that. And once you start to bring something like that close to a lifting body, an airplane or a race car, the math changes and how the forces generally react changes and the flow structures change.

So that’s the biggest difference, but there are parts of the car that are completely out of that effect too.

Lauren Goodman: This is fascinating to me because of course, as a F1 fan, ground effect is a triggering [00:12:00] word. It sends us into spasms. Don’t you know, here’s what I want to know about IndyCar specifically as its own series, when it looks at the idea of ground effect and because IndyCar is my understanding is because all of the chassis are Dallara.

A lot of that like balance of performance is really equalized across the teams. So you as an engineer, especially having a background in aerodynamics, where is it that you can find the little advantages? What parts of the car represent opportunities? That’s the elusive question.

Lauren Sullivan: Well, like you said, Since it’s single source supplier for a lot of the parts on the IndyCar, it would appear that you lose a lot of the ingenuity advantages that teams have with engineering testing and thought.

There’s a lot to be said in the margins. It’s all the same parts, but how you fit them together, how you make them together while mating two parts together seems insignificant when you multiply that across the entire car, it can be significant. And on top of that, you have very sensitive surfaces. [00:13:00] Some areas of the car are insensitive and others are extremely sensitive.

Once you can identify those areas on the car, then you kind of know where those margins matter. Then you can even get into like how you prep it. Just again, it’s in the details. It’s really bringing all the details together. One thing I do talk about a lot is like, okay, when you’re in a wind tunnel, you have an error band.

And so it’s kind of like, yeah, we said something’s 10 pounds, but it’s probably plus or minus two pounds. And so when you find something that’s like a pound, it’s hard to say with certainty if it’s worth a pound of downforce or not if your air band’s two pounds. But if you have five different things that are worth a pound, if you put them all together, now you have five pounds.

Now you’re outside that error band. It’s finding those sensitive areas and they’re not always obvious. And then exploiting them in the margins and the details. Do

Lauren Goodman: you think your background in NASCAR really helped with that?

Lauren Sullivan: I do actually, because when I was in NASCAR, that’s when the Hawkeye system rolled out, NASCAR went from checking with just templates where the name of the game was.

Okay, if the template fits here in X and if it’s here in X, whatever you do in [00:14:00] between doesn’t matter. And you had, you had a lot of room to play, I guess I would say, because it was like the template fit, but it had to be plus or minus 50 thou, which doesn’t sound like a lot. But if you like move the anchor point where that template aligns by 50 thou, well, three feet down the road, it’s way more than 50 thou.

But then they moved to the Hawkeye system where they were scanning the car. And you’re thinking like, okay, now everything’s way tighter. Well, there was a huge learning curve there too, just with how to use this Hawkeye system and what it could see and what it couldn’t see and stuff like that. So, but that’s where it got into again, the margins and the details.

And so then going over to IndyCar, where it is a single source supplier, you’re already in that mindset.

Crew Chief Eric: Lauren brought up Formula One and you know, you hear it all the time, especially the last couple of years, if only we had unlimited wind tunnel time, like we used to have. And I sort of wonder, There’s a setup for every track.

Does the aero really change that much from track to track? I can imagine in the IndyCar world, it probably does because the brickyard is going to be different than some of the smaller ovals versus running at, you know, Watkins Glen or at the street [00:15:00] courses. St. Pete. Exactly. Would it really make that big of a difference if they had unlimited wind tunnel time in Formula 1 again?

Lauren Sullivan: So it’s hard to say because I’ve seen a series go from unlimited to limited. And when I started at NASCAR, it was unlimited and we were there. All the time and now NASCAR is limited on wind tunnel testing and it was when I was there too before I jumped over to IndyCar. Yes, track to track is wildly different in some respects.

Again, there’s always parts of the car that are kind of insensitive to the track or the ground effects, if you will, especially talking about different speeds. The thing with the wind tunnel, though, is. You can’t really change that. You don’t have a wind tunnel for St. Pete. You don’t have a wind tunnel for IMS.

You don’t have a wind tunnel for Barber. What you have to do instead is understand where the car is at in relation to ground effects, or in relation to the ground, rather. When you’re at those tracks, I get some tracks, you’re sitting way lower, some tracks, you’re higher. And therefore you put the car at those averages and then get data at these averages.

And then you try to extrapolate and [00:16:00] interpolate to where the car is actually going to be when you’re at those tracks. Having more one funnel testing time helps because that database can be bigger and also more refined. You have more data to rely on and you can try more. Things where I see it start to diverge from an advantage is honestly on the business side of things.

What happens is the teams with money are the ones then producing this huge advantage and it kind of allows the field to run away from itself or diverge because then the teams without a lot of resource to do all this one tunnel testing aren’t having that same advantage. You just get repeat winners. So in a way, it’s like its own DOP.

Crew Chief Eric: In the advent of generative AI, let’s say you were to take previous data sets, current data sets, put it all together and let the AI munch it through. Aren’t there only so many shapes of the wings and the spoilers and the body itself? There’s only so many permutations there. Wouldn’t an AI based assistant be able to help you generate those numbers and those setups that you need without having to resort to more wind tunnel [00:17:00] time?

Lauren Sullivan: So it would probably help where it’s not going to help. And honestly, we’re a one time that might not even be as helpful. It’s just kind of the unpredictability

Crew Chief Eric: of weather

Lauren Sullivan: weather’s one of them, but like just on track interactions, you are talking, whether you’re talking dirt, you’re talking to car in front of you, a car beside you, and yeah, you could probably put all of that into AI, at least putting a car in front of you and stuff like that, which you’re not capturing as well is.

tire rubber buildup on some of these surfaces and any damage you happen to get or anything like that. So there’s still a lot that having a general database of data to rely on would help with. And I think AI would help probably create a Baseline. I’m not sure it can predict real life racing with all the different systems that are going on.

Crew Chief Eric: Lauren pointed out, you know, obviously an open wheel car, like a formula car and Indy car is going to be more sensitive to a lot of the things you’re talking about, but if you kind of look at a NASCAR and it reminds me of, you know, when we built RC cars as a kid, you know, you kind of slap a different body on the same.

Yeah. [00:18:00] It’s also something that we can relate to as drivers of everyday cars. It’s hard for us to relate to an open wheel car because you know, you can’t drive those on the street. But if you think about a NASCAR, it’s like, well, it’s sort of a brick on wheels. It’s not a Volvo of the eighties, but there’s these arguments to be made about design language these days that there’s only one design that cheats the wind.

And so if you look at supercars and hypercars, they all kind of look the same, whether it’s a Ferrari or the new Corvette or the NSX. Then you have Chrysler coming to the table with a challenger that looks like it’s straight out of the 70s, making gobs and gobs of horsepower. And it’s like, well, how aerodynamic do these cars really need to be on the street?

So how do we compare and contrast what we’re seeing at the racetrack to what we’re getting on a Monday morning when we go buy a new car?

Lauren Sullivan: A lot of consumer car technology starts in racing on multiple different fronts, whether it’s materials or the manufacturing process or the design process, you know, racing is a great test bed because it’s to an extent a controlled [00:19:00] environment, not always, but you know, Firestone and IndyCar has been trying out renewable rubber and the sidewalls of some of our alternate tires at street courses.

And before that ever makes it to consumer tires. They’re running it through its paces and racing same with like oils and fuels, like shell went completely renewable with IndyCar last year, even some safety things too, with how they reinforce certain areas of the chassis. There’s a lot of those fronts where you’ll see aspects of racing translate over to consumer vehicles.

And again, back into the design process, like some of that gets fed into it as well. From an aerodynamic perspective, there’s a lot of systems that feed each other. They’re like, for one, I’ve, you know, over the last several years, I’ve seen 18 wheelers evolve. aerodynamically. You see these skirts that they have underneath now, or these flaps at the back that they have, and all of those are determined in wind tunnels.

And it’s the same wind tunnels that we use in motorsport, but like the need for a rolling floor wind tunnel was kind of demanded by motorsport because we needed to find a way to [00:20:00] test our cars without going to a track. There’s other things too, just like the general aerodynamic structure of like, where to put the mirrors, what shape they should be, things that are big, like what we call needle movers for drag and stuff like that, that can also come into play, as well as the underbody form, because we call that the underwing in IndyCar, because it’s perfectly smooth.

For the most part, and now NASCAR kind of is too. And actually when NASCAR wasn’t smooth under there, and it was a lot more stock in the underbody, there was a lot to be discovered with like where you are actually getting dragged because you have a gap between your exhaust pipes and stuff like that. So a lot of that does eventually translate over to consumer cars in that respect.

That being said, the speed most. People typically go in a consumer car is not going to be the speeds you obviously see in an Indy car. And therefore a lot of this stuff can become irrelevant because some things only matter when you’re going over 200 miles an hour, which don’t try that at home.

Crew Chief Eric: How far are we away from what I like to call Star Trek technology?

And you’re [00:21:00] starting to see this on a lot of the Teslas and I’m going to single out the Cybertruck because it originally was intended. Not to have mirrors and you’ve brought up mirrors more than once. And the reason I’m bringing that up is because they’re using combinations of LIDAR cameras and other sensors.

Is that going to find its way into racing where one day you’re not going to have mirrors and maybe it’ll be in the helmet or on a heads up display?

Lauren Sullivan: That’s a good question because my next question is then if you can put that amount of technology in a race car, that’s fast enough, because I will say with something that is.

It’s transmitted, which something like that is a transmittable piece of data. It has to be fast enough for the driver to receive it and process the information as things are unfolding. So while on the road, an 18 wheeler doing 65 miles an hour, if its cameras see something and then send it to its display, that has to be able to happen faster when an IndyCar is going 200 miles an hour.

And so let’s say, okay, we outfit IndyCars with these sensors, so you don’t need mirrors. Do you need spotters then? Because at IMS. [00:22:00] We’re required to have two spotters when we’re on the oval. You know, they’re the eyes in the sky for these drivers, the human reaction to seeing something and even seeing something come together before it happens can be critical.

So that would be my next question is if we get to that point, how would it be used? Would it eliminate spotters from the industry? It’d be interesting to see.

Crew Chief Eric: Do you think it could also be used to determine if there’s like dirty air, if somebody’s running too close, where the optimal distance would be to catch the draft or something like that?

Could you see it being used as an advantage that way?

Lauren Sullivan: Press reports would see that over cameras because press reports are what are used to pick up flow and like see what you can’t see. So the camera system, if we’re going to talk about that, where it simulates your mirrors for you, I can see it more for behind the driver and like telling them what’s coming versus what’s ahead.

Cause I will also say that’s kind of why there was some chatter initially when the new halo at arrow screen came out. It has saved countless lives since it came out. There’s a huge improvement. , but the drivers could feel the air from the car in front of them and know where to [00:23:00] put their car based on the drag bubble as it’s called, or the wake that they could physically feel.

And so it’s hard to replace that. No delay there. There’s no transmitting of data that has to happen when you’re feeling it’s as fast as your brain can register it.

Crew Chief Eric: You’ve mentioned spotting and how crucial that is in how it takes two spotters at the Indy 500. I heard that you’ve also moonlighted as a spotter, so sort of other duties as assigned, and you’ve done that for Joseph Newgarden and some other people.

What does that responsibility entail? You know, we’ve never actually talked to a, an official spotter before. So what are you doing? What are you signaling to them? What are you looking for?

Lauren Sullivan: So it depends on the track ovals are definitely an IMS in particular is a much different beef than. Road course and street course.

For example, let’s say Texas and St. Louis or Gateway. From one spotter stand, you can see the entire track and you can always see the car. At IMS, with how big it is, where the spotter stands are, you cannot see the car around the entire track, which is a problem because you have to be able to pick it up as it comes out from behind a tree or something like that.

And then with road course [00:24:00] and street course, it’s even more complicated in terms of seeing your car because. None of those tracks, you can see everything. So typically you’ll stand at one of the trickier parts of the track for them or where there’s going to be a lot of passing because that’s when they want to know if someone’s gaining on them and if they’re looking to pass them high or low or something like that.

The main overarching responsibility of being a spotter is to be a second. pair of eyes for the driver on the track, but let him know what situations are unfolding around them. So you’re looking both ahead and behind them, behind them for who’s coming and ahead for any wrecks that are happening. Because if you can see a wreck and let them know ahead of time if they need to go high or low.

is crucial because they will just trust you and put their car there to know that’s how they’re going to get through if they can’t see it and register it in time. The drivers rely on the spotters to paint the picture of what’s going on on the track around them. So you give them the information, let them make the decisions with the information of what they want to do.

You know, you don’t tell them, okay, pass this guy. You just say he’s going high and just leave it at that. And he knows he can go low. You give them the [00:25:00] information. You let them decide what they want to do with it. At tracks where it’s extremely high speed, like IMS and the other ovals, it’s even more crucial to look ahead to where they’re going versus what’s going on behind them or even around them at that moment.

Because they’ll know who’s around them, especially at IMS. If they’re coming out of Turn 4 and there’s a wreck in Turn 1, it is so fast that they’re going to be there. It’s unbelievable. You honestly can’t even get on the radio and tell them, go low in Turn 1 before they’re in Turn 1 when they were in Turn 4 when the wreck happened.

Paying attention to a lot of different movements, things, information at once, deciding what’s the most critical information that the driver needs to know in that moment, and communicating it in the least amount of words possible.

Lauren Goodman: I love American motorsport. I love European based motorsport. And in Formula One, it’s all one person telling them this.

And in IndyCar, you have a spotter who’s live eyes. It is. Truly, I think almost an analog process. It is not based as it is in formula one, like just reading data [00:26:00] from whatever transmitter. It’s somebody with a pair of binoculars being like behind you in front of you. Do you think that’s superior in a way?

Because in formula one, they have problems all the time with them saying, you didn’t tell me so and so was on my rear left trying to pass me. Do you feel like just having a human element there? Is better in IndyCar?

Lauren Sullivan: I do, especially at these higher speed tracks, just cause as a human, you can multitask and like literally you can stand and be watching your car come in your peripheral and watching turn one and your other peripheral and like You’ll learn when something doesn’t look right, even though you’re not looking right at it, and you’ll know you need to jump on the radio and say something.

There’s also a relationship that starts to develop because some drivers want constant chatter and want to constantly hear from their spotter, and other drivers want you silent unless somebody’s in the wall. You have to learn their preferences and kind of what they want to know or what they need to know.

Like some drivers like, yeah, as soon as there’s another car, like 10 car lengths back, I need to know he’s there. And other drivers are like, just let me know when someone’s going to pass me. And there’s also an advantage kind of knowing [00:27:00] if we’re in our, any rivalries even exist. Sometimes you’ll just let them know there’s a car coming versus which car is coming.

So they kind of know, okay, that’s a rookie. I’m going to give them some space or I race this driver pretty well, so we can go at it. So I think there’s a lot of those subconscious decisions that go on from the spot or two, like kind of just knowing everything else that’s at play. The

Lauren Goodman: human element.

Lauren Sullivan: Yes.

The human element for sure. And it even comes into inflection in your voice. Sometimes there’s one driver, I think it was Rick Mears. Who said the best spotter they ever had was someone who had a different inflection for inside or outside, even though they’re still saying inside or outside, the word didn’t have to register because what was registering was the inflection of their voice.

Crew Chief Eric: It’s sort of like when you’re coaching at the track, you could be like, we’re going into turn one, a little too hot break. Or you can be like break, break, break. They’re going to instinctually press the brake pedal a little harder every time you get more excited.

Lauren Sullivan: And it’s funny because that’s the one thing you don’t want to do on the radio is get excited.

Crew Chief Eric: Good or

Lauren Sullivan: bad. I mean, you can get excited when it’s [00:28:00] good if it’s after the checkered flag. Especially with something bad, you literally want to be like, there’s five cars in the wall right now. They’re all sliding down, just go low. And you don’t even want to say right now that’s too many words, but you want to be as monotone as you can.

Because what’s been interesting for me to learn is how you can pass on energy and emotion on the radio just by how you say something. So you don’t want to make them panic any more than they already are just by hearing five cars in the wall. And actually, the more I think about it, you don’t even need to say that.

I’m going to say cars in the wall, again, the least amount of words possible. And that’s, What I’m still learning, what my phrases are for the same things you see over and over again, that is the smallest phrase to say it. Some people say, when they’re talking about the gap that a competitor has to you and there’s three car lengths back, they’ll either say three back or by three, which means the same thing.

I just say, whatever’s natural to me, because you don’t want to be jumbling up on the radio and you don’t want to be. Making it longer than you have to, something like that. I just now consistently say three back or five back, but there’s situations I don’t encounter all the time that I’m still learning of how do I [00:29:00] want to say this?

It’s also thinking ahead of, okay, I got a street course. I’m in this turn. This is all I can see the tracks. I’m not gonna be able to tell them anything else. How am I going to call a wreck there or how am I going to call a wreck here? What am I going to say? And like telling myself, this is what I’m going to say.

If that happens, just so I don’t have to think about it. And really it all becomes like a dance. Habit forming is what you’re trying to do with stuff on the radio.

Crew Chief Eric: You know, in all this talk of IndyCar versus Formula One and talking about your career, there’s a big question that we failed to ask you, Lauren, which is.

It’s obvious you’re working in IndyCar now, but what do you prefer working on the stock cars or the open wheel cars?

Lauren Sullivan: I prefer as an engineer, IndyCar, but I grew up with NASCAR and I think as a fan, I prefer NASCAR. Always loves the big wrecks and that hurts to say as someone who’s on the other side now and has to react to that kind of stuff.

Those big wrecks in IndyCar are not good. Whereas NASCAR ones are generally more show than damage or harm. I should say the reason I like IndyCar from an [00:30:00] engineering perspective is the amount of data we have on the cars and the amount of information we have from the cars to make educated decisions with NASCAR.

You don’t have that kind of feedback. If the driver says the car’s loose, you take his word for it, and you try to figure out what your normal knobs are, that’ll tighten up the car with IndyCar. If they say it’s loose, we can pull data and be like, yeah, no, you’re right, and it’s happening in this turn and it’s happening in this turn, and it looks like this part of the car.

We can make an adjustment here, and that typically makes the car go tighter for this part of the track. Just using the data and information available to make decisions is what draws me to IndyCar as an engineer,

Crew Chief Eric: as we all know last. year at the 100th Le Mans, NASCAR kind of shook the apple cart pretty hard with the garage 56 Camaro.

So that’s a leap and a bound when we go from the sixth generation NASCAR to the seventh as an engineer, what do you think?

Lauren Sullivan: I think it’s great. Cause I think it’s thinking outside the box and it’s situations like that, where you push boundaries, you push limits and you discover something new and that’s [00:31:00] often how new techniques, new.

Processes come about is from putting two things together. You didn’t think we’re ever going to be together.

Lauren Goodman: As a student of history and a lover of Lamont and working at a museum that has a lot of cars that went to Lamont, all I can say is Eagle Sound, Eagle Sound, Eagle Sound, because that is.

Crew Chief Eric: Having been there to see it in person, you knew where it was at any given moment on the set.

Lauren Goodman: And that goes back to Briggs Cunningham bringing American cars and Chrysler engines to Le Mans back in the 50s. And the French loved it. They were obsessed with it because where could you get that torquey, low American engine sound, except from the Americans.

Crew Chief Eric: Yeah. Wasn’t coming from anybody else. Yeah.

Let’s talk about the good, the bad and the indifferent of the racing industry. You’ve been in motorsport now for a number of years. You’ve seen it from different angles. You know, a lot of people fantasize about what it’s going to be like when they get there.

Lauren Sullivan: Cause it’s [00:32:00] funny. Cause I look at my life a lot of times and I’m like, who decided to trust me with this because I don’t trust myself with this.

Then you look around and realize like everybody else is asking themselves the same question. Some days you’re like, I don’t know how I got here and I don’t think I know enough for this. At the same time, then you look at it and it’s like, oh my gosh, we’re designing cutting edge technology. We’re racing at unbelievable speeds, right on the knife edge of disaster.

And so what to expect if you’re looking and you’re going to have probably a lot more fun than you think, and you’re going to work a lot more than you think. You know, a lot of people are relatable. It becomes a very close knit tight community for sure. Cause you’re on the road all the time with your teammates and with people on other teams, even.

I guess one thing that probably surprised me getting into motorsport. Was how much behind the scenes there isn’t the rivalry you see on the track.

Crew Chief Eric: You mean it’s not like Drive to Survive?

Lauren Sullivan: I mean, it’s, it’s interesting just, you know, the drivers is one thing, but like the crews that are just cross pollinated with [00:33:00] friends, if you will.

You know, like two teams can have a standing rivalry, but I’m going out to dinner with one of their engineers because she and I are friends or something like that. Like it’s, and you know, we won’t even talk about work. I think that’s probably what surprised me was like actually how friendly it is behind the scenes just because it has to be.

It’s a small community as it is. And What happens on the track days on the track a lot of the times

Crew Chief Eric: earlier, you talked about how things have changed in motorsport where it used to be like, you know, you were the only woman and now you want to see that change. You know, there’s more, there’s obviously a lot more women in motorsport than there used to be.

And then you talked about Peretta Autosport, which was touted as an all female team between the crew and the drivers and everything like that. That was an awesome thing for all of us to witness. There’s a lot of things that have springboarded off of that. And as a result of that, because the question is still out there looming, and it’s really not about gender in motorsport.

It’s really about making the paddock more diverse. [00:34:00] So how do we make motorsport more inviting for everyone?

Lauren Sullivan: You attack it from several different angles. I think there’s an obligation to, for individuals that are in motorsport and in particular in the paddock to make it a welcoming environment. When I see a new female in the paddock, that’s clearly on a team.

I will make a point to go up and introduce myself because you definitely get these just like we pass by each other. We don’t look at each other. I’m not sure if I’m supposed to like you. I’m not sure if you hate me already. Like that or not. I’ll just go up and be like, hi, I just wanted to say, Hey, and if you ever need to know where the bathrooms are, the good bathrooms, just come grab me.

I’ll tell you where they’re at. So just cause I wasn’t new to professional life when I joined Penske had already been in Boeing for five years, but I just remembered what it was like to be new and just kind of figure out my own way. And it’s like, for me, that’s not necessary. And if, when I see someone who’s learning again, I just tend to see the target, the females who’s new.

That I hadn’t seen the years prior, you know, I’ll go up to them. So they just have a friendly face that they can come reach out to if they need to. And so I think it even comes down to like, if we’re going to talk about [00:35:00] men, when they see new people, male or female, doesn’t matter. And I will say, if I see new men, I need to do the same thing.

Just going up and just saying hi to those people because there’s a lot of self imposed fear. This is across all lines, all gender, race, everything of I can’t ask questions because then it looks like I don’t know what I’m doing. It’s like, well, if you’re new, you’re expected to ask questions. But I think the barrier for a lot of people is feeling uncomfortable enough to do that.

One angle is just it’s on individuals to go up to it. Those who are new on their team at their work in the paddock that they see and just say hi and introduce yourself. I also think from a series perspective or a more global perspective, if you want to look at it that way, getting in classrooms sooner, I think it’s huge.

In fact, I was lucky enough to have that motor sport exposure when I was growing up, but nowhere in my academic career did I have it till I got to college. And so I actually made a point last year of going back to my high school in Southern California and giving a presentation on [00:36:00] motorsport. I started at the big top level, like you’ve got NASCAR, IndyCar, F1, NHRA, dah, dah, dah, and then dialed it down.

Sort of the different series, dialed it down into IndyCar and then dialed it into Engineering and aerospace and STEM, but then also touched on all the other careers that are in motorsport, because we have chefs that travel with us. We have doctors that travel with us. We have PTs, you have marketing, you have photographers, you have social media influencers.

It’s not just engineering and mechanics. There’s a lot more to it than that. And so try to like make kids realize if you have an interest in motorsport, but you don’t want to do the mechanical thing or the math thing, you don’t have to, you can still be in motorsport and do something else. But I wanted to do that with my high school because The only reason I knew about it back then was because of my family’s hobby.

And I think the younger we put that in front of kids and the more it’s in their thought as they’re making decisions on what high school to go to, what clubs to be in, what the college and university to go to, what to major in as they’re making those decisions and they know what those options are. And I think if they [00:37:00] see that as an option for them and it’s achievable and it’s not out of reach, like, Oh, well, I’m not going to get an engineering degree.

I’m not even going to get a college degree. You don’t have to be in motor sport. You can go to a trade school.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, what I think is interesting about this point that you’re bringing up, Lauren, is Maybe sometimes motorsport has a stigma associated with it and it keeps people at arm’s length and maybe we need to sort of change the narrative and say, it’s not about motorsport.

It’s about the evolution of mobility, moving people around. And that’s where you can bring in. The engineers and the physicists and the chemists and the artists, you know, we can talk a little bit more about steam rather than stem at that point. Right. People sometimes relate cars to appliances and it just gets under my skin and I start to boil and I’m like, do you understand that?

It’s not one person that pens a car. It’s a team of people, whether. Scientists and engineers and artists and everything that goes into that. It’s such a beautiful piece of the human element as Lauren likes to call it. There’s something to [00:38:00] behold and something to wonder, but they also give agency to the past.

When you look at how cars have evolved, they probably evolved more than anything else in the history of the planet.

Lauren Sullivan: So the A in STEAM or the art that is involved with science, technology, engineering, and math is critical. And it really is critical because, you know, I’m 35 years young or old, however you want to look at it, whatever side of that you’re on.

But I’ve done a lot of things from school sports and, you know, motorsport and engineering and the clubs I’ve been involved in. It’s pretty varied and never, never had I, have I seen success in a silo. And what I mean by that is I’ve never seen. An engineering project succeed without creativity and some form of art involved.

I have never seen a race team succeed without a marketing department. There’s this codependent relationship between art and science. If you want to just put an umbrella over science, technology, engineering, there’s a codependency and they each need each [00:39:00] other. So much so that if one exists by itself in a silo, whatever is being applied is not going to succeed because it’s not going to have this other element that it needs.

Especially motorsport. We see a lot of the arts come in through the obvious like marketing and social media stuff and graphic design and photography and so forth.

Crew Chief Eric: But it’s even in what you’re doing because aerodynamics in a way is more akin to art and engineering too.

Lauren Sullivan: Oh yeah, especially when it’s like an empty slate.

It’s how you’re gonna create this idea from nothing, if you will, and just bring in the parts and pieces together to function at like the most efficient and optimal level. You can say you need a smooth wing surface for the best performance, but it’s in how you design it, and like, also the look, because that’s another thing you have to keep in mind with these cars, too, is like, if it’s functional, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to go fast, like, there’s this whole fan base anyway, like, there’s a balance of where engineering still needs to go.

Be [00:40:00] functional and appealing.

Crew Chief Eric: So to take it back to aerospace, it’s sort of like the Concorde. It looks fast, even when it’s not moving. And it is fast, ballistically quick.

Lauren Sullivan: Yes, it is. Yes. Yeah, it looks and, you know, cause like you see an IndyCar and you’re like, that car goes fast. You don’t see an IndyCar and think, Oh man, I bet, you know, that’s just someone’s daily driver.

Like it’s how it looks. And then it’s backed up with the data.

Lauren Goodman: No one’s like, I’m going to use that to go get groceries. No,

Lauren Sullivan: no, no, no. And it’s, you know, you know, it’s an art form because it’s what a lot of consumer cars will kind of try to bring in elements of that to have that same draw or to have that same feeling they play on the art form of.

the cars that go fast.

Lauren Goodman: If engineering is about thinking outside the box and approaching a problem from a new angle, is there an example, either from NASCAR or Open Wheel, where you can illustrate this? Because a lot of people don’t think that engineers are creative.

Lauren Sullivan: Yes, I see this. And actually I have two [00:41:00] examples.

I have one from motorsport and one from my aerospace days to show the thinking out of the box. So from motorsport, I have to be careful cause I can’t reveal too much, even though this is like eight years ago now, but one of my first one tunnel tests with Penske, we were testing something on the car that I’m just going to call access doors as just an access door for right now.

And we were doing what’s called flow biz, where you put a colored liquid, usually it’s an oil all over the car. Then you turn on the wind tunnel, let it do its thing, and you’ll see the flow structure on the car. And so we did that with these access doors. I asked the question of like, okay, so now that I understand the flow structure, like what does the rule book say on these, on these access doors?

And they’re like, they just have to be there because when you have to access this point on the car, sometimes I’m like, okay. So they just have to be in these certain panels. Yeah, they just have to be in these certain panels. So I go, what if we move these doors and we could still access what we need to, but they aren’t in this spot, but they’re in a different spot.

They’re like, there’s no rule against it. I’m like, well, let’s move them. And we move them and it produced a generous amount of downforce. Fast forward about three years. Now there’s [00:42:00] a rule against it. They have to be at exactly this location. They have to be exactly this size. You have this rule book in motorsport.

I kind of liken it to a toddler who’s always like, but why? But why? But why? They go down that like list of questions. And so like as an engineer, sometimes you’re like, yeah, but, but does it say this? But what about this? But what about this? Like, it says this, but doesn’t say this. And back to even my mom instilling in me, never take no for an answer.

Like, okay, you said we have to have these, but you didn’t say they had to be here. Like that happens all the time. If you have a rule book, out of the box thinking is what’s winning races because everyone has to abide by the same rules. It’s just playing in the margins.

Crew Chief Eric: How you interpret them.

Lauren Goodman: I’m from a family of attorneys.

I fully respect this. It is looking for, where is the margin? I’m not breaking the rule.

Lauren Sullivan: I’m

Lauren Goodman: not breaking the rule. I’m just bending the definition. And if the scrutineer can’t nail me for it, then it’s legal. And I can use it. That kind of

Lauren Sullivan: stuff is going on all the time. My other example that comes from aerospace and this I see in motorsport a [00:43:00] lot as well, but this is a very applicable one to share.

I guess it paints the picture perfectly of what I see all the time in motorsport and engineering in general is really where something that was designed for a different purpose ends up having a purpose within engineering and motorsport purely because of a conversation somebody had or somebody’s hobby or something.

I was like, Hey, I use this. And this, and it could probably fix this problem over here. My example from aerospace is in wind tunnel testing, specifically in high speed, I’m talking like above the speed of sound, high mox, almost hypersonic testing. There’s a problem where you have your model outfitted with pressure tubes that’s running down the mounting hardware that’s in the tunnel.

And so it’s exposed to the flow and you need to protect it. Otherwise, like as soon as you turn the tunnel on, it’s just going to rip those pressure tubes apart. Cause they’re. Very fragile. But those tubes have to go somewhere and go down the mountain hardware because that’s how you get your data. We actually used to protect those when we were doing Mach speeds with the casting material they put on your arm if you break your bone is how we would protect it [00:44:00] because there’s no tape that can withstand Mach 5 without peeling up.

But what they cast your arm with can withstand it. And so we would wrap the mounting hardware with the cast, rub it with water and let it set. And again, that was designed for the medical field, but somebody somewhere, I wasn’t part of that conversation. That was well before my time was like, Hey, we could use this in lint tunnel testing.

Cause it’s easy enough to apply easy enough to remove and can withstand mock speeds.

Lauren Goodman: Isn’t that what’s great about racing?

Lauren Sullivan: Yep. Like that kind of stuff happens all the time. And there’s a lot of stuff we use. Like we use a lot of dental tools sometimes for kicks. Especially when it’s all testing, those are pretty handy to have, if I thought about it longer, there’s many more examples in motorsport, but a lot of that stuff comes to the surface or comes into use because it’s like, Hey, my wife is, you know, a dentist.

And she showed me this the other day. And I was like, Ooh, I can use that at work for this. And that just speaks to collaboration. And again, even if you want to take it back to steam, when engineers are talking with [00:45:00] artists and all that, that’s where these ideas come to life. And these problems get solved by things that already exist.

Crew Chief Eric: A couple of seasons ago, we had Lynn St. James on the show, and she’s at the head of the Women in Motorsports North America, which is an organization that you participate in. So I wanted to get your take on how you’ve seen it grow, its involvement in the motorsports community, the good that it’s doing for ladies in the sport.

And what’s your role in the organization?

Lauren Sullivan: So my role is I am a working group member, which means I’m available for mentorship, um, and outreach and stuff like that. And I do a lot of that through people that reach out to me on LinkedIn and so forth, just looking to connect. One of my priorities with my career is to leave the door open for the generation behind me.

Kind of a cool moment with winning the Indy 500 last year. So as you guys probably know, Caitlin Brown was the over the wall inside front tire changer on Joseph Carr. She is Penske’s first female that to go over the wall. And she is the first female in the history of IndyCar to go over the wall and win the Indy 500.

Huge, [00:46:00] huge moment. While I wasn’t on the two carves specifically for that race, I have a connection with the first female to ever go over the wall in IndyCar. And I was able to call her after the race and just be like, Hey, what you started years ago, I finally just had a female over the wall when the five hundreds.

And her name is Anita Millican. I have a connection to her actually through my husband. He was her tenant when he lived in Indy and worked in IndyCar her phone number still. And she and I connected a couple of times in the past, but for me to be able to be like, knowing Anita’s story and watch Caitlin live out her story was.

Again, a full circle moment where like, Oh my gosh, we’re doing what we said we wanted to do. And this is the progress we want to see. And it’s honestly a short timeline. The fact that, you know, Lynn St. James and Anita are still around to be there as these big milestones are happening. It’s huge. With that role with WMNA, I’ve seen it grow really fast over the last couple of years.

I was able to attend the [00:47:00] summit that was here in Charlotte in 2022. And the summit that was in Phoenix in 2023 was even bigger. And it’s reach is growing even more. The group photos is one thing that’s fun to look at. Cause you can see the group size just grow and grow and grow and grow as more people are being brought into it’s reach.

When it has a presence at a lot of the IndyCar races and then my teammates on our sports car side, they are seeing it a lot at a lot of the sports car races. There’s actually a group of us here in the Charlotte area, a group of us women who get together quarterly. To just hang out, connect, network, and so forth.

It’s kind of like its own Charlotte chapter of WMNA, if you will. And even that with every event we’re adding, Oh man, I want to say like three to five people every quarter. And like now the distros in the fifties or sixties, just for the Charlotte area. And we’ve only done like five or six events. And so to see the momentum this has, as well as it has the support and attention of some big corporations and some big sponsors in the industry that have great initiatives.[00:48:00]

It’s becoming a really good access point for women who want to get into motorsport. When I went to the summit in 2022, one of the things I took away from that was how accessible everybody was. Like I was there in a room and at tables with the CEOs of some companies and stuff like that. And they were just like, yeah, super friendly.

And we got to know each other. And now you have this connection going forward. And there’s even some college girls that came up to me. And a year later, they were emailing me asking me. For some advice and stuff like that. And that’s what it’s all about is creating these pathways for women to find their way into motorsport.

Crew Chief Eric: Some of those CEOs were probably in as much awe of you as you were of them. And it sort of makes me wonder who is like one of the coolest people you talk to at one of the conventions or heard present, who are some of these folks that you’re like, wow, I got to meet that person.

Lauren Sullivan: One of them, and I met her before WMNA, but I’ve gotten to know her more and interact with her more through WMNA is Lynn St.

James. I [00:49:00] met her through Prada Autosport because she was there supporting us and there at the Indy 500. And I remember when I saw her and I was like, Oh my gosh, you know, she was one of the trailblazers for this to happen. This is like seeing it come full circle. This is incredible. She’s probably one of the main ones that has stuck out to me, like getting to interact with routinely through events that WMNA hosts.

Crew Chief Eric: Say you’re at the 2024 WMNA convention or you’re at the next Indianapolis 500 and a little girl walks up to you and says, Lauren, why motorsports? What would you say?

Lauren Sullivan: Motorsport. Because there’s still so much to do. The frontier of it is undefined. There is no limit. I felt like in aerospace, we kind of found the limit to a certain degree in terms of commercial aircraft isn’t evolving very much.

It’s refining itself, but it’s not necessarily evolving and advancing. And same with defense, like the birds, as we call them. Fighter jets I was testing were designed in the sixties [00:50:00] and there aren’t new ones yet because we don’t need to, but it’s just one of those things that you, you kind of found a limit and I feel like in motorsport, we haven’t found these limits yet.

Things just keep evolving on many different fronts, whether it’s the car itself. I mean, even just look at IndyCar rolling out hybrid later this year, things you didn’t think you would see are coming together faster than you were expecting. But there’s still a lot of work to do in motorsport in terms of inclusion and equality and equity.

That limit’s not there. That’s why I choose motorsport. Cause there’s always something new. And like, once you cross one milestone, there’s another one right in front of you. Ironically, there is never a checkered flag.

Lauren Goodman: You’re speaking my language because working at a museum where we have race cars going back to 1903.

That’s been the party line. Racing improves the breed because the finish line is always just over the horizon.

Lauren Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Like it just, as soon as you cross it, it just moves again. It’s always something new and it’s the cutting edge. Cause again, like back to consumer cars, it’s influencing other industries.

It’s finding the new technologies and the new processes and the new ways. I know we already mentioned this earlier, but back to [00:51:00] like the renewable rubber that Firestone’s bringing out, we’re going to see that eventually. On consumer cars, this hybrid system that IndyCar is rolling out. We’re going to see that eventually in consumer cars.

Just being part of that is exciting. And you’re just always chasing the next finish line. I want any young girl out there, any young guy out there who’s hearing, who’s listening to this thinking like I want to get into motorsport and this is something I want to do. We’re knocking down these barriers as fast as we can.

There’s a lot of us holding open the doors as wide as we can for you to come through. And I think you would be surprised if you go to the races and you reach out to any of us of how many of us will stop and chat and make ourselves available because we didn’t have that person growing up. And a lot of the people I work with in Penske and on other teams are willing to share their journey and their path and their network.

So it’s easier for the next generation.

Lauren Goodman: And Sebastian Vettel, he’s taking care of the, um, artificial fuels. Yep.

Crew Chief Eric: Porsche too.

Lauren Goodman: Right, exactly. He’s taking care of that. What’s next for Lauren Sullivan? Oh boy. She’s

Crew Chief Eric: a [00:52:00] Penske. Are we going to see you working on the Porsche 963 anytime soon?

Lauren Sullivan: I don’t know. If I’m going to be honest about that one, I’m going to say I like garage hours.

Uh, what’s next for me? I don’t know. And I, I don’t need to know because I never set out when I was young to be in motorsport and I ended up here. I just take opportunities as they come. When I got into motorsport, IndyCar was never even on my list. And I just took the opportunity as it came. Instead of confining myself to a box, a dream, a goal, I’m just ready for whatever is next.

Crew Chief Eric: Lauren, it’s that part of the episode where I like to invite our guests. to share any shout outs, promotions, or anything else that we haven’t talked about thus far.

Lauren Sullivan: So also talking about the A in steam, there is a balance and they can’t exist independent of each other. And I even find that in myself at work, I’m always doing these highly technical things, but one of my hobbies is big gourmet cakes.

Actually, I don’t do it for money or anything. I just do it for friends, family parties, I go [00:53:00] to, and you can actually follow that on Facebook that has a page that suits my sassy. That’s my creative outlet that I have found that when I look at my life, I don’t know where that skill came from or how it got developed, but it’s the yin and yang I have in a

Crew Chief Eric: motorsport career.

But are they motorsport inspired cakes? Do they look like formula one wheels or IndyCar wheels, you know, Firestone tire?

Lauren Sullivan: No, and the reason is because I’m not good at shapes, but I can do abstract art. It’ll be like a blend of black and red, the Penske colors, but it’s just a round cake.

Crew Chief Eric: Again, the Porsche 963 cake.

Lauren Sullivan: Okay. I mean, yes, this is true. This is true.

Crew Chief Eric: Aerodynamic, right? Put your cake in a wind tunnel.

Lauren Goodman: Yeah, they are aerodynamic, perfectly smooth and delicious. Lauren holds the honor of supporting the first female Ford IndyCar team. Peretta Autosport at the Indianapolis 500 as an engineer, and to quote her directly, quote, everyone is taught the same thing in school.

Therefore, on paper, everyone looks the [00:54:00] same. What you learn outside the classroom is your leverage. And she’s living proof of that. To learn more about Lauren, be sure to log on to womeninmotorsportna. com or connect with her via LinkedIn.

Crew Chief Eric: With that, Lauren, I can’t thank you enough for coming on Brake Fix and sharing your story with us and all the young, inspiring petrolheads that are out there.

And I have to say, that whole expression of no limits. I think summarizes you. You have one of the coolest jobs in motorsport. And what dawned on me is people need to spend more time interacting with the people at the track because you never know who’s walking down the paddock and what job they hold and what their history is.

And we can all learn from each other. And I have to applaud you for what you’re doing and how you’re reaching back to young ladies and young petrol heads that want to get involved. So keep spreading motorsports enthusiasm.

Lauren Sullivan: Well, I will. This has been a great time and thank you very much for the opportunity.

Crew Chief Eric: Officially founded in April of [00:55:00] 2022, Women in Motorsports North America is an official 501c3 not for profit organization. Because of its partners, WMNA is proud of what it’s been able to accomplish. And don’t forget that each year, over 450 women and men from all disciplines of motorsports attend their annual summit.

Attendees are open to industry executives, drivers, team members, OEM sponsors, racetrack representatives, and anyone working in the sport or wanting to learn more about opportunities in motorsport. If you’d like to learn more about women in Motorsports North America, be sure to log on to www.womeninmotorsportsna.com or follow them on social media at Women in Motorsports, NA, on Instagram and Facebook, or at underscore wm NA on Twitter.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at [00:56:00] GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Introduction to BreakFix Podcast

- 00:47 Meet Lauren Sullivan: A Journey in Motorsports

- 01:34 Growing Up in a Racing Family

- 02:23 From Science Fairs to Engineering

- 04:31 Transitioning from Aerospace to Motorsports

- 06:04 Joining Penske and the Female Forward Team

- 07:16 Challenges and Inspirations in a Male-Dominated Field

- 10:27 The Role of Aerodynamics in Racing

- 23:12 Spotting in Motorsports: The Human Element

- 29:17 The Dance of Habit Forming

- 29:23 IndyCar vs NASCAR: An Engineer’s Perspective

- 30:35 The Evolution of Motorsport Engineering

- 31:46 The Reality of Working in Motorsport

- 33:24 Diversity and Inclusion in Motorsport

- 37:11 The Intersection of Art and Science in Motorsport

- 40:42 Creative Problem Solving in Engineering

- 45:05 Women in Motorsports North America

- 49:22 The Future of Motorsport and Personal Reflections

- 52:32 Closing Thoughts and Shout Outs

Learn More

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others by way of Break/Fix and GTM. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

|  |  |

Lauren holds the honor of Supporting the first female-forward IndyCar team, Paretta Autosport, at the Indianapolis 500 as an engineer. And to quote her directly “Everyone is taught the same thing in school; therefore, on paper, everyone looks the same. What you learn outside the classroom is your leverage” and she’s living proof of just that.

There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.

How she got there, Lauren’s Bio — By Jacob Born

1988 – Sullivan is born in Walnut, California.

1998 – Her mom and dad both have ties to racing. One of her notable moments during childhood is meeting racing legend John Force at a National Hot Rod Association race in California.

“Growing up, my family had a NASCAR race on TV every Sunday.”

1999 – Sullivan’s engineering journey begins: she builds a wind tunnel for a science fair project in fifth grade, winning a blue ribbon.

2004 – After her family started a NASCAR super late model racing team in 1999 at Irwindale Speedway, Sullivan joins the pit crew.

2006 – She attends Parks College of Saint Louis University, first majoring in meteorology then physics before deciding on aerospace engineering.

2008 – For a project in her differential equations class, Sullivan builds a “frocket” with classmates, a combination of a rocket and Frisbee. She earns an A in the process.

“That was probably my favorite math class ever. When it came time to make the frocket, I was the only one with shop experience. That was a pretty cool moment, seeing what you’re learning come to life.”

2009 – One of Sullivan’s favorite areas at SLU is the wind tunnel lab. She spends countless hours in the tunnel, both conducting tests and performing maintenance.

“Because I had access to the wind tunnel, I learned stuff faster and was able to hone my skills sooner. It put me in front of people at Boeing who saw what I was doing, and they were impressed.”

2010 – Sullivan graduates from SLU and accepts a job with Boeing, testing fighter aircraft and weapons in wind tunnels.

2015 – Sullivan decides to pursue a career in motorsports, joining Team Penske’s NASCAR team as an engineer. Also this year, after meeting at SLU years ago, she marries Sean Sullivan (PC ’09) in St. Louis.

“In aerospace, I was just always looking forward to the point in my life where I wasn’t going to have to work anymore. Working in motorsports, I, ironically, don’t see a finish line I’m trying to get to. I’m just having fun and taking every opportunity as it comes my way.”

2018 – Supporting NASCAR driver Joey Logano, Sullivan wins her first NASCAR Cup Series Championship. She goes on to win two more championships, one in NASCAR and one in INDYCAR.

2021 – Sullivan is a part of the Paretta Autosport team, in a technical alliance with Team Penske, at the Indianapolis 500, which made history as the crew with the most female members.

“For any females interested in getting into engineering, motorsports, any STEM-related career: Society is changing, and you don’t need to fight for a seat. Just take it. You are wanted here.” — By Jacob Born

To learn more about Lauren be sure to logon to womeninmotorsportsna.com or connect with her via LinkedIn.

There’s more to this story…

Lauren admits one of her guilty pleasures, and a way to decompress after the challenges of being a racing engineer, is to create motorsports inspired… CAKES! You can check out all her delicious creations on her facebook page.

Support Women In Motorsports North America (WIMNA)

Women in Motorsports North America is a community of professionals devoted to supporting opportunities for women across all disciplines of Motorsport by creating an inclusive, resourceful environment to foster mentorship, advocacy, education, and growth, thereby ensuring the continued strength and successful future of our sport.

Guest Co-Host: Lauren Goodman

In case you missed it... be sure to check out the Break/Fix episode with our co-host. |  |  |